Nurturing Identity and Belonging in a Challenging Time

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Educators at Barnstable Intermediate School design learning to promote student engagement, empowerment, and connections to each other and to the wider community.

In this time of stress and worry and uncertainty, it’s really important to do things that are authentic for the student. They can lose themselves and find meaning in the work they are doing. With all that’s going on, that is the only thing that is going to get a student to really engage and for real learning to happen.

—Alicia Roth, teacher of English as a Second Language, Barnstable Intermediate School

Nestled between Cape Cod Bay to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, Barnstable is the largest community on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in both population and land. Visitors to the area may not perceive its size, however, because Barnstable is made up of seven distinct villages, each with its own identity and character. Educators at Barnstable Intermediate School (BIS) strive to capture a similar small-town learning environment at their school. Although BIS serves nearly 800 students in sixth and seventh grades, the school encompasses smaller communities—called neighborhoods—as part of its work to reimagine student learning.

After first learning about NGLC’s MyWays Student Success Framework during a convening of Mass IDEAS grantees in February of 2019, BIS decided to dig further into how MyWays could be an important lever in redesigning their school. With funding, professional learning, and coaching support from Mass IDEAS, BIS is implementing a school-wide learning transformation that is aligned to MyWays’ whole-person definition of success.

Technology teacher Jenn Fredo recalls that the grant application process not only prompted them to transform the school model, but it also changed the way educators defined their roles and how they worked together. “What was so fortunate for us was having the chance to work as a team to rebuild the school. Whether or not we got the (Mass IDEAS implementation) grant, our conversations sparked collective energy around innovation.”

Mike Andrews, a sixth grade ELA teacher, explains the collaborative effort to broaden the school’s definition of success this way: “We as teachers are getting the opportunity to re-envision the entire curriculum through the whole-human framework of MyWays, and we took down the barriers imposed by curriculum maps. We wanted students to have authentic experiences, and we had the freedom to try to do that. I can create experiences that hold to the standards but look different.”

“Providing students opportunities to use their voice and have choice doesn’t mean we are diminishing rigor or losing sight of what has to be learned,” Mike argues, “but it’s also about finding what engages them. Especially this year, when the media is beating up on teachers (about learning loss), I want students to say, ‘I learned things, I tried things.’”

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I interviewed several BIS teachers about how the mindsets and practices that are emerging from their school transformation work have enabled them, in spite of the pandemic, to design learning that promotes student engagement, empowerment, and connections to each other and to the wider community. In particular, BIS educators shared stories from this past year about:

- Structures they use to create a “small school” experience

- An inclusive, real-world poetry project

- Musical composition as an expression of identity

- Projects that use food to celebrate cultures and serve the community

A Neighborly Approach to Learning

One of the five MyWays mindsets for transforming learning is “Invite the Community.” At BIS, this principle took the form of numerous town halls and community forums, where learners and adults shared their insights about the kind of school they wanted BIS to be. “We reached out, talked to them, did surveys, and looked at the data from outreach,” recalls Alicia. “What comment did we hear the most? People told us it was a big school.”

Mike adds, “Families feared their kids would get lost—that BIS felt like a two-year stopover. A place to go but not connect to as deeply.” Educators and school and district leaders responded to what they heard from the community and implemented the neighborhood concept in the fall of 2020.

As Mike explains, BIS pairs a sixth grade group with a seventh grade group to create neighborhood teams of learners and core subject educators. The four neighborhoods are named using the grade level and a compass direction, such as “6 South,” the name of Mike’s team. As in the practice of looping, learners in sixth grade will transition together to the next grade, maintaining the relationships they built with their peers and teachers from the previous year.

BIS educators report that they have had to delay some kinds of neighborhood bonding activities, like trips, originally planned for this year. Even amidst the challenges of the present moment, however, they are working together to create authentic and meaningful experiences to foster a sense of belonging and community.

Village Poetry Walk

Parents told us, “I want my kid to feel excited at school and feel safe to take a risk.” But students were so boxed in to the goal of “I want to get good grades,” and they did not even know why. They did not have the spark that little kids have. [Middle school] can be a surly age if kids don’t find a voice. We have to give them the opportunity to be their authentic selves and feel the authentic joy of learning.”

—Mike Andrews, sixth grade ELA teacher, South neighborhood

For years, Mike has started his ELA course with a unit on identity, culminating in a potluck dinner where learners could share their work with families. When the pandemic made it impossible to invite a large group into the school building, Mike, Jenn, Alicia, and special education teacher Caitlin Wojkowski teamed up to create “Where I’m From,” a community poetry walk project.

“What got kids excited in past years was gone,” he says. “If I had them just do a poem, it would be just another assignment. How could I get the students’ work out there, especially now, when the idea of community is more important than ever?” From a conversation with his class about the project, Mike recalls a “sincere and sweet” comment about showcasing on the grounds of local libraries. “That would be cool,” said one learner, “because older people love libraries, but they can’t go inside right now.”

In a partnership between BIS educators and the town’s director of arts and culture, the poetry assignment grew into an interdisciplinary learning experience and a community art walk project. In November 2020, the poems of 90 learners were displayed outside several village libraries throughout Barnstable. “It provided a way for families and the community to go on a socially distanced, in-town field trip and see the culture and identities of BIS learners,” Mike recalls.

The core of the project, he explains, is annotating and analyzing the poem “Where I’m From” by George Ella Lyon, which learners then used as a model to write their own poems. “We explored how you can look at a model but use your own voice,” he says. “I had some kids who wrote about being from hockey because ‘this is what matters to me.’ Another wrote three stanzas, one for each of his favorite local beaches.”

Teachers from other disciplines also shared their expertise with learners. For example, Jenn taught the young poets to use Adobe Spark and a QR code generator. These technology tools enabled learners to create and share artistic visualizations of their poems with anyone carrying a smartphone. “Kids were amazed,” says Jenn. “They said, ‘You mean anyone can pull this up on their phone?’ It was like a present for them.”

In addition to academic knowledge and skills, Mike and his colleagues designed the project to support development of MyWays competencies like positive mindsets around belonging, persistence, and believing that their work has value. “It was a lot of legwork,” Mike admits, “but how empowering to project yourself to an authentic audience? They were able to say ‘I am out there. I went to see my poem, and I saw other people looking at it, too.’”

Library visitors, like Mike and his daughter, read learners’ poems and used a QR code reader on their phones to access digital artwork, as well as a survey about the project. (Courtesy of Barnstable Intermediate School)

The poetry project was also intentionally inclusive of all 6th graders in the neighborhood, including beginner-level English Language Learners. Alicia describes how much her students, many of whom are native speakers of Portuguese, appreciated participating in the project. “When they were told they would write a poem in English, they were really excited, even though they thought it would be hard.” Alicia adapted the project by bringing in easier poems to serve as models. In the end, she says, “Students were proud of how they sounded in English and went with their families to see the poems.”

Learner-centered Music Projects

In collaboration with other BIS music teachers, choral director Mary Barth has embarked on an ambitious pandemic project: having learners update the school’s theme song. The goal is to support learners to write it, the chorus to sing it, the band and orchestra to play it, and finally to record it to share virtually this year and—as a communal expression of school identity—at in-person concerts in the future. According to Mary, the idea for such a monumental undertaking came up over the summer. She asked herself, “What’s something we can do right now that makes sense for the times we are in? What if we took this crazy situation and rewrote the school song?”

Mary notes that, “In a normal year, I might not have thought of veering away from my curriculum in this way.” At the same time, however, she is aware that her thinking about music education had begun to shift even before the pandemic. “The MyWays initiative has had a great impact. We’ve rethought the whole curriculum, especially in music. We follow the NAfME (National Association for Music Educators) standards, but I realize I can teach them any way I want.”

In Mary’s teaching practice, this mindset has resulted in new student-centered, project-based learning experiences. “I am taking maybe one key topic and turning it into a six-week project. I am conscious of what I am not doing, but I tell myself it’s OK because we are making real progress.” As for the school song project, Mary explains that her learners are working on music fundamentals and foundational elements like song structure, meter, and pitch. “I am amazed to see the growth. Kids are having fun, but they are also learning about what it means to be a songwriter.”

To connect learners with the real-world work of songwriting, Mary shows them interviews with professionals, like award-winning film score composer Danny Elfman, talking about how they write their songs. One pleasant surprise for Mary was discovering that nearly all of her students had already tried their hand at songwriting. “They brought in their journals. I had never seen this side of them, and there was a lot of talent.”

Working alongside Mary is Danielle Schroeter, a BIS music educator who teaches seventh grade and also directs the band. According to Danielle, having a school song is more than a traditional way to end concerts; it’s a way to create identity. To her, now is an ideal time to revisit the song and bring student voice into the process.

A commitment to learner voice is also central to Danielle’s approach to music education. For example, she is teaching a new music tech course this year as an alternative to a more traditional middle-school music appreciation class. “Sometimes seventh grade music is very passive. Kids are tentative about speaking up or picking up an unfamiliar instrument.”

To make learning more active, accessible, and engaging, even in a virtual setting, Danielle uses technology tools to support online musical collaboration, composition, and storytelling. For example, she explains, learners use Soundtrap to compose music together and tell stories using sound effects. They also learn first-hand about the work professionals do to create soundtracks and sound effects for films.

Right now, Danielle says, learners are celebrating the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth with a remix project, in which they are rewriting Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor. According to Danielle, they are listening to dozens of remixes and editing them in ways that “their personalities really come through. With the music tech approach, we can learn about Beethoven as we create a hip-hop mix.”

As evidence of learner engagement, Danielle refers to the data she receives from Soundtrap. “I don’t assign homework, but the software alerts me when learners save something they‘ve created. I see them working on the project in their free time and even over the holidays,” she observes. “I can also see other projects on their home screens. They are doing work and pursuing interests that are not even part of the assignment.”

Food for Comfort, Culture, and Service

You can tell that kids are excited. They want to know, “Can I make a second pie? Do you need more ingredients?” The tie to the community makes their faces light up.

—Caitlyn Sweeney, seventh grade ELA teacher, East neighborhood

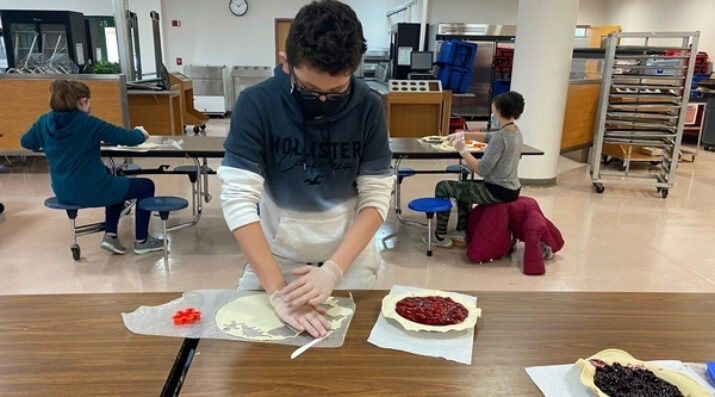

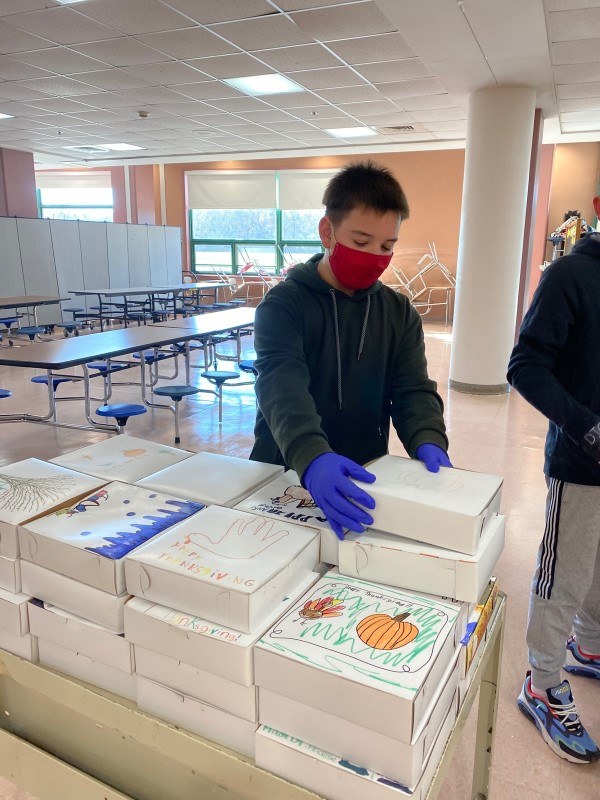

Although educators at BIS have embraced new definitions of success and are working to transform the learning experience for their students, some traditions live on and have become even more meaningful this year, in spite of the challenges posed by the pandemic. One of these is the traditional pie-making community service project. Caitlyn, a Barnstable alumna herself, remembers making pies when she was in seventh grade. “When those teachers retired, they asked me to carry it on. Even though this year it had to be six feet apart and spread out over two days (due to the hybrid schedule), the kids were very excited to give back to the community. It was a very positive experience.”

In keeping with a 28-year tradition, BIS learners made 91 Thanksgiving pies for the Salvation Army and Champ Homes transitional housing. (Courtesy of Barnstable Intermediate School)

The traditional pie project catalyzed a brand-new community enterprise for the East neighborhood this year as well, also centered on food. As technology teacher Jennifer Mullin observes, “It has been a challenge to have a neighborhood-wide activity to bring our students together. We wanted to make a connection between the two grade levels to start developing those relationships and establish a neighborhood identity. After the great success of the pie project, we decided, what better way than a collective cookbook?”

Caitlyn describes how learners are building the cookbook using Google slides. They are encouraged to share a recipe that relates to their family or culture and to include a photo and blurb about where it comes from. “Students are really excited about what others have shared and are eager to try them out. It’s been a great chance for learners to get to know each other and the teacher,” she says.

Jennifer adds, “I am loving the little blurbs students have put in about the roots of their recipe. If our COVID situation improves, it is our hope to have a neighborhood potluck where families will bring their recipe in for all to try. We have an extremely diverse neighborhood, and we are so excited to see the variety of foods included in our cookbook.”

Resources

- The student-facing write-up of the Where I’m From project describes the assignment and identifies the NGLC MyWays competencies and content standards the learning experience addresses.

- This digital brochure invites the community to participate in the Where I’m From poetry walks outside village libraries throughout Barnstable.

- In her project description for the Beethoven Remix Challenge, Danielle calls out the MyWays competencies and NAfME music standards her learners will work on as they create their unique Beethoven tributes.

- The “Design Learning” page of the MyWays website includes educator resources for whole-person learning, including a Real-World Learning Toolkit, exemplar projects, and learning design exercises.

Photo at top courtesy of Barnstable Intermediate School