Our World Needs a New Taxonomy of Educational Imperatives

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

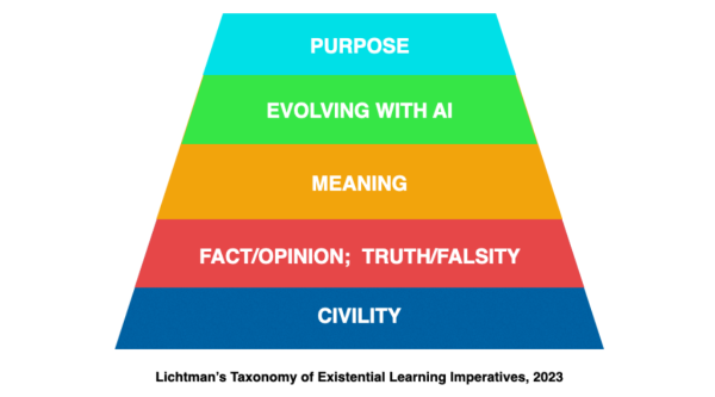

A new taxonomy of learning imperatives for K-12 education addresses existential challenges that are framing a future that has already begun, including rapid change, AI, and the breakdown of civil society.

A fundamental transformation in education, from teacher and subject-centered to student-centered “deeper” learning, has gained real traction in the last ten years. But the world demands that we frame an even higher-level paradigm designed to meet truly existential and rapidly evolving challenges of a world in 2020+ that did not exist just two decades ago.

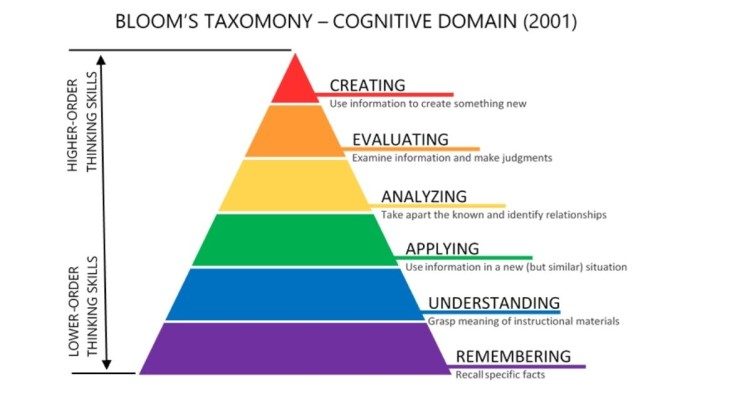

For much of the last century, most learning systems were forged within the pedagogical framework of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, first published in 1956.

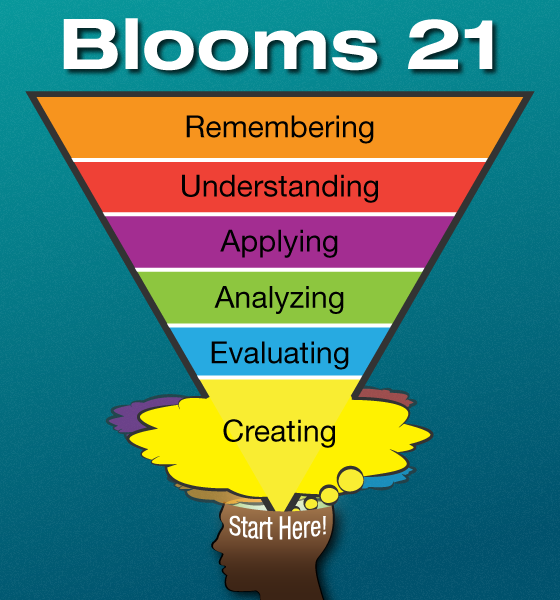

In the 2000’s, we realized what educational visionaries like John Dewey and Maria Montessori told us, and what so-called “progressive” schools have practiced, since the 1900’s: Bloom was wrong. The first articulation of “flipping” Bloom’s Taxonomy on its head that I encountered was by Shelley Wright in 2012.

We are re-finding that great learning comes through a pedagogy rooted in creating, experiencing, and engaging, not by having “learning” poured into students’ heads. We have a long way to go before we have rebuilt learning around “Inverted Bloom.” It requires major shifts in our thinking about the very structure of education. In fact, as I first wrote in 2015, it requires us to fundamentally change the school “operating system.” The good news is that many schools and educators have started that transformation. The bad news is that, in a world that is increasingly VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous), we already need to look past this transformation and craft an entirely new learning taxonomy that addresses a set of existential challenges that are framing a future that has already begun.

In 2021, I posited that the mission of education in a demonstrably VUCA world could be expressed in just two terms: meaning and purpose. I crafted a simple equation that balanced the needs and challenges of our rapidly changing world on one side with the meaning-plus-purpose mission of schools on the other. Since then, two events have caused me to iterate on that simple construct.

First, I have had the remarkable experience of traveling slowly around the country on my Wisdom Road project. I have driven 8,000 miles, interviewed many dozens of people, and I am only halfway done. I listen to an enormous diversity of people whose voices we almost never hear, learning what they think is most important about succeeding as a community, a society, and just as human beings who share both convergent and divergent values in this objectively VUCA world. They share many core values and a clear understanding of why our country has become increasingly divisive and angry, which has little to do with those shared values. Overwhelmingly, people tell me that we are in the process of losing our hold on foundational elements upon which our civil society rests.

Second, the first widely accessible AI tools have rapidly begun to fundamentally disrupt how we learn and how the world works with a speed and force that make earlier technologies pale in comparison. Just four months after launch, ChatGPT had 100 million users worldwide, the fastest adoption of technology in human history. It is already clear that AI will very quickly have an impact on the evolution of human learning, work, and interpersonal interactions that will be at least as disruptive as the agricultural, industrial, and information age revolutions. It is possible that AI will metaphorically compare, in terms of the depth and breadth of extinctions and openings of learning and job eco-niches, with the meteor that ended the reign of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

If we continue to design learning for the recent past, or even for today, we miss the big challenge targets that will determine success and failure in the future.

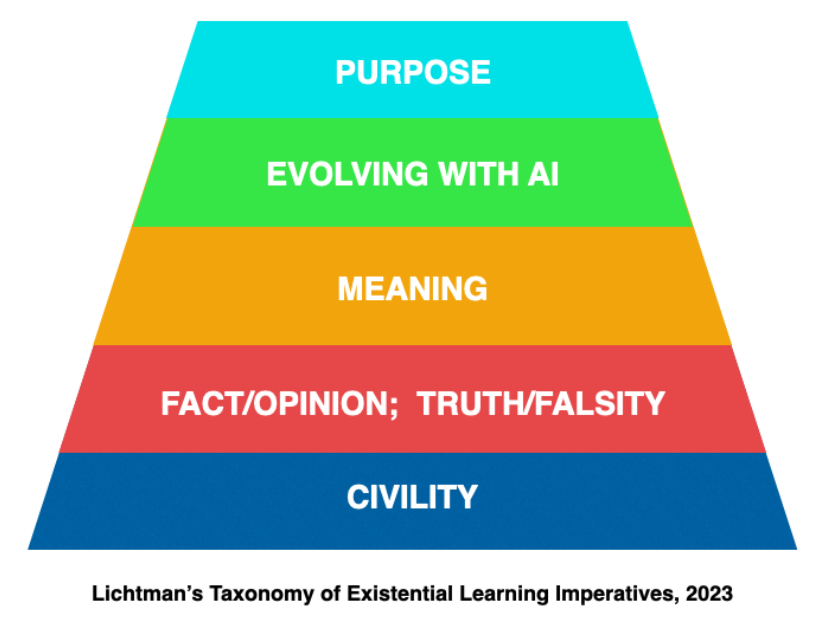

I believe there are five fundamental, and indeed existential, imperatives around which we must design education in and for the future. They occupy a mission level above pedagogy and other learning tactics; they are framing design elements of the new education operating system. And, they cannot be tackled in any random order; they need a hierarchy, a taxonomy. There is no guarantee that these five critical elements will be static over time. But if we continue to design learning for the recent past, or even for today, we miss the big challenge targets that will determine success and failure in the future.

These five imperatives are existential because if we don’t make significant progress in these areas, there is a high probability that education will fail in its primary role of preparing young people to engage in, and move forward with, the daunting trials we face as a civil society. Simply, what we need will not intersect with what the next generation is prepared to accomplish. I know that sounds overly dramatic. In this case, I don’t enjoy thinking that I am right, but I believe I am.

The Five Existential Imperatives of Learning

- Civility, particularly the ability and willingness to listen to “the other” and empathically engage in civil discourse, lies at the foundation of our democratic society. We are in the process of destroying this profound foundation through needless division, polarization, and the nurturing of fanaticism.

- Separating fact from opinion and truth from falsity. The rule of law and the basis of our civil structures require that we collectively hold certain things to be true, not subject to the selfish interests of those with the most power or the loudest voice. The culture wars have begun to seriously degrade fact, truth, and objectivity.

- Meaning, making sense of the world and how it got to where it is, requires that we learn and use knowledge that has been generated in the past in order to understand the context of today and prepare for the future. “Meaning” is the content and subject knowledge that has been the focus of education for millennia; we can’t toss it out.

- Finding our future human role in an AI-activated world. Even in its earliest iterations, AI exhibits skills and can already do jobs that have been the reserve of humans. It has been easy to say that AI will not be able to “create” like a human, but even that may be in doubt. We just don’t know yet.

- Purpose, as defined by Anthony Burrow at Cornell, is about “looking forward, aspiring to accomplish something that is ahead of you,” and it is defined by Heather Malin at Stanford as “motivated by a desire to be of consequence in the world.” Purpose has both a forward and outward orientation. In a world faced with social, environmental, and technology-induced challenges to our sustainability, helping young people discover their purpose as a function of these challenges surely must be at the top of our learning hierarchy.

Merely listing these principles is not enough. Like Bloom, they form a hierarchy not a buffet. One needs to merely ask the question: “For each, is there another that is a predicate? Must one or some come before others?” The answer is most certainly, “Yes.”

- Meaning, the understanding of knowledge that has been developed over human history, cannot be assumed valid without the ability to separate fact from opinion and objective truth from objective falsity. Since the rise of the internet these have become increasingly muddled, and in the age of AI the problem will be exponentially greater. Just when we thought the internet had brought access to the sum of human knowledge into our schools and homes, today’s political, economic, and cultural wars, not fact and truth, are driving what and how students learn.

- We cannot come to agreements around the roles, inputs, outputs, and impacts of fact/opinion and truth/falsity without the ability and willingness to engage civilly, as humans. We have to engage without predetermined battlefields sown with anger and rancor. We have to develop the skills and willingness to seek out, and listen to, people with different perspectives and world views, not the news, social, and political influencers that flood our lives, but the person in the next seat, community, state, or country. We have to connect with them human-to-human rather than as mere nodes across virtual networks.

- AI has already begun to reorder the roles of what we as humans can or should do/think/create. In order to thrive in this world, we must merge “meaning” (what we know from the past) with what makes us uniquely human, both as individuals and as a collective. And then we must evolve what we can do best in relation to the increasing power of AI.

- In order for each individual to find their purpose in the world, which should be an ultimate goal of all education, they must be able, willing, eager, driven, impassioned, and maybe even frightened into creating a personal path forward that has value and consequence, within the context of the existential challenges they and their fellow humans are facing. We can’t find our true purpose if we have not considered and struggled through the other building pieces of the hierarchy.

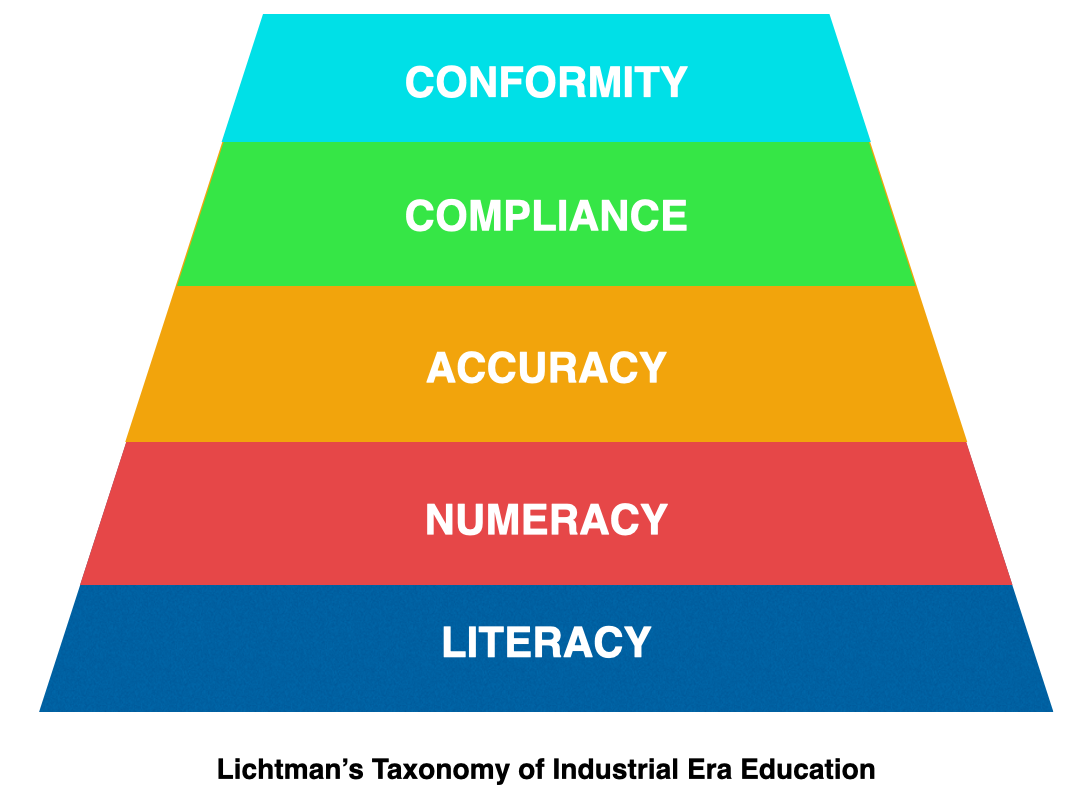

The last true revolution in education, the one designed to crank out literate cogs to fit into the industrial and colonial machines of the 19th century, was based on a taxonomy that ruled education for nearly 150 years. It determined that young people should become literate in order to fill the economic and political roles of the industrialized world. I don’t know if it was ever written down, but if it had been, the layers would be been something like this:

The designers of that age built a successful system of learning guided by these requirements. Now we have to do the same.

If my logic holds, then the Taxonomy of Learning Imperatives in 2023 is this:

Some schools are already wrestling with the elements of this taxonomy. Schools have focused on “meaning” as I have defined it here for the last 150 years. A few schools inextricably tie “what” students learn to not only media literacy skills (separating fact/opinion and truth/falsity) but also the skills of finding and listening to “the other” outside of their self-reinforcing bubbles. No school that I know of has articulated a clear understanding of how we will piece together the three lower levels of this taxonomy with AI capabilities and challenges that may ALWAYS outstrip our ability to predict their next evolution. Some schools state that their mission is to help students find their purpose in life, but do they have a framework for how that will happen? Are we hoping students find their purpose without going through the learning evolution or skills adoption that are required precedents for mapping a personal life trajectory?

This proposed taxonomy does NOT ask that we abandon or replace deeper learning pedagogies and human-centric skills development like collaboration, communication, critical thinking, creativity, and experiential and project-based learning. On the contrary, those are all tools that will, if deeply embedded in what takes place at school every day, help us work our way up through the challenges of this taxonomy.

This task is intimidating, to say the least. Educators are burdened with standards, over-testing, college entrance demands, pandemic recovery, teacher shortages, poor funding, politics, the culture wars, and more. Yet, I often recall the words of John Hunter, founder of The World Peace Game, a truly iconic teacher of the last half century. At one point he told his class of fourth graders, as they contemplated how to collaboratively solve the most complex challenge they had ever faced in school, “I don’t know how you will win this game, but I am completely confident you will do so.”

As I imagine the daunting challenges posed by this taxonomy, I wish I were as sanguine as John. My background is as a geologist, and the history of both humanity and the earth tells us that major disruptions often result in painful, even disastrous, short-term impacts. Evolution is a force of nature, with no guaranteed outcomes. Many have argued that the world is changing so rapidly that we are now beyond the point where we have the ability, either as individuals or organizations, to adapt to those changes in anything close to real time. But change is not going to slow down, and our need to evolve will not go away.

So, we either try or toss in the towel. This challenge of adopting a super-level taxonomy of learning imperatives is not one for just educators. It is a challenge for our society and likely our species to take on. I have no idea how, or if, we will succeed, but the urgency remains and will only grow stronger in the years to come.