The Best Way to Reopen Schools This Fall

Topics

Next generation learning is all about everyone in the system—from students through teachers to policymakers—taking charge of their own learning, development, and work. That doesn’t happen by forcing change through mandates and compliance. It happens by creating the environment and the equity of opportunity for everyone in the system to do their best possible work.

There is no “one best way to reopen” that will work for every community, school, teacher, family, and child. Districts should solve their spatial/safety numbers problem by enabling families to choose what will work best for them.

“How can we offer the highest quality learning in the safest way possible to as many of our students as possible?”

I can’t recall which ed leader framed her school district’s essential pandemic-era challenge in this way, this past spring. But to me, it had a refreshing, bracing blend of simplicity, dedication to mission, and proactive problem-solving. Her framing bats away two refrains we were frequently hearing:

We’re waiting for guidance from the state. Fine, if it’s helpful, she’ll use it, but she’s not waiting around for it.

If we can’t provide it to all, we’ll provide it to none. She’s not taking refuge in “equity” to shut down learning; after all, what could be more inequitable than leaving the advantages separating white affluence from Black and Latinx poverty entirely unaddressed? Instead, she’s doing everything she can to build toward equitable opportunity for all of her students during these unprecedented times, and every journey begins with its first steps.

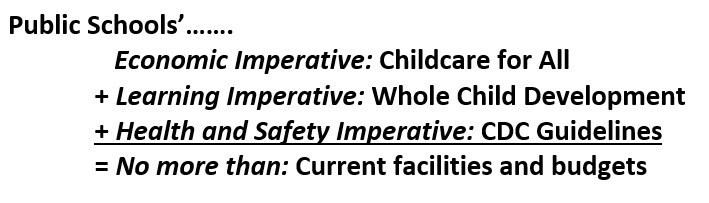

Her question poses the challenge looming before every community in the country right now. Public schools are being charged with solving an impossible logic problem. It’s expressed in the graphic above and the equation below.

This equation won’t add up. It has no solution. Nor does it appear likely that the sum-total “bucket” of facilities and budgets schools are working with will change any time soon—except in a negative direction.

So we have to change the nature of one or more of the three imperatives that make up this challenge. It can’t be health and safety: requiring that teachers and children put themselves at risk, given what we’ve learned about COVID-19’s ability to spread, is policy malpractice bordering on the criminal.

That leaves the other two. A few school districts and support organizations are beginning to show the way. The “best way to reopen,” it turns out, may be to deliberately enable members of the three constituencies directly involved in and affected by public schools—parents, educators, students—to pursue their own “best way,” without leaving the public education system entirely. That flies right in the face of the largely one-size-fits-all approach that most public schools in the U.S. have pursued for nearly a century now. But desperate times call for different methods, and that is where we are.

The percentage of parents choosing all or partial at-home learning will enable schools to work more safely with those choosing all or partial in-school learning. Reciprocal enabling! Let’s call this approach Flexible Choice.

Consider these three constituencies, in order:

Parents and Families

COVID-19, sharpened by expanding awareness of the impacts of systemic racism in the wake of George Floyd’s death under the knee of the Minneapolis Police, has exposed—and exacerbated—the vast inequities in the U.S.’s social fabric. The pandemic has affected everyone, but its impacts on essential workers and those living in poverty and more crowded conditions have been catastrophic. Parents, for many different reasons—economic, job-related, health and safety, their children’s learning trajectory and/or learning needs, or simple cabin fever—are all over the map in terms of their willingness to send their kids back to school.

- Use it. Some districts are seeing this as an asset, not an obstacle. Check out the Miami-Dade County Public Schools’ reopening plan, approved unanimously by the board on July 1. The plan provides parents to choose the best of three options for their children: Schoolhouse (full-time in school), Hybrid (in-school and at-home mix in a couple of different flavors), and My School Online (all distance learning). See slide 36 and after, for details. The Miami-Dade plan is thorough, well-considered, and shaped by input from the community and its own faculty and staff. Providing these options enables parents and students to choose the option that feels best for them. The percentage of parents choosing all or partial at-home learning will enable schools to work more safely with those choosing all or partial in-school learning. Reciprocal enabling! Let’s call this approach Flexible Choice (for which I owe a debt to the Minneapolis design firm Fielding International, which calls it Flexible Return).

Teachers and School Staff

Our nation’s public schools have historically been organized in fairly flat hierarchies that presume similar roles for most teachers. But: Just like students, teachers have different strengths and learning/teaching preferences. Just like parents, teachers have widely varying attitudes about and willingness to return, physically, to school. Some are craving the in-person interaction with students that they lost during building closures this spring; others are more drawn to distance learning, because of safety issues or because this approach has had unexpected appeal—or both.

- Use it. Some districts are seeing this as an opportunity, not a roadblock. Check out Vista Unified School District’s approach to developing its Vista Virtual School and its Fall 2020 Design Plan. Vista re-sorted its teachers and administrators into five “sprint” teams focused on building out pandemic-era approaches to instruction, SEL, nutritional support, health and safety, and technology. Community forums and extensive surveying have solicited parental and student voice. Vista had a head start; the district has worked for years to develop an “all in this together” spirit that puts its mission ahead of individual job descriptions. The district continues to draw on this agility in the face of significant COVID-19 outbreaks this summer in Southern California. What might this look like, elsewhere? In the 2020-21 school year, for example, why couldn’t school districts re-sort teachers into teams that reflect the best matching of school needs (for in-school or remote learning) with teacher need and preference?

Why can’t school districts similarly re-sort teachers into teams that reflect the best matching of school needs (for in-school or remote learning) with teacher need and preference?

Students

Like teachers and parents, students have varying needs and preferences. Some yearn to be physically back in school; others have found latitude, purpose, and direction in learning remotely. They should be part of the decision-making about what might be their own “best way” to participate in school this fall. Schools and districts (and families) that fail to involve students in these fundamental choices aren’t paying attention, either to COVID-19’s impacts on kids’ wellbeing, or to the core principles of learning science. So much of this research points to students’ need for relevance and purpose in the learning they do—and the power of that kind of learning to drive motivation to build core academic skills.

- Use it. Some districts have generated win-wins by enlisting older students as teacher aides for younger students. See this example from Overland Park, Kansas, or the work of Educators Rising, which tracks and supports more than 2,000 future-educator programs nationally. Other schools and districts are involving students deeply in decision-making about—well, almost everything, in the case of Design Tech High School (CA). Those who aren’t listening to students will want to take a look at the work of the Move School Forward alliance, a network of student-activist groups nationwide. From gun violence to social injustice to school and learning redesign, students are showing a readiness to step up in ways that forward-thinking districts can potentially benefit from, in this moment of rethinking traditional roles and habits. (And these experiences, of course, can be life-changing learning opportunities for these apprentice-adults.) This fall, schools will likely need additional hands on deck—even younger ones—to help teachers monitor and support learners in school and (appropriately supervised) online. Meanwhile, high school students are looking for purpose and meaning, while most business-based internship opportunities have vanished. Why is this not a match?

It’s time to stop beating our heads against a wall, trying to force a workable answer to an unsolvable problem. Enabling parents, teachers, and students to choose their own best ways forward, it turns out, might add up to a total far greater than the sum of its parts.

For more guidance and information on district and school reopening strategies, see the NGLC resource base, crowd-sourced from the national NGLC grantee and partner community.

Photo at top by Gustavo Fring.