Simplifying Competency Assessment: The One-Point Rubric

Topics

Educators are rethinking the purposes, forms, and nature of assessment. Beyond testing mastery of traditional content knowledge—an essential task, but not nearly sufficient—educators are designing assessment for learning as an integral part of the learning process.

Rubrics are challenging to develop and hard to use well. An alternative option to assess competencies can keep the best about rubrics while avoiding the pitfalls.

I have a confession to make. I kind of hate rubrics.

This is odd for a self-described progressive educator and co-founder at a competency-based school. But I have never been satisfied with how we designed or used rubrics, and while I have been fortunate enough to learn from colleagues at places like Two Rivers Learning Institute or Building 21 about what it takes to do it right, I am also keenly aware of the amount of effort, focus, and leadership capital that work requires, and I’m skeptical that we could marshall it given our other priorities. And yet without rubrics (and all of the work and learning that goes with them), how do schools like the Workshop School measure what we value? It’s not like there is a standardized test for Wayfinding, after all.

As friends and critics alike have reminded me over the years, schools like ours are often better at explaining what we’re not than what we are. (We’re not organized by subject! We don’t teach to the test!) Nothing has really changed my skepticism about the utility or value of standardized tests, but if we don’t center on tests then we damn sure better have other ways of showing people both inside and outside the school what our students are learning and how we know they’re learning it. Too often we (and many schools like us) fall short on that part of the work. As a result, we end up in defensive arguments about whether our learning models improve test scores. And while it turns out that in the aggregate the evidence on that front isn’t too bad, it’s a bit like weighing the efficacy of biking versus walking using step count when what you’re really interested in is travel time. It’s not enough to measure the wrong stuff well or to measure the right stuff badly–we have to measure the right stuff well.

The Benefits and the Pitfalls of Rubrics

To be slightly reductive, there are two basic approaches to developing rubrics. The first (and to be honest the one most aligned with best practice) is to have a single rubric for each competency (or set of competencies) that is used to assess all student work in that area. This roots the evaluation of student work squarely within a well-articulated competency framework that students see over and over. The theory here is that as they get these reps students will internalize both the competencies and performance criteria, ultimately reaching a point where they can self-assess and curate their own portfolios to show what they have learned and can do. The challenge with this approach is that the particulars of a given authentic assignment or performance can veer far away from the language of competencies and proficiency levels, leading to some pretty tortured interpretations of how an assignment demonstrates a given skill. (Or worse yet, narrowing what we ask students to do in order to conform to a rubric.)

For example, think of your favorite science, social studies, or problem-solving rubrics. Now imagine an assignment where you had to diagram and describe how a youth offender would be moved through the court system. You’re constructing a model for the process, but it’s not really about science or math, which is where most of your language around modeling lives. You’re researching a problem but the assignment you’re being given isn’t about the problem per se. You are learning social studies content but you’re not really getting intro sources, claims, or evidence. You could reasonably connect elements of any of these domains to the task at hand, but none are especially intuitive.

There is no definition of “not quite” or “way beyond” or anything else. The theory is to keep the focus tightly on the skills we’re after and be as transparent as possible about the work students need to do in order to demonstrate them.

The second approach is to customize rubrics to individual assignments. The benefit of this approach is that teachers can closely align assessment criteria with specific characteristics of an assignment, which makes it highly transparent to students. The drawbacks are that it’s a lot of work to create that many rubrics (which can also lead to quality control problems) and that students can have a clear idea of what good work looks like without necessarily understanding the skills it demonstrates.

And then there’s calibration: making sure that a rating of “4” or “Outstanding” or whatever it is in Classroom A is the same as in Classrooms B and C. Calibration can be amazing professional learning because it pushes staff to dive deep into assumptions about both the work and their students. It’s also super hard and incredibly time-consuming to get right. And far too often, even well-designed rubrics get cannibalized in practice, with lower levels on ratings scales becoming proxies for effort or attitude especially when translated into summative grades.

So to recap: I don’t like rubrics that are distant from the work, I don’t like rubrics that don’t tie to competencies, and I don’t like calibration. (I told you I kind of hate rubrics.)

For years I have been pondering what an alternative could look like, something that would keep what’s best about rubrics (connecting work to competencies, setting clear expectations, establishing a reference point for effective feedback) while avoiding the pitfalls. Which brings me to (drum roll please)… the one-point rubric.

Here I have to be honest: it’s not really a one-point rubric. Technically, it has three levels:

- Meets expectations

- Does not yet meet expectations

- Missing

It’s a one-point rubric in the sense that there is a single expectation that students are shooting for. There is no awesome-versus-crappy version of acceptable work. Students either meet the expectation or they do not. The key is in how those expectations are crafted, and this what splits the difference between the two approaches to rubric development described above.

Expectations: Where Artifacts Meet Learning Progressions

At the Workshop School, students spend about half their day doing interdisciplinary project work. Projects produce a variety of work, including demonstrations of process or habits, milestones, and final deliverables or performances. We assess these using a skills progression that is based on the NGLC MyWays Student Success Framework. The progressions outline what we expect students to be able to do at each grade level, culminating in graduates who are prepared to navigate the worlds of college, career, and community.

Defining expectations for an assignment or performance is a four-step process:

- Index the assignment to our skills framework. What specific skills is it intended to demonstrate?

- Determine performance criteria. Use the skills progression to define the level at which we expect a skill to be demonstrated given the student’s grade level.

- Define success. Given the focus and parameters of the assignment, what would student work need to look like in order to demonstrate the identified performance criteria?

- Refine and simplify. Explain in the fewest possible words and in the simplest possible terms what is expected for the assignment.

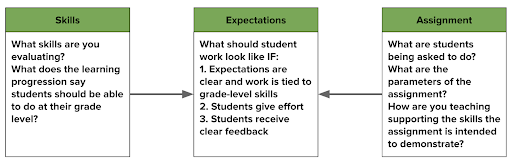

Taken together, the process looks something like this:

In this approach, expectations are the whole ball game. There is no definition of “not quite” or “way beyond” or anything else. The theory is to keep the focus tightly on the skills we’re after and be as transparent as possible about the work students need to do in order to demonstrate them.

From Expectations to Grades

In most high schools, there is some kind of crosswalk from rubric levels to a grading scale. We still live in a world of grades and GPA, and while it’s exciting to imagine alternatives, that world has most definitely not yet arrived. For conventional rubrics, the translation is fairly simple. The one-point rubric requires some rethinking. The solution we landed on at Workshop School works something like a Rotten Tomatoes score or a batting average: your grade is simply the percentage of work in your portfolio that meets expectations.

Here’s how that works in practice. When a teacher assesses a student’s work, they determine whether or not it meets the expectations defined for that specific assignment. If the answer is yes, the work is marked as meeting expectations and is added directly to the student’s portfolio. If the answer is no, the work is marked “does not yet meet expectations” and is returned to the student with clear, specific feedback about what they need to do in order to get their work over the bar. From that point, the student has seven days to revise and improve their work. At the end of that time period, the teacher re-assesses the work, changes the rating if necessary, and adds it to the portfolio either way. To stretch out our batting average analogy, work meeting expectations counts as a hit, while work that does not counts as an out.

The Payoff for Learning

The one-point rubric is a big shift for us. It requires everyone to think and work differently, especially students. It can feel like an all-or-nothing approach, especially if one superimposes a normal grading paradigm on it. (Internally, we had arguments about whether this was basically creating a system of As and Fs.) And coming out of a pandemic while still dealing with an explosion of community violence and trauma, it’s not like we don’t have other things to focus on. So why do it?

If we get it right, we pull off something that’s pretty rare in school innovation: nesting a totally alternate paradigm and approach within a conventional system without diluting it. We build a structure for aligning evidence (student work) with skills (via portfolios) in a way that is clear and transparent. We establish a set of practices whereby high-quality feedback is supported by systems and infrastructure. And we get students actively engaged in reflecting on what their work says about their skills, not just on how to earn an A.

Imagine a student graduating with hundreds of data points to show what they can do. Imagine being able to report learning outcomes without devolving into arguments about test scores. Imagine asking funders and district partners to hold us accountable on terms that align with our mission and model.

Will we realize that vision? I can’t say for sure, and I promise to share updates (good or bad!) in future posts. But what I do know for sure is that the effort is worth it.

All photos courtesy of the Workshop School.