Failure This School Year Is Inevitable. Now What?

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

Educators have an impossible challenge ahead of them this year, and they are courageously working to get it as right as possible.

Get ready, fellow educators, for a big dose of failure. Accept it: your school is NOT going to succeed this fall, at least not in many of the ways that you have measured success in the past, and not in the eyes of many of your stakeholders. Our bar has always been high: preparing each child to succeed in their future, even as our society has loaded us with more responsibilities, and often with fewer resources. Rising to that bar this year, I argue, is an impossible challenge. Yet, while failure is your likely destiny for a good part of the coming school year, you do have an opportunity to fail forward. In the past schools have not been organized to fail forward. An “F” often stays on a report card forever, and no teacher wants to be known as the one who has “failed” her students.

So, why is failure a certainty this year, and what might you do about it?

Like many education networks and consultants, Springpoint Schools just published their guide, “Maximizing Student Engagement and Learning: A Guide to High School Planning During COVID-19.” It is a comprehensive and valuable checklist of what schools need to do to succeed in their core mission of student learning in this time of pandemic. I encourage school leaders to add it to their toolkit. That is the good news.

The bad news is that there is not a school on the planet that will come close to making a passing grade on all of the items in this guide. Like the lofty expectations often listed in a job posting for a new chief executive officer, this guide is something that (with no irreverence intended) would be beyond the reach of “God on a good day.” The guide, like many others that you will see as we have collectively digested some of the lessons from last spring, addresses issues across the entire school “operating system:” pedagogy, curriculum, assessment, uses of time and space, communications, equity, leadership, community engagement, technology, professional development, and more. Many of the dozens of probing recommendations in the guide would have each taken the typical school a year or more to tackle, at least way back six months ago when we still thought that changing schools was like re-directing an aircraft carrier.

We know now that we CAN make major changes quickly, but we simply don’t have the bandwidth to make all of the needed changes at once, and equally well. Much of what we learned in the spring shutdowns exposed timeless weaknesses in our K-12 operating system, a list of “deferred maintenance” across a system that has not been upgraded for the better part of 150 years. The Springpoint guide points to many of these, for example:

- Are assessments authentic and focused on topics that are meaningful to students?

- Do students have opportunities to self-assess?

- Do students understand how they are being graded?

- Have teachers been clear about revising what skills need to be demonstrated and what requirements are?

Schools have been struggling to answer questions like these for years or decades, and it is unlikely that the added pressure of widespread virtual learning will suddenly lead to system-wide solutions.

Many really good teachers and administrators I have spoken with in the last couple of months are either on the verge of, or past, broken. Some have not had a day off all summer. Others still don’t know, two weeks before the start of school, whether to prepare for virtual or in-place learning. Others have had almost no support from their site or district leadership. Some have just quit. Many are hearing blame slung at them from vocal parents just because they value their own health and that of their families. All are staring at some degree of failure that they would never have accepted in the past. The combination of burnout and unrealistic expectations is an enormous weight. In the best of times, our school communities are not capable of changing everything all at once; no organization is. That is not how good organizations work. And this is hardly the best of times.

So, what shall we do? Here are a few suggestions to fail forward. None will lead to success in the ways we are used to, but they may help during what is going to be a very difficult fall:

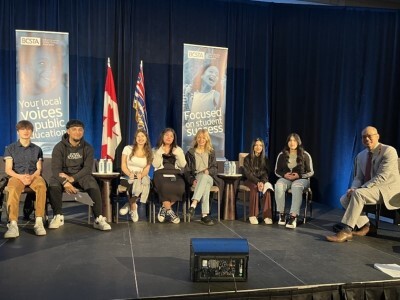

Accept failure right now. Failure is one step in getting better, and failing quickly and making adjustments is the sign of a successful organization. Set up the “war room.” Make sure it is staffed with diverse stakeholders (including students), and not just people with big titles. Pick people who are respected by their peers; not afraid to admit a mistake; able to think creatively, quickly; and give this team a lot of authority.

Dump rigidity and embrace flexibility. You are fighting against a viral enemy, and a key maxim of battle is that plans never survive the moment the bullets start to fly. In the words of one wise edu-leader last week, “school openings are going to be a hot mess; 80 percent of all the great planning we did over the summer is probably going to be thrown out in the first few days or weeks.”

Make choices, even if they might be the wrong choice, and you might have to make a different choice tomorrow or next week. In a rapidly changing environment, a bad choice might not be good, but standing still is almost always fatal.

Do what is best for the long-term physical and emotional health of your students, teachers, and families. School may not be perfect, or even great, but never abandon this core value. The pandemic won’t last forever. There will be some negative long-term consequences of this war. Your job is to minimize those consequences as best you can. Health is a more important consequence than content learning.

Many, perhaps most, of the rubrics that have been used to measure you and your school in the past are no longer the right measurement tools. Educators are going to be hounded and second-guessed by everyone who thinks they know what is best, most with little real evidence of what “best” even means. Emotions have rarely been at this high a pitch in the U.S., and it is likely that, with the institution of education impacting so many families, those emotions are about to become even more divisive and strained. We have devolved to the point where a shared value like learning, and even basic social courtesies like wearing a mask, have become political, and even moral, flashpoints. It has somehow become a fixture that people with no background in epidemiology think they know more about viral transmission than scientists, and people with no professional background in education think they know what is best for long-term childhood development.

My answer to all of those who think they are right is this: There is no "right" answer to school opening this fall. Educators are doing their damndest to get it as right as possible given an impossible combination of circumstance, even though they know they probably won’t. That is called courage.