Kids Don't Like School? Whaaaat?

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Kids don't like school for good reason. The parallel between kids' experiences in school and young adult novels in dystopian settings tells us why.

An eleven-year old friend of ours hung out with my family this past Wednesday. His school is COVID-hybrid, with Wednesday as an at-home day for everyone. A very frustrating day for him, because of tech, uncertain communication, isolation, and rules that seem weird in the home. At one especially tense point, he said, “There shouldn’t be this kind of stress at home! Home should be safe.” Obvious, and profound in his voice. Home should be safe… from school?

Kids don’t like school. Maybe you had forgotten? I was reminded a few days ago when an educator I respect posted the following on twitter:

Until a majority of adults see that children not liking school is actually a problem, we'll likely not make significant growth in the sustainability of educational environments.

— Philip Mott (@PhilipMott1) September 12, 2020

It's not like students are staying silent about their disdain for school; adults just don't care.

There’s a lot to unpack, there—Mott goes on to do just that in the thread—but the thing I want to point out is that the problem he cites isn’t that we don’t see a problem, but that we don’t see it as a problem. The fact that kids don’t like school is as old as Shakespeare, and we seem pretty much fine with it:

And then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. –As You Like It

And, yes, I agree when you say, “It’s more complicated than that.” It is. Kids like coming to see their friends. Different kids like different specific things they do, like art, music, reading, sports, math, science. They like their teachers. We are, as a rule, a pretty likeable group.

But the Project of School (which is different from the Project of Learning), where kids are brought together en masse, expected to learn things they never expressed an interest in learning, are put through a process that is largely indifferent to their concerns and needs, and then are judged (in a “permanent record” kind of way) on the outcomes—the kids are not so into that. Oh, and did I mention that they are placed in competition one against the other, sorted in rank order down to the hundredths place, and then told that their success is entirely up to them, and their failure a reflection only of them. Also, they have to ask permission to go to the bathroom.

John Holt, in his 1964 classic, How Kids Fail, wrote about conversations with some folks in which he mentioned all that. Among their responses were the unempathetic chestnuts, “Well, they have to learn about the real world,” and “Well, I had to put up with it, why shouldn’t they?” The second is just kind of gross. The first reveals a number of misunderstandings around what “the real world” is like and how one might prepare for it. Most importantly, it contains the profoundly troubling idea that school, for our kids, is not “the real world.”

We compel attendance for more than a dozen years, and then we assert that it’s not real? That is some expert level, subtle, gaslight-y messaging going on. Let’s be clear: whatever else is going on, those years are the lives that kids are living. School is as real as it gets. And the kids are telling us what they think about that as plainly as they can.

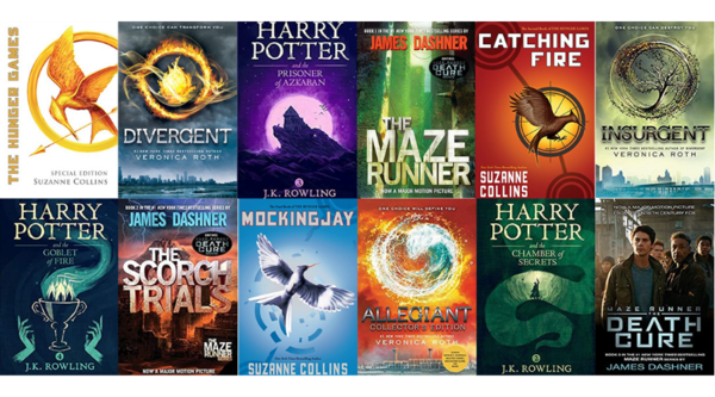

For example, did you notice, between 2010 and 2015, the remarkable wave of young adult novels in dystopian settings? Did you wonder what that was about? Art reveals the ethos, values, and beliefs of a culture, including youth culture at a given moment in time (e.g., School’s Out, Rebel Without a Cause, Huckleberry Finn, The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, et many cetera). The Dystopian Boom was not just some random trend in youth fiction reflecting their ideas about society at large. The reason these novels are loved by innumerable kids around the world is because they reflect the feelings and lives that kids are living right now. In school.1

Let’s see: Kids divided up by class, according to where their parents stood in the social and geographical order. Given arbitrary rules to operate by. Successes and failures accumulate over time and follow you to the end, determining outcomes. You win by doing better than other kids, and your merit is expressed exactly in terms of how you perform relative to other kids. Your goal is to earn a place in the world of the adults who set you on this path in the first place. So, which one is that? Hunger Games? Maze Runner? Harry Potter? Hard to tell. Is it the one where discipline is meted out by figures of positional authority? Are carceral methods used to control behavior? Is the space supervised by someone with a weapon? Do you have to ask permission to go to the bathroom?

There’s a reason why, when I have mentioned the duty to escape—the first duty of every prisoner is to escape— to a room of teachers they sort of gasp and start thinking of specific kids they’ve known.

In the work I’ve done over the past seven years, I’ve prioritized the importance of student engagement. I often (too often, maybe) point out that assessments don’t show us what kids know, they show us what kids are willing to show us that they know. It is always an option for a kid to opt out. I have more than once had kids say to me, “Look, Mr. Chapin, just give me the zero and stop talking to me!” In the economy of diminishment that some kids are forced to swim in, a “zero” is a small price to pay for a short time of peace.

So, yeah, it’s not as simple as “kids don’t like school,” but the complexity revealed by what kids are telling us about their lived experiences should not comfort us. In every one of these novels, there’s the “good adult” who does what they can to protect the kid from the system. We all see ourselves as that adult, and for some kids, we are that adult. But for many kids, we are the system, or tools of it. Maybe if we weren’t so devoted to the Project of School—for example, doing everything we can to recreate the coercive structures of school during a world-wide pandemic—and were more devoted to the Project of Learning, we could address this.