Amplifying Student Voice in Self-Contained Classrooms

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

See, hear, and empower students in self-contained classrooms to lead through routines, curriculum, leadership roles, and cultural shifts.

We say we want every student’s voice heard. But what about students in self-contained classrooms—those in autism programs, life skills courses, or specialized support settings? They have a voice too. But it’s not always invited.

Sometimes, when someone finally does ask for their opinion, it’s not silence that follows—it’s a spark. Some students have been waiting for that moment. Others hesitate—not because they lack ideas, but because no one has ever shown them how to share them. They may need time, modeling, or someone who believes their voice matters. But the voice is there. And when it’s invited and nurtured, it grows.

This article explores what happens when we don’t just allow student voice in self-contained programs—but design for it. Through routines, curriculum, leadership roles, and cultural shifts, we can create classrooms where every student, regardless of support level, is seen, heard, and empowered to lead.

Created by Donna Phillips

Listening beyond Language

In many self-contained classrooms, students experience overlapping communication challenges: sensory regulation needs, expressive language barriers, processing delays, or behavior plans that emphasize compliance over connection. This can lead some people—especially those who haven’t taken the time to truly know these students—to assume they aren’t interested in leading, or worse, incapable of it.

But that belief erases potential.

Student voice doesn’t require perfect language. It requires intentional listening and inclusive structures.

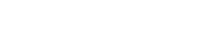

Last year, my co-teachers and I focused on helping students recognize and begin expressing their voice. Now, in Year 2, we’re building on that foundation—expanding their leadership, reflection, and self-advocacy. What began as guided participation has evolved into students contributing ideas, initiating routines, and showing up in ways that reflect their strengths.

Starting this fall, in my high school autism program, we’re introducing “Mic Check Monday,” where students will choose how to share what’s on their minds—using writing, art, visuals, or music. Some may pick a song that matches their mood. Others might write one sentence about their goals. One student consistently uses a color card to express his energy level. Every student participates, because every student has a way to speak.

We’re also planning to introduce short themed closings during the final 10 minutes of class—rotating topics like “Try It Tuesday,” “Wellness Wednesday,” or “Future Friday.” These reflective sessions will encourage students to share one takeaway, set a mini-goal, or spotlight a skill they used that day. It's a way to end on purpose—building voice through consistency, celebration, and self-awareness.

Created by Donna Phillips

Designing for Agency, Not Just Support

What if students in self-contained classrooms weren’t just supported but also invited to help shape the classroom itself?

We often build support systems for students—but imagine what could shift if we designed with them. Instead of only creating accommodations to help students access routines, what if we co-created those routines based on their feedback?

This year, we’ve begun reimagining what it could look like to co-design—not just accommodate. We’re starting to ask: how can students help shape our daily flow, identify supports that work for them, and suggest changes that reflect their learning preferences?

One student who struggles during group instruction, for instance, might help co-design a “replay station” where content can be reviewed at their own pace. It’s not just a behavior support—it’s ownership. It’s agency in action.

We’re not fully there yet. But this is the direction we’re reaching toward: a classroom shaped not only for students—but by them.

Curriculum Rewritten: When Voice Drives Content

We often talk about student choice within the curriculum—but how often do we build curriculum with our students in self-contained settings?

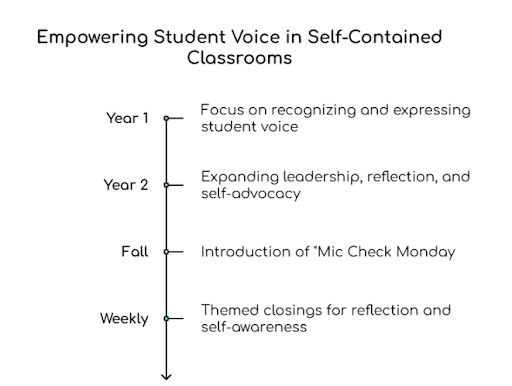

During a social studies unit focused on women’s history, I noticed a gap. When I asked students to name famous men, they could list many. But when I asked about famous women, responses were limited to Rosa Parks, the Statue of Liberty, "the lady who voted" (Susan B. Anthony), and Amelia Earhart. So, I introduced new figures to expand their perspectives.

We studied Junko Tabei, the first woman to summit Mount Everest, when students were exploring social-emotional learning (SEL) competencies like decision-making, stamina, courage, and teamwork. I tied Junko’s story to our own goal-setting work—how she pushed through challenges with grit and determination, just as we practice in class.

I also introduced Trudy Ederle, the first woman to swim across the English Channel. Students were fascinated, especially when they learned she had a disability. We did a mini film review afterward, but what stuck with them was her resilience. Her disability didn’t define her or hold her back—it became part of her strength. They really understood teamwork and not giving up and it gave them a better sense of pride that they could do things if they had a goal and set their mind to it.

We talked about how disability is not a disadvantage. It’s simply part of who someone is.

I build my curriculum to match standards, but I make sure it feels current, inclusive, and meaningful. These lessons weren’t just about the past—they helped students see themselves as part of the story. (Read more about this approach in my Edutopia article: History Lessons From Trailblazing Women)

Created by Donna Phillips

Leadership Roles within Reach

Student voice grows stronger when students are given real roles to lead.

In the coming fall, we’re planning to launch a “Kindness Crew”—students will nominate each other every other Monday for acts of kindness and deliver notes or stickers to other classrooms. It may seem simple, but it reshapes how students see themselves: as contributors, not just recipients of support. We’ll rotate roles each month, ensuring every student has a chance to lead. We'll also explore ways to partner with peer role models to extend collaboration.

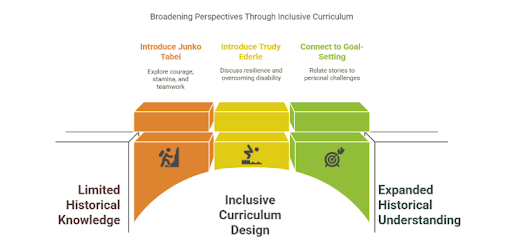

One student who is typically quiet may soon deliver a short message from his teacher to another self-contained classroom. Another student may have the opportunity to appear on the school announcements to promote the garden club or another school initiative. Some students have expressed an interest in pre-recording messages to share school tips—possibly connecting to the school news or newspaper occasionally.

Leadership doesn’t always look loud. But when we recognize it, it multiplies.

Behavior as a Form of Voice

When we interpret student behavior as communication rather than defiance, we unlock opportunities to co-create safer, more responsive environments.

Take one student—we’ll call him Jordan. He often bolted during overwhelming tasks. Rather than increasing consequences, we asked for his input. Using his words, he helped design a visual code system for needing a break: he could flash a green card, use a special word (“blueberry”), or head to one of our two “safe zones” without asking. Staff would signal back with a thumbs up.

This approach spread. Other students adopted the same signals, and it became a classroom norm. Self-regulation increased, stress behaviors decreased, and students started initiating coping strategies without prompting.

When we respect behavior as a form of voice, we build trust and dignity into our classrooms.

Created by Donna Phillips

Schoolwide Voice: From the Corner to the Center

Too often, students in self-contained programs are isolated from schoolwide initiatives. But their ideas belong in the larger ecosystem.

This fall, we’re hoping to pilot “Friday Features,” where our class will create short, pre-recorded video messages to share with the school: tips for staying calm during finals, favorite sensory-friendly music playlists, or simple jokes. We’d like to explore ways to occasionally tie this into the school news or newspaper.

The goal is to help students feel seen and amplify their voice through multiple formats.

Voice can be a bridge—not just to expression, but to belonging.

Created by Donna Phillips

Soft Skills, Real Stakes

Student voice is also career readiness.

When students learn to express preferences, give feedback, collaborate, or even respectfully disagree, they’re building the same soft skills future employers value.

We’ve tied voice-building to our social living, pre-vocational, and personal development classes, where students engage in peer interviews, classroom jobs, visual resumes, and presentation opportunities.

In From Service Cliff to Launch Pad, I explored how our transition-aged students need chances to practice real-world agency well before graduation. Voice isn’t separate from this—it is the foundation.

When a student tells us, “I don’t like that” or “I’d rather try this way,” they’re not being oppositional. They’re being prepared.

What Educators Can Do—Starting Now

If you want to bring more student voice into your self-contained classroom or program, here are five ways to start:

Use Expression Menus. Offer multiple ways for students to respond—speech, visuals, writing, music, movement, emoji-based check-ins, or audio recordings.

Co-Design Routines. Let students help set expectations, organize classroom layouts, or decide how transitions happen. Even choosing how to ask for help empowers them.

Elevate Small Roles. Create student jobs that reflect their strengths—greeter, tech helper, movement leader, visual schedule updater, kindness ambassador.

Turn Behavior into Strategy. Instead of focusing on “fixing” behaviors, ask what students are trying to tell you. Work with them to create calm-down plans, safe word systems, or signal cards.

Expand Voice Beyond the Room. Let students contribute to school newsletters, morning announcements, or campus projects. Advocate for their inclusion in planning committees or campus events.

The Real Shift: From Listening to Students to Listening with Them

Voice isn’t a one-time activity. It’s a culture shift. When we stop asking students to simply comply and start inviting them to shape the space, something changes. They see themselves not as part of a program—but as part of a community.

In How to Talk About Learning Differences With Your Students by Saini, I was cited as a source for inclusive classroom practice. That work began right here: listening to the students who are often not included in the narrative. Every insight in that piece came from my students first.

They’ve always had a voice. I just had to learn how to hear it.

Created by Donna Phillips

Final Thought

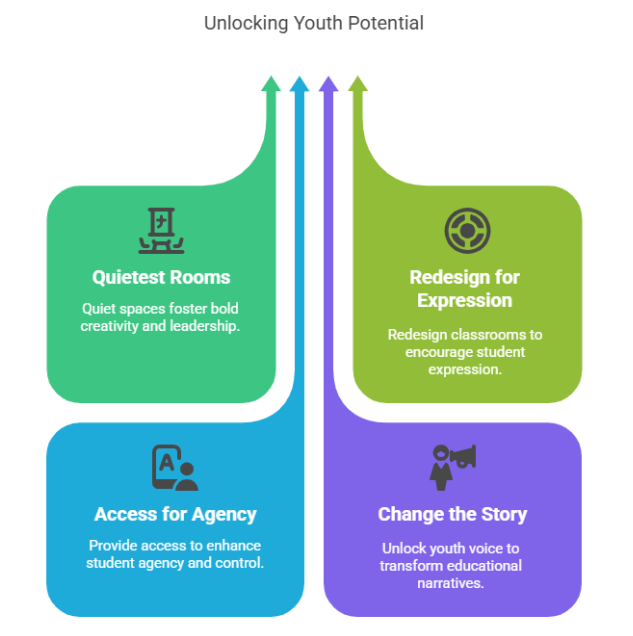

The quietest rooms can still be the boldest. In self-contained classrooms across the country, students are creating, leading, negotiating, and imagining—sometimes without saying a word.

It’s time we redesign not just for support, but for expression. Not just for access, but for agency.

Because when we unlock youth voice in every setting, we don’t just change a classroom—we change the story.

As Jennifer Gonzalez (2024) explains in her work on disability-sustaining pedagogy, this isn’t just about access—it’s about agency, interdependence, and pride in identity.

Photo at top by Lori Yerdon, CC BY 2.0.