“We Do It for the Outcome…” Lies Teachers Tell Themselves

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

How gaslighting, character assassination, and a pandemic have affected teacher retention and pay in the United States.

In reality, it’s one of the longest-running grifts in the nation: “I don’t teach for the income, I teach for the outcome.” You’ve probably seen this dictum smeared across a flowery background, circulating through social media posts. It sounds altruistic and emotionally evokes the reputed image of the U.S. teacher who gives and gives to make all possible for all students. The folly or through line of the story we internalize and believe: educators work for the good of the community, not payment.

Integrity as an educator and in education lies in the perpetuation of this myth. Thus, teachers who ask to be compensated for their time, work, efforts, and output are deviants—penurious, lazy, ungrateful. And with this staunch and supported lens, a long con of overworking and underpaying educators has survived, even during a pandemic.

Teachers work an average of 42.2 hours a week in accordance with their agreed upon contract, but if we count outside hours including lesson prep/planning, grading, professional development, email and/or other communication, teachers really work an average of approximately 62 hours per week, 2,200 hours a year.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the 2019-20 average pay for teachers who are contracted for 180 school days or 39 weeks is around $63,645 per year, about $1,632 per week (or $1,224 on a 52-week payment contract) before deductions, $38.67 hourly. However, if we recalculate this sum over the approximated 62 work hours per week, the impact take home pay for time worked before deductions is a paltry $26.32 hourly on a 39 week pay contract. Still, a number of points are negated, most importantly that the “average” salary isn’t reflective of the populace as some teachers are making significantly less than the average.

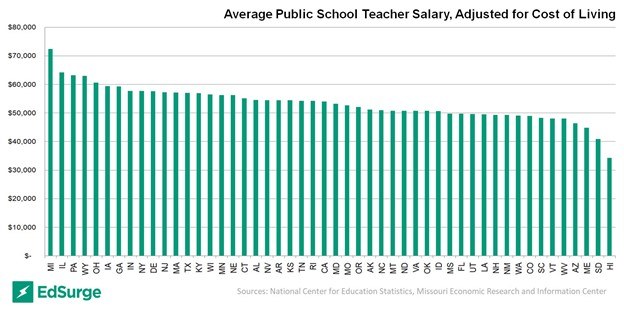

Teacher pay fluctuates by geography and doesn’t often account for the cost of living. When EdSurge used raw 2015-16 data from NCES and adjusted teacher pay for the cost of living throughout the U.S., only four states averaged above $60,000 per year after cost of living adjustments. In a 2020 report, USA Today noted, “The U.S. median annual salary across K-12 teaching professions is $64,524, but it varies significantly by state from just under $45,000 to more than $85,000." Additionally, when factoring in the cost of living impact, even the highest salaries barely factor toward base-level livable wages: “The District of Columbia and New Jersey are the only states with starting teacher salaries over $50,000, with $55,209 and $51,443. Unfortunately, the livable wage is $68,000 in D.C. and $56,000 in New Jersey. Thirty-four U.S. states have starting teacher salaries below $40,000 a year.”

Compounding the disparity in pay is that educators have no access to bill for hours worked after contract time. Recently, Kyle Cohen made national news highlighting the distorted reality concerning teachers’ salaries, revealing his $31,000 salary as a first-year teacher was not only less than half the national average, but when refactored against an estimated 2,160 hours of work, equaled $14 dollars an hour before deductions. Club sponsorship, help at sporting events, school plays, awards ceremonies, chaperoning dances—the list is endless and, on average, adds a minimum of 13 hours of unpaid time per week. Broken down hourly, educators miss out on about $502.71 worth of billable overtime per school week if we use the NCES national average of teacher pay in 2019-20. That’s just over $20,000 per contract year at minimum. Also, when teachers miss a pay step or pay steps are frozen, they don’t get back pay to make that up. What seems like an unimpactful few thousand less per year becomes a glaring issue over 30 years of work: A colleague of mine estimates she will retire with around $250,000 less than planned because of budget cuts and lack of step-increase raises.

As skilled and degreed educators, the cost-benefit analysis of our career is an embarrassing negative. A 2018 article by Time Magazine outlines the fiscal and physical tolls this con has had on our occupation. Educators in parts of the U.S. have to work 3-4 extra jobs just to meet basic needs such as child care, mortgage, and rent, not to mention paying back school loans. In addition to managing life responsibilities on salaries that, in some areas, barely tiptoe outside the poverty pay scale, teachers are expected to yield to the pressure of embracing poverty as part of their image. In an article for Bored Teachers, Rachel Moshman offers further explanation, “Teacher pay is notoriously low compared to other professions that require college degrees and multiple certifications. Teachers are frequently made to feel guilty for wanting more pay since they’re doing the job ‘for the children.’” Educators as a whole have allowed this gaslighting to develop into exacerbated proportions, with superficial peer pressure and a deeply toxic and perversely distorted social media image further distancing us from achieving proper compensation for our work.

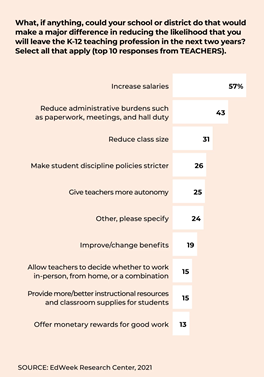

EdWeek Research Center, 2021

During this pandemic, the inequities in teacher pay and work have been highlighted with 75 percent of teachers working 45+ hours a week. As of March 2021, “42% of teachers declared they have considered leaving or retiring from their current position.” If you scroll through social media feeds, you can see daily videos posted by teachers who are leaving or have left the classroom in September, October, and November. No one who wants to stay in education would consider doing something like that unless they have truly decided they are not going back.

In an October article, The Guardian outlined several of the most critical issues teachers face and what we in this profession already know: we are tired and we are struggling. On top of having their own lives (families, loved ones, etc.) to care for, teachers now have to fill in other positions school districts cannot: “[...] schools around the US are facing food supply shortages, and are having trouble finding enough bus drivers, janitors and other support staff. Many also face shortages of substitute teachers, who are needed now more than ever to cover for teachers who are out sick or quarantined.”

But the unspoken burden continues and is intensified with aggressive parents, angry, trauma-suffered students, and little to no support. From Massachusetts to California, schools are struggling to deal with an unprecedented surge in student violence, in both frequency and type. Day to day, communities of teachers face racial epithets, physical altercations, and recently, even murder. Add to this battles over whether critical race theory (CRT) belongs or even exists in schools, grading policies, and behavior and safety policies, the best option then for many is to leave it all behind.

No quick fixes exist for any issue. We cannot raise teacher pay without funds. We cannot engage and prepare the youth of this country without educators. And we cannot break insidious stereotypes for a profession if it no longer exists. For the sustainability of our profession, to retain the quality of education necessary for generations to come, a new standard must be set: My time, my edified certification and licensing, and my career is valuable on a personal fiscal level. Protect me, value me, and compensate me for my work.

Photo at top by Pixabay.