Three Ways Music Educators Foster Learning for Life

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Music educators on NAfME's Innovations Council recommend these three practices to promote students' creativity and whole human development.

In recent years, mounting evidence has pointed to the transformative effect of art and music on young people, improving academic, social, and emotional outcomes. For many educators in the NGLC community, the arts play a key role in their whole-human approach to learning, aligned to a definition of student success that embraces creativity, self-expression, and self-direction—skills and dispositions that have long been associated with the arts.

According to Anne Fennell, chair of the Innovations Council of the National Association for Music Education (NAfME), what is less widely known is that education in the arts can also support learners to flourish in a new creative economy. She cites a recent study by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which reports that arts and cultural production contributed $763.6 billion to the U.S. economy in 2015—more than the construction, mining, utilities, insurance, and accommodation and food services industries.

One question that guides Anne’s work as K-12 music program manager for San Diego Unified School District is, “How can we teach with intentionality toward creativity, collaboration, and connection, coupled with excellence in music education, to support students to become involved in or creators of the creative economy?”

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I spoke to Anne and other members of the Innovations Council, educators committed to promoting and expanding innovative pathways in music education for learners in elementary, secondary, and higher education—including future music teachers. The innovative ideas and practices of these music educators align well with many of the broader goals of next gen learning, such as:

- Promoting “whole human” development for lifelong success

- Placing students at the center of their learning

- Providing young people with authentic, real-world experiences

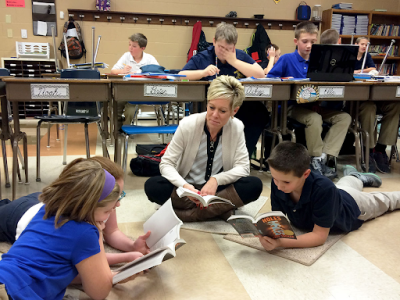

Members of the NAfME Innovations Council (clockwise from top left): Anne M. Fennell (chair), Jamie Stroffolino, Randy Zschaechner, Jarritt Ahmed Sheel, Caron L. Collins, Allyssa Jones, Chuck Hulihan, and David A. Williams

Cultivating the Whole Musician

Innovation means I must continue to learn and grow with my students, and find new ways to embrace, support, and challenge the creative learner with musical experiences that support the whole musician and represent the whole of music.

—Chuck Hulihan, Glendale Community College

One of the central themes of NGLC’s MyWays Student Success Series is designing learning that supports whole human development, learning that gives young people opportunities to develop the full range of capabilities they need to thrive in their future lives. For the educators on the Innovations Council, like many in the NGLC community, that means integrating into their music programs the habits, skills, and mindsets for life.

According to Anne, “Innovation in music education intentionally engages life skills and social-emotional skills with learners’ current and expanding knowledge. Expanding pathways of how students choose to create music prepares them for the next unknown while creating lifelong learners.”

In addition to developing learners’ habits of mind in her music program, Anne emphasizes nurturing learners’ creativity, a key element in what the MyWays Student Success Framework refers to as Creative Know How. “I promote and encourage creativity by inviting the students to create in class every single day. This ranges from composition to arranging and making all decisions within the ensemble,” she explains. “When students engage in creativity, they find ownership of their learning while truly seeing application of numerous skills—from social and emotional skills to music skills and theory.”

Another way to nurture creativity and connect the study of music to developing the whole learner is through interdisciplinary approaches to music education. Chuck Hulihan, for example, integrates music composition and technology in his coursework, like Computer Literacy for Musicians, at Glendale Community College. “Students compose regularly in the computer literacy course, resulting in students creating a portfolio of five or six notated and sequenced compositions in multiple styles,” he explains. “This was an innovative way to upgrade course activities that had previously relied on routine tasks, such as manual music engravement assignments, which involved little to no creative experiences.”

Allyssa Jones, a composer and former program director for performing arts for Boston Public Schools, also points to the benefits of an interdisciplinary approach, telling the story of an experience supporting student literacy in music classes: “Our whole-school professional development focused on supporting adolescent emerging readers and applying strategies in practical ways across content,” she recalls. “The result in my [music] curriculum was a method of decoding and creating meaning in both text and musical patterns. Students became more confident in their learning processes while making stronger, more enduring connections with the music we were making.”

Empowering the Individual As Well As the Ensemble

There is a fine line we all walk when working with our students, of passing down the longstanding tradition of music education, while empowering students to push into a new era of creativity. How can we learn from and appreciate what music has been or is currently, while also saying it’s okay to break those rules and explore new terrain? This is creativity at its uppermost tier, where students are defining these boundaries for themselves through critical thought and identifying what role they play in paving new pathways to the future.

—Jessica Shaw, project manager, University of Saint Francis School of Creative Arts

For decades, school-based music programs have spotlighted ensembles like band, chorus, and orchestra. As the educators in the Innovations Council attest, ensemble performances are still a key part of the music education landscape. However, many have transformed their practice in ways that make learning, creating, and performing music more personalized and student driven. Not to mention more fun!

Today Caron L. Collins chairs the Department of Music education at the Crane School of Music, at State University of New York at Potsdam. She identifies a long-ago experience as a second-year band teacher at an elementary school as the impetus for reimagining the role of the ensemble in music education. After six excellent students quit advanced band, complaining it was “not fun anymore,” Caron recalls her shock at the principal’s response: “Advanced band is not supposed to be fun! You are mature students and have outgrown games.”

That experience prompted Caron to rethink her approach at the time, which she describes as “rehearsals where I drilled the students to perfect selected music literature.” As Caron recounts, “From that moment on, I strove to co-create fun learning experiences with my students, where we were musical partners in the band room. Instead of the traditional director-led ensemble, student musicians and their teacher work together to select a variety of music, create new interpretations, teaching each other through multiple creating-performing-responding activities, and design their performances.”

Learner choice is central to Randy Zschaechner’s approach to the music ensemble as well. As the fifth grade band teacher in Missoula County Public Schools in Montana, he and the beginning orchestra teacher work together to expose learners to a variety of instruments so that they can make a selection based on interest, rather than by the type of ensemble. “Our approach is calculatedly collaborative,” he says, “never once putting one group above another. Our lighthearted and jovial approaches help get the kids excited and guided toward the instrument they’ll be most successful on. Students pick the instrument they are interested in, and we’re off and running.”

David A. Williams, associate professor of music education at the University of South Florida, gives credit for the transformation of his teaching to the K-12 educators—like his wife, a fourth grade teacher—who have been implementing learner-centered approaches for 20 years. “As a profession,” he observes, “we have a lot of catching up to do” when it comes to personalizing learning.

In spite of his modest preamble, David’s current approach reflects a fundamental shift toward learner agency and self-direction: “My classroom is now dominated by learner-centered pedagogical practices that include students working in small collaborative groups, where they have significant autonomy over the musical styles and musical instruments they want to use, as they make creative decisions by song-writing, covering, arranging, composing, and improvising.”

For Jamie Stroffolino, who directs the chorus and orchestra at Walter Panas High School in Cortlandt Manor, New York, personalization involves tapping into each student’s unique and “amazing capability” in a safe and supportive environment. Forging strong relationships with learners is central to his approach: “The simple act of getting to know the values, traditions, morals, and other unique characteristics of all of my students goes a long way toward the promotion of creativity and risk-taking in the classroom. When I believe that students feel comfortable and familial, I ask them to explore creative projects like making a song, learning about their own cultural music history and teaching me or others, and taking songs that are already written and putting their own creative spin on it.”

Allyssa echoes this aspect of student-centered learning in her definition of what innovation in music education means to her: “It is challenging yourself to use program design, repertoire, curriculum, and instructional practices as tools to respond to the lives in the room.”

Jarritt Ahmed Sheel, assistant professor of music education at the Berklee College of Music, also highlights the role of classroom culture in promoting creative risk-taking. He asserts that, “everyone has a creative spark within themselves, and part of my job is fanning that spark into a flame.” Accomplishing that goal, according to Jarritt, requires following his “number one rule” for creating a space conducive to creative freedom: “my classroom—our classroom—is a space of non-judgment.”

In terms of teaching practice, he explains,“I ask a lot of open-ended questions that force you to think outside of the box. I accept non-traditional products as receipts of your understanding—artistic renderings, songs, videos, presentations, poems, graphic novels, etc. that beg the student to really dig deeper than normal. I also try to make a space (time) that allows for imagination, because without adequate time to think of what has never been, no efficient creativity can happen.”

Supporting Real-World Performances

Much of my pedagogy is borrowed from what we know of how popular musicians learn outside the academy.

—David A. Williams, University of South Florida

Performing for an audience has long served as the culminating event of school-based music programs. However, the educators on the Innovations Council describe ways they and innovative colleagues are reimagining student performances and increasing the authenticity of both the processes and products of student learning. In addition to focusing on self-direction, creativity, and collaboration, these music educators prepare learners to engage with the creative economy by designing experiences that replicate the work of professional musicians and connect to the world outside of the classroom.

Caron, for example, shares some “memorable moments” from her practice to illustrate the trend toward authenticity in music education, including “student-created music videos shared on local television, designing their own marching band routines, collaborative music-making with hospital patients and seniors in assisted living centers, connecting via video conferencing on stage with musicians and composers around the world, and now peace-building music activities in local schools. The possibilities of creating musical experiences together are endless, impactful, and ever changing with the times.”

Learners at Walter Panas High School engage in authentic, full-cycle learning by running their own recording studio. According to Jamie, “Panther Records works with our performing ensembles during instruction and concert performances, and guides students who create music and wish to learn more about the recording industry. Panther Records is student run, student centered, and an innovative way for all music students to maximize their music education experience at our high school.”

Anne summarizes the thinking that guides her work with K-12 learners and with the Innovations Council this way: “Innovation in music education is about creating a learning culture that is student centered, where the teacher becomes the facilitator and activator of knowledge to create greater value to the learner. It’s about expanding ensembles, pathways, and programs of study that actively engage students to participate in music as co-creators of their experience and knowledge.”

Resources

- The tools, research reports, and other resources of NGLC’s MyWays project help educators prepare the students of today to thrive in a challenging, unpredictable tomorrow.

- NAfME’s website includes music education resources for educators, parents, and students.

- This report by the National Association of State Arts Agencies provides facts, figures, and links to studies related to the creative economy.

“Personalized Learning Through Project-Based Music,” a NAfME blog post, includes guidelines and practical advice for creating a learner-centered music classroom.

- The Learning Personalized website, a resource recommended by Anne, features the development of Habits of Mind and other life skills for student success.

Photo at top, courtesy of Amanda Avallone: The Steel Drum 2 Ensemble at Mission Vista High School of Vista Unified School District in California.