Student Voice in Teacher Professional Learning

Topics

Educators are the lead learners in schools. If they are to enable powerful, authentic, deep learning among their students, they need to live that kind of learning and professional culture themselves. When everyone is part of that experiential through-line, that’s when next generation learning thrives.

Teachers can study their content area, child development, and pedagogy, but students are the best "source" to really know if instruction is engaging, relevant, and appropriately challenging.

Recently, I was building a “ballistic catapult” with my son using materials from a toy kit that was intended to teach Newton’s laws. We got stuck at the final step — threading a rubber string through several holes in order to create the tension that could be used to launch his stuffed animals across the room. The manual had a picture, but no clear instructions. After a few failed attempts, I was able to make our model resemble the picture. Soon, small stuffed penguins were flying across the room to our collective delight.

The catapult successfully launched a stuffed penguin! (Courtesy of Young Whan Choi)

When I didn’t know what to do as a classroom teacher, I often wished that I could look at a manual. Stand here, say these words, pass out this worksheet, and voila, students learn. Turns out that constructing a positive learning experience that will work for a diverse group of students is a far more complex task than assembling a toy catapult. There’s no manual with pictures let alone clear, descriptive instructions.

Yes, there are entire fields of academic study focused on the topic of teaching and learning. And yes, teachers should and must read about their content areas, about child development, and about pedagogical practices. But we should also remember that our actual students are the best barometer of whether instruction is engaging, relevant, and appropriately challenging. This is why student voice is an essential design element for teacher professional development.

This past summer, my colleagues in Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) and I designed a five-day project-based learning (PBL) institute for over 100 teachers. Students played an important role in three different ways:

- Setting our vision for the week

- Reflecting on the classroom learning experience

- Giving input on planning effective PBL units

Setting a Vision

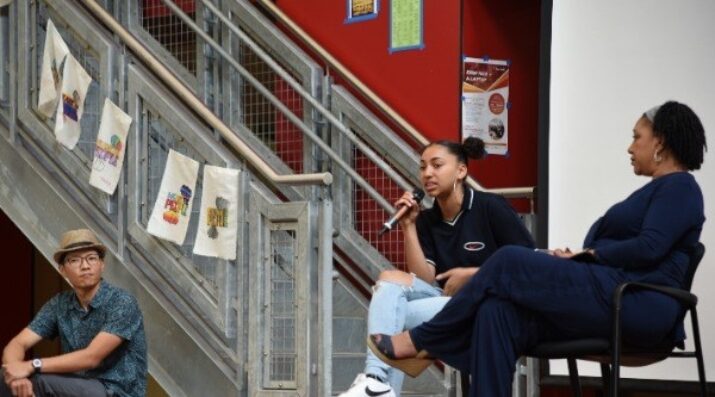

To communicate our vision for the PBL institute, we started with voices from our community to help teachers connect their work in the classroom with the larger issues facing our society. We invited Cat Brooks, a former Oakland mayoral candidate who has been a leader in addressing the housing crisis, and Isha Clarke, climate activist and OUSD high school senior.

At the PBL institute, speaking with climate activist and OUSD high school senior, Isha Clarke, who helped set a vision for connecting classroom learning with larger social issues. (Courtesy of Greg Cluster)

As a member of Youth vs. Apocalypse, Isha has been a leading voice in the Bay Area and nationally for addressing climate change and its impact on working class communities of color. At the PBL institute, Isha expressed to teachers that learning about climate change and working on issues of climate justice was one important way to make learning real and relevant to her generation.

In the daily feedback, one teacher expressed a widely held sentiment, “Both keynote speeches were grounding and gave important insight into why project-based learning in our current cultural context is so important before we dug into the work.” The perspectives of our students are critical in naming what is important to teach; and through their own voices, they deliver the most eloquent arguments, whether it’s for PBL or for other instructional changes.

All students, even if they aren’t nationally recognized activists, can speak to teachers in ways that are more powerful than any peer. After all, teachers enter the profession out of deep desire to serve this next generation.

Reflecting on Their Experiences

Students lived experience in the classroom also constitutes rich expertise that we would do well to listen to. Teaching demands a manner of selflessness. Teachers put hours of work into developing curriculum, but things never go as planned. Students are confused by what teachers thought was clear; tasks intended for fifteen minutes take five. These moments could be endlessly frustrating or seen as invaluable feedback.

When a lesson doesn’t go as planned, which is always, who is there to deliver the message if we are wise enough to listen? The students. Whether it’s a direct comment, “This is boring,” or their attention is directed toward something other than what their teacher is saying, students are providing curricular and instructional feedback. You can’t pay for feedback this authentic and real.

There’s a reason why teachers say that their students teach them more than they teach their students. When we pay attention, and are willing to see the positive and negative reactions of our students as opportunities to learn, students have much to teach us about our teaching.

In this spirit, we also asked a student to speak at the PBL institute about her experience in an integrated PBL unit at Skyline High School. This student spoke to what she learned in the project, how she received feedback, and what it was like to have an interdisciplinary project. Her key point to teachers was that it was powerful to have a single project held across multiple subjects so that she could go deep in her thinking. This message reinforced why we were encouraging collaboration among teams of teachers to build interdisciplinary projects.

A student from Skyline High School offers feedback on her experience with project-based learning. (Courtesy of Greg Cluster)

Giving Input on Planning

I have long considered myself an advocate for student voice. Yet, as a teacher, I often failed to engage students in the planning stages of curriculum. It was fine and good to ask students to share feedback after a unit, but I saw planning as my domain. I have learned from other PD facilitators who have encouraged student voice in the early stages of planning to help shape curricula before it enters the lives of students.

Later in the week-long institute, we invited planning teams to invite a student to join them for a critique and revision session. Students were paid for their time and valued as consultants. They were given time during the PD to sit down with teachers and listen to curriculum pitches. Teachers produced a small slide deck with information such as the essential question, the authentic product students would produce, and some of the key learning activities. Students provided feedback on what they thought would engage them and their peers. One teacher reflected, “It was also very helpful to have student input. Thank you for making sure that the students got paid.”

Teaching is complicated and nuanced because we as humans are complicated and nuanced. To teach well or to support teachers well requires us to steer through the rapids, channels, and waves of human relationships. One day the water may be turbulent; the next day it’s calm. An experienced navigator knows when to set down the manual and look instead at the signs in the water. As teachers or as those who support teachers, students can be our most valuable signposts. As we learn to listen and incorporate their hopes, reflections, and feedback, we become more adept at staying afloat in the topsy, turvy waters of education.

Photo at top: Isha Clarke, climate activist and OUSD high school senior, and Cat Brooks, a former Oakland mayoral candidate who has been a leader in addressing the housing crisis in the city, at the PBL Institute. (Courtesy of Greg Cluster)