Crisis as Crucible: What Do We Really Need to Know?

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

A crisis has a way of making clear what is essential and what is superfluous. What skills are essential, especially for students who face racial and socioeconomic discrimination?

The Workshop School is less than four blocks from 52nd Street in Philadelphia, where protests and police aggression and decades of bigotry, disinvestment, and violence in all its forms mixed and exploded in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. People who stayed home could still feel the tear gas. Those who went out were presumed to be a threat and were treated accordingly. This feels like the only thing that really matters right now, but I’m not ready to write about it yet. I’m still sorting out my thoughts, but more importantly I’m trying to listen and to follow. Apologies if this post feels a bit out of step with the moment.

Optimism is hard to come by right now, yet the present moment is powerfully educative. We are all being tested, in the most authentic sense of the word. A crisis has a way of making clear what is essential and what is superfluous. What do we really need, and what should we leave behind?

My last moment of normal was sitting in a hotel room in New Mexico watching television. I was scheduled to leave for SXSW EDU two days later, but an email popped up in my inbox informing me that the city of Austin had cancelled it. My first thought (embarrassingly in hindsight) was that it was an overreaction. My next thought was that I needed to get back home as soon as possible. A flurry of logistics followed, and then a slower process of figuring out how to get various travel expenses refunded. This required locating and processing new information quickly and sifting out the stuff that was irrelevant.

It was just the beginning. I got back home on a Sunday, and we still had school Monday. An official decision to close would not be made until Friday afternoon, and even then only as a temporary measure. Everyone on our team was reading. We were learning about coronavirus specifically and virus transmission in general. We were getting a crash course in public health and epidemiology. We were watching closely the events unfolding in Wuhan and Italy and Seattle and Oakland. We were talking to each other and sharing articles. None of us could say for sure that we knew what was going to happen, but we knew that sooner or later schools would close. And we knew that like any social, political, or environmental disruption, communities like the one we serve would be hit hardest.

Triage started that Monday afternoon. We began collecting data about who had access to the internet or a computer at home. We began formulating a plan for distributing Chromebooks for home use. We started talking with staff individually and in small groups about what aspects of our work would translate most directly to an online environment—what we could keep and what we would need to drop. By Wednesday, we had a basic framework for the transition. We would prioritize first and foremost staying connected with students. This meant experimenting with approaches to running circles or check-ins and posting frequent, small assignments to encourage regular contact. Staff worked in small groups, often grade teams, to revise projects and deliverables. By the time the closure was announced on Friday, about 210 of our 240 students had a workable technology solution in place. (The remaining 30 would have computers delivered to them the following week.)

The process was messy and chaotic, a tangle of emails, Google docs, Slack postings, and conference calls. The solutions we came up with were far from perfect. But in five days, we shifted from being a school centered around physical space and community to a virtual environment.

Faced with a pandemic unprecedented in our lifetimes and an environment characterized by rapid change, volatility, and no small amount of trauma, what did we really need to be good at?

With the initial sprint over and everyone home and in isolation, many of us began to feel the weight of what was happening. For one thing, we were cut off from our students and each other. (We have all come to appreciate the value of Zoom meetings, but if the energy of your school feels like a Zoom call then there’s something wrong with your school.) We feel the relationships we have with our kids. So much of our work is place-based. So much of our work comes to life in moments of spontaneity or in chance interactions. So much of our staff’s wisdom lies in what they can read and sense that is not said directly. We miss all of that, and while it may be less stressful to work at home every day, it’s also a lot harder to get fired up for it. Most of us were experiencing a sense of loss.

We all coped with this in our own way, but for all of us it required moments of quiet reflection, tuning in to our own feelings and needs, and finding ways to reach out to friends and loved ones. There are a lot of ways to open up, ask for help, or admit that you’re hurting. We made space to do that with each other. Some needed that, others were more reserved.

As the quarantine dragged on, we learned more about what was and was not working. Assigning and grading work every day was not sustainable, so we pivoted to an alternating schedule where teachers had more dedicated time to give feedback. We spread out large group online gatherings and focused more on smaller groups or individual check-ins. We were really concerned about our seniors receiving the support they would need to wrap up the year and transition to college or work, and we needed better ways to coordinate around individual students. So we created a parallel set of tasks related to postsecondary transition that would be supervised by mentors responsible for checking in with students about progress on those tasks. We also built a new database that pulled disparate information from a variety of systems into a single spreadsheet which updated in real time. Staff could post updates on individual students knowing that other key staff would know where to find them.

So let’s review: faced with a pandemic unprecedented in our lifetimes and an environment characterized by rapid change, volatility, and no small amount of trauma, what did we really need to be good at?

- Asking the right questions.

- Assimilating and synthesizing information quickly.

- Collaborating and communicating.

- Being self aware and knowing when we need help.

- Being empathetic and supporting others.

- Reading the environment and adapting as circumstances change.

- Creating and iterating, learning as we go.

Personally, I learned very few of these skills in high school, college, or graduate school. Most people don’t. And yet they are essential, especially for students who face the kind of discrimination that ours do.

Crisis can be clarifying. We know what really matters. We owe it to our students to make sure they have a chance to learn it.

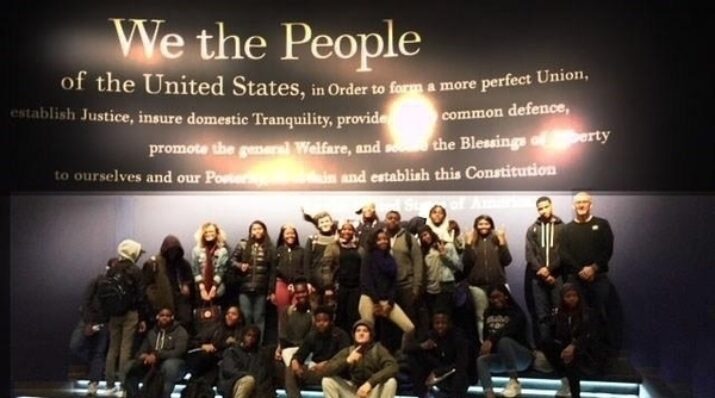

Photo at top courtesy of the Workshop School.