Interest Driven Assessment Practices that Lead to Personal and Unique Performances by Learners

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Student interest is a motivator and personalization increases access, but how can educators find time and energy to personalize opportunities for assessment?

At Del Lago Academy, part of the Escondido Union High School District in San Diego County, we believe that learning is not bound by the walls of our school. Rich and transformative learning experiences happen at home, in the community, and at places of work. Our internship program allows scholars to leave campus and build relationships with mentors that help shape their identity and learn about the work that happens in our region. For six weeks each spring, junior scholars spend two days a week building skills and knowledge in places of work, such as laboratories, catering businesses, hospitals, and departments within our city government.

Courtesy of Carissa Duran

A Lesson Learned from My Student

A former 11th grade teacher, I also wore the title internship advisor during those sacred six weeks. Advisors have the responsibility of visiting their scholars at their internship locations and checking-in on the progress of their internship by observing the scholar-intern at work and discussing their progress and goals as well as speaking with their internship mentor. During one such visit, brain matter exploded from my ears because a scholar of mine was hard at work, meticulously deconstructing a classic 1960s Mustang which had been in an accident and was in need of reconstruction. My first check-in question was, of course, “What are you doing today? Tell me about it.” The answer was obvious but that’s how conversations go, and we were off.

Mateo (a pseudonym) explained every little detail of the situation—how the car had been in an accident, what damage it caused, and how he had spent hours researching each part it needed to be restored to its original condition, down to the bolts, which at the time he was counting to ensure that as many original parts as possible were preserved. He’d written up recommendations for his mentor who was so impressed with his detail-oriented research and proposal that he gave Mateo free reign over the work.

I was perplexed; this was an entirely different scholar than the one I knew in class. This scholar faced a problem and researched solutions, worked independently, and took initiative when confronted with a challenge. My scholar, the Mateo I knew in my humanities class, he didn’t sustain research more than five minutes, especially not if you weren’t standing right next to him. He wrote when he was directly supervised, but never finished an assignment. He was withdrawn and didn’t answer questions or contribute to solving challenges. Yet, here he was, showing so much tenacity and perseverance in the face of this challenge that he asked his own questions and then sought and found answers, even willingly bringing his work to his mentor to seek validation.

I was doing something wrong.

In that short visit, it became overwhelmingly clear to me that I was not bringing out the best in this particular scholar. This wasn’t a realization I came to years later; in that moment I knew I was not providing him the circumstances to be as successful as he could be. I asked him directly why he was so easily able to conduct research and solve problems here but not at school. His answer was simple and obvious: “I like cars.” I had to laugh. My next reaction was more intentional, though: I told him,

“Choose any of the competencies you still need to pass for my class and we’ll re-write the prompts so they’re about cars or whatever else you’re interested in!”

“Really?!” he said, “I can do that?!!”

“As long as you meet the standards, I don’t care what you write about.”

My conversations with scholars about assessment were never the same after that. I was committed to making my assessments flexible enough to make both the small and big shifts necessary to engage scholars in the work. It’s no secret that student interest, or relevance, is an important motivator and predictor of engagement. It’s also widely known that personalization, or tailoring learning to each students’ strengths, needs, and interests, increases access and student achievement. Still, it can be difficult in the day-to-day work of educators to find the time and energy to build and sustain highly personalized opportunities for learning and assessment.

Putting Personalized Assessment into Practice

Del Lago Academy is highly innovative and strives to reach scholars where they are, meeting not only academic needs but social-emotional needs as well. Our scholars tend to feel safe and supported on campus—Mateo felt safe and supported—yet it wasn’t until he was given an opportunity to put his existing knowledge and skills to the test in an interest-based internship that his potential began to be tapped. At most schools, though, internships are just a piece of the learning. Eventually, Mateo was going to return to my class and he was going to have to show competency on grade-level standards to earn a passing grade. What could I do, six months into the year, to affect change for the scholars I had now? A curriculum overhaul would take a year.

For one thing, I began to say “no” a lot. When a scholar who had not earned a passing grade on their competency asked if they had to retake that same competency, I said no. When they asked if this particular assessment was the only way they could pass the class, I said no. I took a deep look into my assessment practices: I analyzed the prompts I was assigning scholars to ensure that these prompts asked scholars to meet grade-level standards and not simply comply with some arbitrary writing task. Then, I taught them how to do the same. We spent time reviewing the elements of assessment, for their benefit and my own: an assessment will measure content and skills. The shift came when I told them that the skills—those are required—but the content—that could be replaced with something they are interested in. A standards-based assessment should be flexible enough to rewrite with any other content—an argument about public health can easily be an argument about animal cruelty in the makeup industry. A research paper on a medical case study can be a research paper on just about anything else. I continued to teach and assess my existing curriculum, but I allowed for the possibility of modifying my assessments on the fly to ensure I was meeting my scholars where they were.

Without a fully developed system for personalizing learning to match learners’ interests, many teachers shy away from the idea altogether. And it makes sense; it would be incredibly difficult to write 36 different assessments for each unit of study without systematic support or the adoption of a fully developed personalized learning pathway. An easier shift is being willing to listen to the student voice when your existing curriculum is not connecting with them. When a scholar advocates for a modification, it may start off sounding like a complaint. “Do I have to write this?” Your response determines whether or not that complaint becomes an opportunity to incorporate student voice, independence, and self-advocacy. Try saying no: “No, you don’t have to write this. What else could you write to show these same skills?” Start a conversation. Spark their interest. Elevate their voice and their metacognition by engaging them in the task of deconstructing your prompt to identify the standards-based skills it measures and then task them with developing their own prompt to measure their learning. These conversations may not happen with every scholar. They ought to happen with the scholars that your curriculum didn’t grip.

It’s a shift, for sure. But if I am an educator in pursuit of educational justice and equity for all my scholars, I have to also be an educator committed to meeting my scholars where they are. And they don’t have the luxury of waiting for the next curriculum adoption. I have to be responsive now.

One thing I can tell you is that most scholars with whom I had this conversation came back the next day with a page full of notes and scribbled-out half-prompts and more questions than answers. Then, with a few minutes of prompting and reflecting on their thinking, we had a new prompt modified just for them. They had the same testing conditions as everyone else. I used my same rubric for grading, because my rubric was standards-aligned and not compliance-based. It was a small shift with a big impact. It required almost no extra planning on my part aside from one class review on deconstructing prompts to identify the content/skills it measures, which is a lesson that we know should be taught anyway.

I work in a school committed to meeting scholars where they are, but we don’t have a choose-your-own-adventure type personalized learning pathway. Instead, educators are tasked with personalizing and differentiating on our own. By listening to the student voice, even when that voice starts off sounding like a complaint, educators in a supportive school environment can look behind the complaint and see what their students are really asking for—they’re asking to be engaged and we engage our scholars when we take the time to know them and let them show their understanding in ways that are designed just for them.

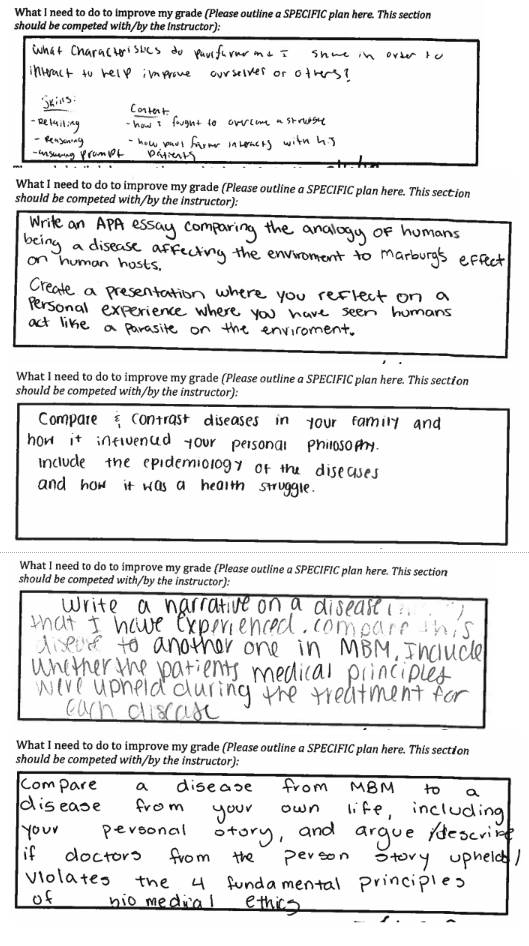

These are samples of prompts that scholars have written on the same topic/unit of study, in many cases choosing to integrate personal stories instead of using published literature: