Recruiting Teachers for Personalized, Competency-Based Schools

Topics

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

The success of any school model depends on the people who implement it. One school organization looks at how teachers make decisions when hiring for its personalized, competency-based model.

As we seek solutions for underperforming schools, more and more charter management organizations are going to turn to non-traditional models that, in turn, require non-traditional teachers.

Matchbook Learning's blended learning model, using our Spark platform along with extensive training and support for teachers and a high level of accountability, is an example of that type of approach and our quest for the right educators is ongoing and ever evolving. That's because no matter how data driven the process, it requires a certain amount of judgment about intangible attributes a candidate possesses.

Obviously, schools are not the only type of organizations that have to deal with intangible challenges. We've all had the experience of visiting a restaurant that had a great location, beautiful décor, a top chef and mouth-watering menu, only to feel like there was something not quite right—your needs as a customer not quite satisfied. Still, it's often hard to put your finger on why one establishment works and one doesn't.

The analogy may be a bit of a stretch, but anyone who has hired personnel of any kind—let alone teachers—has had the experience of hiring someone who has great experience, glowing references, a strong positive attitude, and yet—for some intangible reason—doesn't quite live up to expectations. This is crucially important in a school environment because, unlike in a restaurant, if a member of our staff isn't up to the job, the result is not simply a few bad meals—it's a failure in educating children.

In our next charter school, which we hope to launch in Indianapolis, we've been trying to apply some science to this otherwise hard-to-nail-down set of intangibles, as we try to determine what makes for an excellent teacher in our innovative personalized, competency-based model.

Last year, every one of our teachers took the "Judgment Index," which is a research-based scientific assessment (takes about 20 minutes to complete) used by numerous organizations, from the military to Fortune 500 companies to universities. We chose this tool because, rather than evaluating someone's personality or competencies (which are important, but insufficient on their own), it analyzes how people make judgments or decisions.

Next we cross-referenced these judgment profiles to those same teachers' results—quantitative academic data and qualitative observational data. We looked at teachers we hired who were outstanding as well as those we hired who we thought would be outstanding, but in fact, were not. Some patterns began to emerge and suggested some key characteristics we can use in our future selections.

The most important of these were "grit," "curiosity," and "coachability."

1. Grit. There is significant emerging neuro-science linking a person's "grit" to future success in life. But how do you screen for grit?

Consider this example: Two candidates both attended a similarly great university and graduated with similarly strong GPAs and a comparable record of internships and extracurricular activities. One candidate worked three jobs to pay their way through college. The other received scholarships and help from family. There's nothing wrong with the second candidate—they might turn out to be a great teacher. But if all other factors were equivalent, to break the tie, I would choose the first, based on their having already demonstrated grit by working their way through school. This is important in our model, because learning a new way of teaching—personalizing instruction one student at a time—requires learning a new way of doing things that can be hard, unnerving, and challenging. On top of that, we are working with students who come to us with many deficits in their lives. Grit will get someone through the hard parts before it becomes easier.

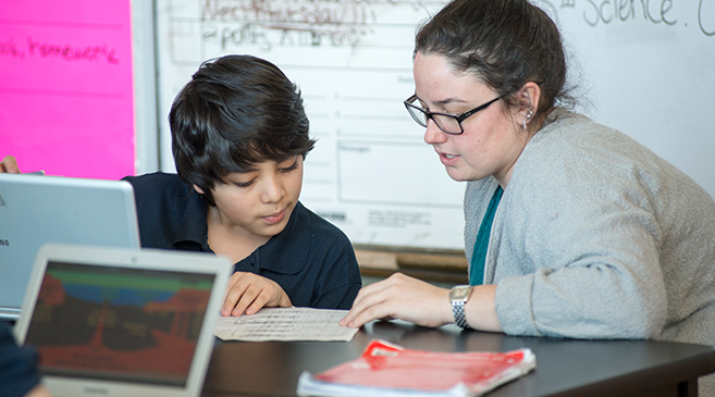

2. Curiosity. There are no magic bullets. There is no singular right way to teach a student how to compose a persuasive essay; no super textbook for learning linear equations; no dominant method for applying critical thinking to conceptual problems. Our teachers have to try different approaches with different students with different learning styles. And when a particular method or approach does not work (which inevitably will be the case), they will need to be curious enough to understand why it did not work, develop a new hypothesis for progressing the student, and testing that hypothesis again. Our teachers must model in their practice the very curiosity we hope to see in our students.

3. Coachability. Personalization not only applies to how children best learn, but also how adults learn best. Meeting every teacher where they are and progressing them toward mastering their craft requires frequent opportunities to observe, diagnose and engage in dialogue on areas of strength, weakness, and possible improvement. It also requires teacher receptivity.

Our approach necessitates one observation a week for every week of the school year, leading to approximately 40 touch points a year for every staff person. Not every teacher would welcome the continuous feedback, especially if they prefer school environments where they can operate as free agents, but the ones performing the best do. We like teachers who can listen, empathize, and work together on a common problem.

We determine teachers' coachability during the interviewing process by frequently asking questions and giving feedback during their live demo lessons. Teachers' reactions and their ability to incorporate feedback into their lessons speaks volumes to their coachability. Additionally, we observe groups of candidates that are gathered for design projects and social mixers to see if they will positively contribute to our team culture based on how they interact with one another.

We are all searching for the best educational model, especially for children in underperforming schools and underserved communities. But we must always remember that any model is dependent on the people who implement it. Great teachers in classrooms—with the tools and support they need to be effective—and the relationships they form with students are the crucial elements in creating successful schools and successful educational outcomes.