Chicken Run: How Do You Document Process in a Way that Doesn’t Suck the Life Out of Project-Based Learning?

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Instead of asking, “How might students better document their learning?” what if we asked, “How do we help students tell the story of their learning?”

“Do you have astroturf?” That was Gary Chapin’s first question when I introduced this challenge:

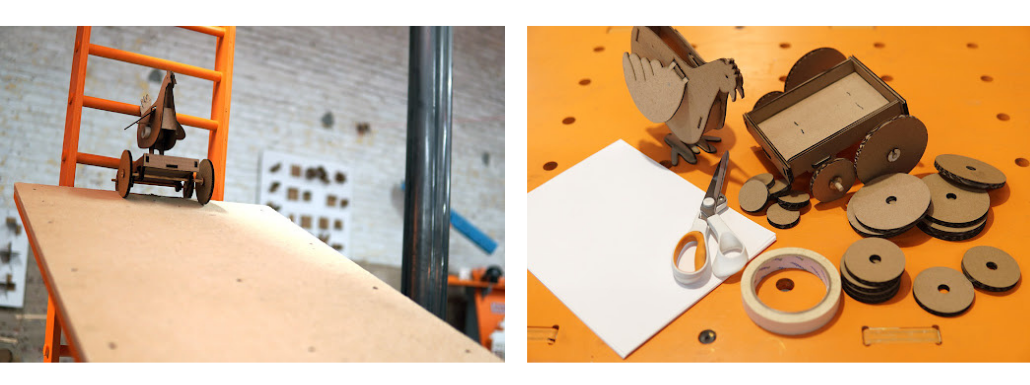

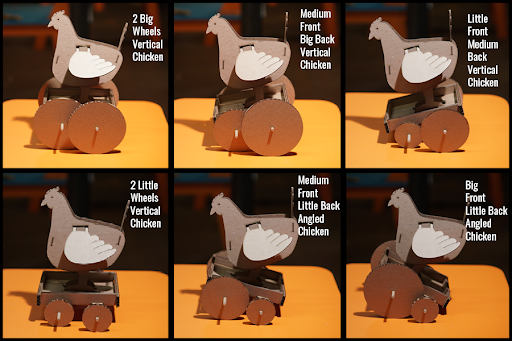

There is a chicken on a car about to roll down a ramp onto a table. You must design a system to keep the chicken in the car and prevent the vehicle from rolling off the table. To solve this challenge, you have the chicken, the car, an assortment of different-sized cardboard wheels, office paper, masking tape, scissors, and one more material of your choice.

When designing projects for students of any age, I insist on constraints: both rules to follow and materials available. Constraints free up creative thinking. They are paint for a blank canvas. What if I introduced the chicken challenge without limiting the materials and then just said, “Go!”? Gary might have felt overwhelmed. With maker projects like this, I assume there are always makers and non-makers in the room. Constraining the materials offers a hint for how to get started without giving away the answer: change the wheels or add some paper. Tools like scissors and tape also offer clues: you might want to cut something or attach something.

I also want to make room for students to select their own resources so I offer, “one more material of your choice.”

Gary asked for… “Astroturf?” It just so happens that we did have some astroturf. (And I knew this would be a fun afternoon.)

I had invited Gary, an author and assessment consultant with Educating for Good in Boston, to our workshop at EXPLO because I wanted his help thinking about how we might better document student work on projects. “Projects” is a broad term. It covers anything from building a robot to putting on a school play. Projects have an outcome—a made thing, a performed thing, or a written thing. When it comes to assessment, we often (too often) base our grading on that made thing. We hang a painting in a gallery and say something like, “You made this? I can’t believe you made this!”

Products are essential. However, project-based learning is such a valuable experience because ideation, critical thinking, collaboration, iteration, and reflection each occur during the process of making. If we only focus on the final product, a misshapen vase we turned on a pottery wheel or a chart that tracks the growth of a pole bean, we miss the how-you-got-to-this-product. That’s where the learning happens. But how do you see it?

Gary had done an EXPLO Elevate webinar for us about ethical assessment where he connected assessment to storytelling. For me, that stuck. Instead of, “How might students better document their learning?” Gary asked a better question, “How do we help students tell the story of their learning?” I wanted to see Gary tell the story of how he saved a cardboard chicken.

Here’s a list of my take-aways from our fowl rescue:

Documentation Is a Buzz Kill.

From our first test, the exercise was an excellent reminder of how easy it is to not document—to not even want to document—when you're in the flow. We started as conscientious scientists. We drafted a chart listing all the variables we might test. By the second or third test, crumpled paper and astroturf were flying, and we had abandoned the chart altogether. There wasn’t time “to write down the results.” Chicken’s lives were at stake! I’m a documentation enthusiast, yet I behaved the way I’ve seen many (much younger) students behave when you stop the action and ask them to write for three minutes about their experience. It’s all groans and eye rolls.

A Picture’s Worth a Thousand...

Without prompting, we pulled out our phones. We wanted to document the work, but we didn’t want to chart it. I took pictures of changes to the chicken car, and Gary narrated a video. This leads to what I learned from the day:

- Let students tell their stories their way. If the students invent a method for documenting their progress, it’s 1,000x more likely they will stick with it over the ones we impose on them. That Gary and I abandoned our chart is not a condemnation of charts. In fact, a well-designed chart is a beautiful way to display data and document process, especially for your detail-oriented students. Gary and I were inclined toward images. If students are inclined to write, let them write! If they are graphic designers, let them design a flow chart or layout a timeline. For group work, consider assigning one student as team journalist. That person’s work on the project is to tell the story of their team’s work. At the end of the day, reserve time for your journalists to share their stories. This position is critical to a team’s success particularly if the task goes on for multiple days.

- Default to visuals during the creative, iterative phase. Recording images (moving or still) is quicker and less disruptive than writing. At the end of the project/day/class, students can go back through images and write about what they see in their documentation. Visual records also help us see things we might have missed at the moment, whereas written notes are a reminder of what happened.

- Sneak some scientific method into the storytelling. When designing projects (about saving chickens or otherwise), consider adding a tripod for recording visual documentation and encourage students to record from a consistent vantage point. For your writers, encourage them to use a framework (grid or table) which prompts making similar observations and noting changes from one iteration to the next.

Let Them Use Phones!

Phones offer many methods of documentation that can dramatically impact learning. In addition to photos and standard video, kids might record an audio track, post to Instagram, make a TikTok, access a slide deck, work on a virtual whiteboard… One of my favorite built-in tools is slow-mo video. Things happen pretty fast when you’re rolling chickens in cars down ramps. It’s difficult to assess the impact of a design change in real-time. Here’s an example:

Slo-mo video helped Gary and me witness Newtonian physics frame by frame. Notice how, in this next video, you can see the exact moment (and spot) that dislodges the chicken from its chariot. The documentation was both a record and an observation tool.

A Bonus Take-Away Not about Documentation

Running through the project task with Gary reminded me that things never go as planned (and that's ok). I intended Chicken Run to be about engineering the car to handle the impact of falling off the ramp (and still protect the chicken). I expected we would do all our work on the vehicle. Gary’s instinct out of the gate was to change the ground (asking for astroturf). That was a good reminder of how students always bring outside-the-box ideas, and we need to make room for that in our project design.

Gary invented an approach to the problem I had never anticipated. Rather than say, "You can't do that," I had to take a beat and let go of my expectations. The hardest part of teaching project-based work is not knowing the outcome at the start. Despite decades of effort to avoid simply downloading knowledge from a teacher to a student, too often we still get in the way. It's reasonable that teachers feel uncomfortable setting up a challenge with no known result. And yet, that is everything that happens after and outside of school.

There are three books I carry in my backpack all the time and one of them is Gary’s 126 Falsehoods We Believe About Education (co-authored with Carisa Corrow). It’s the kind of book you can (and should) pull out anytime and open to any page. I bet that page will connect to whatever you’re doing. Right now I’m flipping to page… 41. “Falsehood: Kids know something only if they can work with it in words.” See what I mean?

Our most compelling documentation from Chicken Run wasn’t our chart or this write-up; it’s the videos where you see creativity, collaboration, and trial-and-error in action. You can also track our emotional highs and lows. (It took us 18 attempts, four hours, and a sushi break to get our chicken safely down the ramp and onto the table.) Here’s a recreation of our successful run:

Watch the vehicle’s remarkable recovery after an initial disruption. It’s a good reminder: always wear your seatbelt. Videos like this are a great way to see and study the event. However, the take-a-way is not “always use video.” What makes our documentation compelling is that we wanted to record it and chose our way to tell the story.

For another perspective on this project-based learning task, check out Gary’s story of saving the chickens.

READ "THIS IS ME, LEARNING ABOUT HOW I LEARN"

Photos courtesy of the author.