Supporting Multilingual Learners in 2025 and Beyond: Finding the Balance between Rigor and Support

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

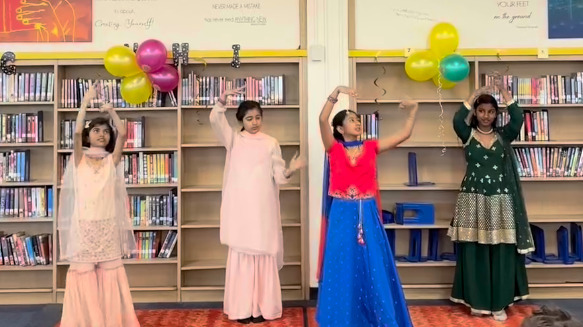

A rapidly changing student population has challenged educators in this middle school to collaborate to provide rigorous, meaningful next gen learning opportunities for all students, including multilingual learners.

The main entryway of Hackensack Middle School in New Jersey leads into an open hallway. On one side of the hallway is the dining hall, a newly-renovated facility equipped with six state-of-the art flat screen televisions. Blue and gold signs adorn the walls. As students enter, they are greeted with a big WELCOME TO THE HOME OF THE COMETS. And as they exit, they are reminded of the school values: PRIDE, PASSION, PURPOSE.

On the other side of the hallway is the gym, another newly-renovated space that serves nearly 1,400 students in grades 5-8 for their daily physical education classes and extracurricular activities. A blue and gold scoreboard reminds anyone who enters that they are entering, again, the home of the Comets.

But what is a Comet? Or more precisely, who is a Comet? Who gets to call Hackensack Middle School “home?”

An art installation in the middle of the hallway attempts to answer these questions. Silhouettes of hundreds of paper hands encircle a globe. Each hand is decorated with national flags. Some contain only one flag; the unmistakable patterns of the American flag, Mexican flag, and Ecuadorian flag stand out. Others tell a different story. On one, the green, black, and yellow of the Jamaican flag blends seamlessly into the red, blue, and white of the Dominican flag. On another, a Lebanese cedar tree and a Guatemalan quetzal paint a picture of a cross-continental, multi-hyphenated journey to Hackensack. A glance around the collage quickly becomes a game for students and teachers alike. Is that Ethiopia or Morocco? Turkey or Tunisia? Pakistan or Libya? Colombia or Venezuela? El Salvador or Honduras? Puerto Rico or the Philippines?

Credit: Dee Kalman and Amy Aguasvivas.

The demographics of the city of Hackensack have changed drastically in recent years, and this shift has had a sizable impact on schooling in the district. The Hispanic/Latino population in Hackensack has grown by nearly 40 percent in the last 20 years. In this same timeframe, the White population has decreased by more than 50 percent. More than half of all families in Hackensack now speak a language other than English at home. The South Asian and East Asian populations—primarily consisting of families from India and the Philippines—have increased the most rapidly, while migration from Colombia, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic has steadily increased since 2010. More than 17,000 Spanish speakers—nearly 40 percent of Hackensack’s population—call the city home.

At the school level, this demographic shift is even more pronounced. In the four years after the COVID-19 pandemic, the multilingual learner (ML) population more than doubled from just north of 10 percent of the student body population to 21 percent. During this same time, the percentage of students qualifying as “economically disadvantaged” has increased from 48 to 65 percent. And while it can be easy to get lost in statistics and figures, the reality is quite straightforward.

A rapidly changing student population has challenged educators in Hackensack to ideate, iterate, and collaborate around what it means to provide innovative, rigorous, meaningful “next gen” learning opportunities for all students, including our MLs, in Hackensack.

Credit: Dee Kalman and Amy Aguasvivas.

Multilingual Learners Are Not a Monolith

Any conversation around innovative student learning must begin with truly knowing students. In essence, who are we designing learning for?

This conversation takes on additional layers of importance for MLs, who are often labeled, stigmatized, and sequestered before they ever get an opportunity to demonstrate what they know and can do.

At Hackensack Middle School, this begins with a thorough intake and registration process. During this process, an administrative assistant gains information about a student’s educational history, native language literacy, attendance history, family dynamic, and living situation before officially enrolling them and building out their schedule. The purpose behind this is twofold.

First, the more information we can gain about the student, the better equipped we are to curate personalized learning opportunities that meet the student’s academic, linguistic, and social needs. And second, this information provides us with insight into any additional resources that a student or a family might require during their time at the middle school. Who, for example, might need access to a grief counselor? Housing and food resources? School-based mental health services? Technology support in school or at home?

This process ensures that before our MLs ever step foot in a Hackensack Middle School classroom, they are seen and valued for their lived experiences. But this only begins to scratch the surface of the “high rigor, high support” model toward which we strive, and we are constantly examining and reexamining the duality of this model to ensure that we meet the needs of all students at Hackensack Middle School.

Credit: Dee Kalman and Amy Aguasvivas

Part I: High Rigor Designed for Multilingual Learners

At Hackensack Middle School, our MLs arrive with different primary languages, different cultures, different prior schooling experiences, and varying degrees of resilience. Naturally, this is complex, but our educators choose to embrace this complexity and see it as a strength of our community.

To this end, we believe that high expectations and high support are not mutually exclusive. In fact, our entire instructional approach is designed around a “high rigor, high support” model. Classrooms are not quiet places where students continuously listen to a teacher lecture and passively receive information. Instead, classrooms, especially classrooms for MLs, are vibrant and filled with structured student conversations.

Teachers intentionally build scaffolds that are designed to ensure that students speak to one another, explore ideas, and, most importantly, build understanding collaboratively. As students engage with one another, teachers diligently monitor interactions. They are listening closely to their conversations, identifying where further support or challenge is needed, and adjusting instruction in real time. Participation is not peripheral to learning. It is the mechanism through which learning happens. Knowledge is co-created and reinforced through individual reflection and ultimately owned through repeated sharing and more participation. When this is done well, students are actively tailoring grade-level content to their needs and are fully invested in making learning their own.

In January, school and district leaders attended the Quality Teaching for English Learners (QTEL) Institute in Washington, D.C., a weeklong program centered on supporting educators who seek to enhance systems and practices around “deep, generative learning” for English Learners. Upon returning to Hackensack, our team immediately sought to implement their learning in the middle school.

During a recent classroom visit, we observed a lesson in Ms. A.’s room that exemplified what we mean by high rigor/high support for multilingual learners.

Students were engaged in a unit exploring migration and identity. That day’s lesson focused on personal narratives, using an excerpt from Enrique’s Journey, a nonfiction account of a teenager’s perilous travel from Honduras to the United States. The class was tasked with identifying central themes while exploring how personal experiences shape one’s sense of self.

To build prior knowledge before reading, students began with a think-pair-share activity in response to this reflective prompt:

“Describe a moment when you or someone you know had to make a difficult decision for the sake of family. What emotions were involved?”

Students wrote first; some in English, others in their home language or even with sketches or simple sentences. They then shared with a partner. Students were making deep connections to themes they would later analyze in the story.

What immediately stood out was the low-barrier entry of the opening question, which ensured all students could participate. The prompt required no prior knowledge, removing potential obstacles to engagement. These types of questions are essential for launching a lesson, they set the expectation that every student will contribute and reinforce the idea that participation is central to learning. Additionally, it’s hard to ignore the similarity to Building Thinking Classrooms (BTC), the math curriculum at HMS, which also begins with low-barrier entry activities as a warm-up. Subconsciously, students are being conditioned to believe that their backgrounds and divergent thinking are not only welcome but essential to the learning process.

The class then transitioned to a collaborative activity called Novel Ideas Only that was designed to elicit broad participation and encourage originality. Students were intentionally grouped into teams of four with mixed proficiency levels, so they could support one another with their varying degrees of language mastery.

Each student copied the prompt:

“Based on the title and our discussion, what big ideas or questions might this story explore?”

Each student contributed a unique idea or question to the group list, with the rule that no response could be repeated. Each member's idea or question was copied down by every member of the group, with the focus on “sharing the mic” and supporting one another with aspects of language like phrasing.

The key was not to race off answers. The goal, instead, was to support one another in ensuring that everyone's paper matched, emphasizing collaboration over individual achievement.

At the conclusion each team was required to share their Novel Ideas. The entire class listened for new ideas or questions to add to their already extensive list. Students also listened carefully for ideas or questions already mentioned, so they could cross them off their own lists.

What stood out was how the lesson smoothly transitioned from a low-barrier entry question to a more text-specific prompt focused on the title. This progression helped students make personal connections to the text while guiding them toward identifying key themes. Ms. A played a crucial role by actively monitoring student interactions to check for understanding and determine whether scaffolds needed to be adjusted. This was especially important in a middle school setting, where students can easily veer off track if not guided.

The observed lesson closely mirrors instructional practices used across disciplines at HMS. Lessons often begin with low-barrier entry points that allow all students to engage, then move into structured collaboration to increase access to the objective(s). Through peer discussion, students refine their thinking and synthesize ideas. Mastery isn’t measured solely by correctness, but by a student’s growing confidence in applying their learning and their increasing willingness to participate. The message is clear. Every student has something meaningful to contribute, and the act of sharing helps make learning visible and deepens understanding for the entire class.

Ms. A created and established a classroom culture where students enjoyed participating because they did not feel judged or criticized for mispronunciations or misspellings. After each group shared they were acknowledged with a “Thank you.” There was no feedback from Ms. A or peers; the goal was to amplify each student’s Novel Idea or question to help the class deepen their understanding of the central theme. Correct grammar and spelling were not the focus at this stage, addressing those later in the unit helps focus on the goal of identifying themes.

In that one lesson, we saw students practicing theme analysis, language development, collaborative skill building, and peer accountability all without sacrificing their voice or identity. They were not passive recipients of knowledge; they were actively building it together.

Ms. A. didn’t lower the bar. She raised the scaffolds.

Credit: Binghan Gu

Part II: High Support Designed for Multilingual Learners

Holding students accountable for rigorous, standards-aligned learning does not happen in a vacuum. At Hackensack Middle School, we have strived to create an ecosystem wherein educators work collaboratively to provide robust individualized supports and services for students. These tiered supports exist for all students, but they take on an additional level of urgency for our MLs, many of whom are reliant upon these supports to establish terra firma and begin their formal schooling experience in the United States.

These supports take on a variety of forms, but the common thread that binds them is access. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, students have access to adults in the building who speak their language and fully understand their culture. In main offices, counselor offices, social work suites, classrooms, and libraries, students are greeted by staff members from a variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Spanish-speaking counselors, administrators, and social workers collaborate with Arabic-speaking instructional coaches and Portuguese-speaking program directors. This linguistic and cultural diversity amongst faculty seeks to mirror the changing student demographics in Hackensack and ensures that all students have someone in the building who can relate to their experience.

Additionally, specific programming targeted to MLs aims to provide students, many of whom often exist on the periphery, with a sense of belonging. Bilingual classes have helped to establish a community for Spanish-speaking newcomer students who can access curricula in their native language while also receiving specific content-related English language support. Extracurricular clubs, mentorship groups, and summer learning activities targeted to MLs bring students who face similar challenges related to migration together.

And the larger Hackensack community has taken notice. This year, for example, the National Junior Honor Society includes recently-arrived newcomer MLs from Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic. These students were appointed to serve as translators during public-facing assemblies and were likewise chosen to serve as bilingual tour guides to support Spanish-speaking families during Orientation, Open House, Back to School Night, Parent-Teacher Conferences, and other community events. A student soloist from Ecuador sang beautifully (in Spanish and English!) during the Winter Choral Concert. A 5th grader from Mexico, dressed in a full unicorn onesie, was among the top female finishers in her first 5k trail run with the Hackensack Happy Feet Trail Running Club. The captain of the girls volleyball team spent her entire 8th grade year explaining “side-out scoring” to her Albanian-speaking family.

Put another way, our MLs are recognized and celebrated for their gifts, and the larger community sees and values their gifts—including their multilingualism and their culture—as assets that make Hackensack a stronger, more vibrant place to live.

This asset-based approach also serves a dual purpose in that it acts as an olive branch of sorts to Spanish-speaking families, many of whom have historically been disenfranchised from traditional public schools in the United States. Families see Spanish-speaking students and adults in leadership roles and in main offices and they feel welcomed. The simple act of translating family communication, for example, has increased family support significantly in recent years. And Spanish speaking nurses, social workers, counselors, and program coordinators enable our Spanish-speaking MLs and their families to take advantage of the myriad wraparound services available to Hackensack families.

Credit: Dee Kalman and Amy Aguasvivas.

Moving Forward

Rigor and support are not merely choices we make. They are ideals, a balance that we work hard to achieve every day. At Hackensack, we have learned that this balance comes from intentional design, from teamwork, and from seeing our multilingual learners as strengths to their classrooms and communities rather than problems in need of solutions.

Our advice to educators is simple: take the time to truly get to know your students, build meaningful relationships, create spaces where language connects rather than divides, and challenge all students while simultaneously supporting them.

So, who gets to call themselves a Comet?

If we have learned anything this year, it is that a Comet is a student who sees their identity reflected in the walls of their school and in the voices of those who teach them. A Comet is a learner who is challenged, supported, and celebrated. A Comet is someone who walks out of Hackensack Middle School with PRIDE in who they are, a PASSION for learning, and a clear PURPOSE shaped by their experiences. For our multilingual learners, this means more than just acquiring English; it means finding a home in Hackensack.

Learn More

Supporting Emergent Multilingual Learners with Next Gen Learning - Next gen learning is uniquely positioned to support emergent multilingual learners by integrating language and content in engaging, high-quality learning experiences.

Photo at top of multilingual learners at Hackensack Middle School. Credit: Dee Kalman and Amy Aguasvivas.

Note: This article was revised on 5/23/2025 with an updated description of the lesson in Ms. A.'s classroom and how the professional learning provided by the QTEL Institute influenced classroom practice and school-based professional learning.