Magnolia Montessori For All: A Hybrid Model That Asks Big Questions

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

This school displays the aspirational “dream big” type of innovation that is at the core of NGLC's work.

In education, our work lives and family lives often intersect. As the parent of three young children ages five and under, I sometimes feel like I’m running an educational laboratory in my own backyard. When I visit schools, I think about how my own children might experience the environments I see.

I recently had such a personal reflection during an NGLC site visit to Magnolia Montessori For All (MFA) in Austin, Texas, a first-year school serving preschoolers (ages 3-5) and elementary students (grades 1-3). The school’s 300 students come from all walks of life and represent a true mixture of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds.

A Blended School Model

What makes the school particularly noteworthy is that founder Sara Cotner has intentionally blended the best of the “No Excuses” charter school world with the best of the Montessori model. Usually these two models do not overlap in terms of the students they serve or the curriculum and academic model they adopt. “No Excuses” charter schools traditionally serve high-poverty students and involve a fairly standardized curricular model with direct instruction, data analysis and progress monitoring, and a school-wide focus on proficiency in ELA and math. Montessori models have historically thrived in more affluent communities where teachers might assume a certain level of basic skills in literacy and numeracy. Instead of a focus on basic skills, most Montessori models emphasize building students’ ability to direct their own instruction, learn how to be self-accountable, and work independently at their own speed and own pace.

While still in its first year, Cotner’s school represents a truly innovative model (and I don’t use that word lightly). It is currently the only public Montessori school in Austin and one of the few Montessori schools in the country serving a diverse student population and providing a rigorous Montessori education for free.

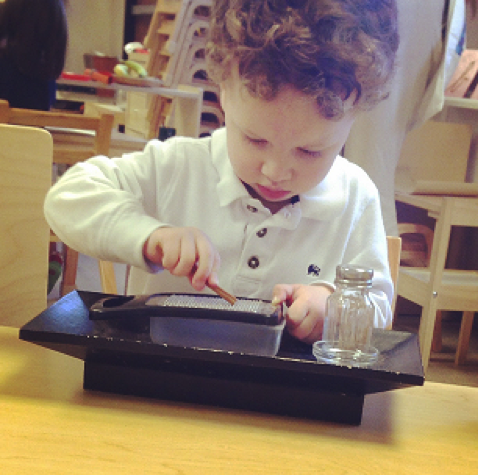

As I visited MFA’s portable classrooms, serenely furnished with neutral-colored IKEA furniture, I imagined my own three-year-old grating carrots or my five-year-old using the Montessori beads. The school was a magnificent display of the aspirational “dream big” type of innovation that is at the core of our NGLC work.

Sitting in the tranquil classrooms gave me plenty of time to think and wonder. So here are three questions that emerged from spending time at MFA. These questions are meant to be answered by YOU.

1. Are smaller classes more important in schools where students have more agency?

In a “No Excuses” charter school, a larger class size might be more feasible because students are, for the most part, working on similar curricula. With direct instruction, it is easier to hold a larger group of students accountable and ensure that no one falls through the cracks.

Yet as the academic model becomes more differentiated, and involves greater levels of student agency, larger class sizes make it harder to meet everyone’s needs. Managing and monitoring 20 different learning plans is much more doable than managing 30 plans. The Tennessee STAR experiments—one of the most well-regarded education research studies on class size--were conducted in an era before competency-based or “next gen” learning models and did not directly address the impact of academic model on class size. Perhaps the next round of class size studies should investigate the effects of class size in more personalized environments.

Education writer Sam Chaltain has discussed Maria Montessori’s preference for larger class sizes because additional students allow for flexible student grouping. See Chaltain’s thoughtful piece, which adds to the important conversation on what our next generation of classrooms should look like.

Does class size matter in a personalized, choice-based setting? Tell us what you think!

"I definitely think there are children who struggle to learn how to handle freedom with responsibility, but, ultimately, they have to learn it because that's what life is: freedom with responsibility"

–Sara Cotner

2. Do school models that rely on high levels of student agency and choice require a certain level of prerequisite fluency in basic skills?

One emerging challenge in the first year of MFA is that some experienced Montessori teachers may unconsciously assume a certain level of basic skills that students receive at home (basic phonics, basic numeracy, etc.). In a more diverse school setting, however, the academic model needs to take into account how to fill skill gaps at varying degrees while also upholding the ideas of choice, student agency, and ownership. Not all parents have time at night to read with their children and reinforce literacy.

As parents, we do the best we can to help kids with basic skills, but even the most affluent parents rely on our schools to ultimately be responsible for filling those gaps in our children’s skills. A busy lawyer friend recently complained that her daughter’s school assumed that all students were getting “the basics” at home and, instead, could spend the school day on creative projects and field trips when in fact, the student had big gaps in her reading proficiency.

In environments with extreme personalization and choice, how do teachers also work to ensure a baseline of proficiency in important skills? Tell us what you think!

3. How do school models with high levels of student choice take into account that some students need an additional adult “push” to learn something new?

If you were to build a magical playspace that had every type of toy beautifully displayed, one child might always gravitate towards the little Legos. No matter what. She would work diligently, focusing on building a highly intricate creative ship or castle. Another child, faced with endless possibilities for how to occupy her time, might flutter around trying different options, opening herself up to different experiences, from art to puzzles to building to dramatic play.

Children—even those raised in the same household—have different proclivities in their interests and natural levels of curiosity. In an entirely choice-based environment without too much adult direction, how do we ensure that some children receive that extra push to try new things, broaden their world view of what is possible, and push themselves out of their comfort zones? Perhaps the answer is that not only should our schools differentiate instruction but they should also differentiate the amount of choice provided to children, based on individual need.

When I asked Cotner to explain her rationale for developing a school with such high degrees of choice, she didn’t miss a beat. Here is what she wrote: “I definitely think there are children who struggle to learn how to handle freedom with responsibility, but, ultimately, they have to learn it because that's what life is: freedom with responsibility. That's why I believe in Montessori for all. Montessori is focused on how to teach children how to handle their freedom responsibly. If a child comes in and isn't handling their freedom well, then we take away some of their freedom. But we would always be looking for the opportunity to ignite her passion and her curiosity and her drive. We would always be looking for the right time to wean her off of our adult-controlled supports. Because she's going to have to learn how to be self-directed at some point! My guess is that she's not going to end up in a factory with someone telling her what to do and how to do it at every turn. Traditional school—as you know—is a one-size-fits-all approach. There is no nuanced treatment of children. Montessori is completely differentiated--both academically and behaviorally. If a child needs more structure, we can give them more structure.”

Is it possible to individualize the amount of choice provided to students on a case-by-case basis, according to the amount of self-direction students’ exhibit? Tell us what you think!

Sara Cotner, her phenomenal teachers and staff, and the parents that have believed in her model, are truly inspiring for those us working to redefine the next generation of learning. They are beginning an important and rich conversation that we at NGLC facilitate all over the country each day. If you’re ever in the greater Austin area, I would highly recommend going to see Magnolia Montessori For All. The school embodies the essence of NGLC in terms of its bold vision, its creative hybrid model, and its pursuit of excellence.

I’ll end this post with a hearty congratulations to Magnolia Montessori For All, one of NGLC’s planning and launch grantees; following a school and its leaders through the full cycle of concept to completion is one of the most rewarding parts of my job.