Where Is the Story? An Illustrated Perspective on Assessment.

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

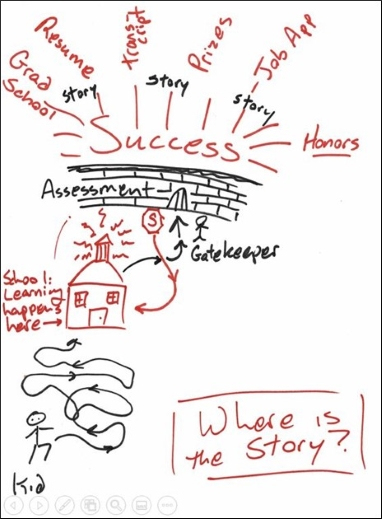

Assessments tell a story. What's the story, and, more importantly, where is the story? The answers to those questions tell you a lot about the values and priorities of our education system and communities.

Assessment tells a story. As much as some might want you to think that assessment is a measure that creates a data point, assessment is a form of research that tells a story. You are researching what your kids know and are able to do and telling the story of their learning. Or, better yet, letting them tell the story. Learning is a complex and intimate phenomenon. Trying to capture the level of someone’s learning with a number is like trying to catch their level of love. It’s absurd on the face, and possibly a plot from Black Mirror. A number is a story, but such a narrow, incomplete, and attenuated story that it is functionally false and practically of no use for the kid.

In addition to the fact that traditional assessment produces stories that are shallow and bereft of genuine insight, there is the problem of where the story is placed.

Two illustrations help (I hope) explain what I mean.

The Traditional, Weaker Assessment Story

The first illustration is a depiction of a traditional, status quo assessment system.

Illustration by Gary Chapin

You can see the kid at the bottom left. They wander around until they get to the school, which is where the learning happens. From there they head to the gate (assessment) and they either make it past the gatekeeper (us) or head back to school. At the age of twenty (in most states) they would be sent off the side of the page toward other options.

But if they make it through the gate that means they have passed the test! Earned the diploma! Huzzah! And that is the only story that’s told. Did they succeed (yes or no, binary) and what was their GPA? Sometimes I think I’m exaggerating when I say that we send kids away for thirteen years so that they can come out with verbal and math SAT scores. But I think I’m only exaggerating a little. To sum up, the story told here is, “Did this kid learn the thing we said they should learn, or not?”

The point is that the story is shallow, and it comes directly after the high stakes event. It’s communicated out into the world through information-poor terms like pass/fail, honors, diploma, summa cum laude, etc. It’s a weak story and, because of where it is in the process, there’s no systematic way for folks to access a better one.

The Ethical, Richer Assessment Story

The second illustration is of a more ethical, richer assessment system. One that is based in context and story, and which recognizes that learning happens everywhere in a community and that learning can be assessed, acknowledged, and certified even if it doesn’t happen within the walls of the institution.

Illustration by Gary Chapin

Here you can see the kid wandering through their community (all the little red stick people) experiencing learning, more learning, and—get this—even more learning. School is a part of that community, an important part, but only a part. All through this process the kid demonstrates their learning, sometimes at formal events, mostly not. And from this collection of demonstrations (a body of evidence) and from the story the kid tells, the community discerns the learning that has happened. As time goes on, the kid (who is all of us) continues to learn and the story continues to develop. This is inevitable. We don’t have to make lifelong learners because humans never stop learning and never stop demonstrating that learning. And in this case the story is always, “What have I learned?”

Photo at top by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC-4.0