The Problems Students, Families, Teachers, and Admins Hope We Solve Next Year

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Students, families, teachers, and school administrators view the challenges of the coming year differently—here's how to listen to their perspectives and build a way forward together.

Everyone is having a different pandemic. As you plan for next year, do you truly understand all of the different pandemics that people in your school community have experienced?

For some young people, the pandemic has been a crushing experience marked by the collapse of social connections, anxiety from economic recession, mourning of lost loved ones, and remote learning efforts that fail to engage students meaningfully. For another, likely smaller, group, the pandemic has been a liberation, where students have discovered that they like online learning, self-directed inquiry, greater autonomy, and the comforts of home. For some students, particularly in rural parts of the United States, young people put on masks (or didn’t) and experienced a relatively normal year of school.

Just as there are different perceptions among students, there are also great differences between stakeholder groups. Students, parents and caregivers, teachers, and school leaders have all traveled different paths through the last 15 months. The gaps between the perspectives of national policymakers and those who spend every day in schools are particularly stark. National commentators have largely settled on a narrative of “learning loss” to frame, explain, and move forward from this year. In this narrative, students failed to make typical progress on their coverage and understanding of standards-aligned curricula, so the primary task of schools is to remediate this content coverage through extended school time, summer school, and tutoring. For many of the students and teachers that my colleagues and I have interviewed, this narrative is almost unrecognizable. Teachers and students have gone to heroic efforts to continue learning, and standards-aligned content learning and retention is always quite variable from year to year. The distinctive losses from this year that they see don’t relate to standards-aligned content but to the losses of friends and family members who have died and the social bonds that have eroded during lockdowns and social distancing. Education policymakers and those who work in schools are definitely experiencing different pandemics.

Ask Your School Stakeholders for Their Perspectives

Efforts to envision how schools will open next year need to start from reflections about how differently people view the present and imagine the future. To help folks begin to see these different pandemics and to incorporate these different experiences in their planning, my colleague Jal Mehta of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and I conducted a series of design charrettes that included students, teachers, family members, and school leaders from schools and communities across the nation. One of the exercises in these meetings was reflecting on how different groups define the problems to solve next year. We ran the exercise as follows:

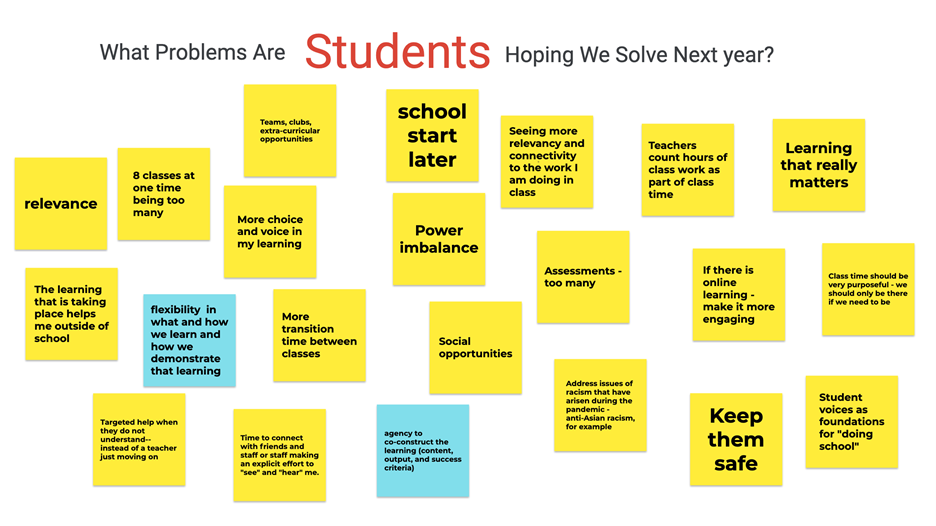

Use a collaborative online notetaking space (Google Jamboard, Miro, etc.), and create four slides [Template Here]. For the first slide, ask participants to reflect on the question, “What problems are *students* hoping we solve next year?” Then on the three subsequent slides, ask participants to reflect on, “What problems are [teachers | families | administrators] hoping we solve next year?”

We’ve conducted these exercises in multi-stakeholder groups, and we’ve encouraged participants to start on the notepad that most represents their perspective (as a student, or as a teacher, and so forth). Then we ask them to add additional notes on other pages based on how they perceive other stakeholders as framing the problem. So a student might start on the students notepad, leave a few ideas, and then move on to the families and teachers pages and imagine how their parents and classroom teachers would answer these questions. After about 15 minutes of posting notes, we ask everyone to read all four slides and look for common themes within pages, differences across perspectives, and notes that seem to stand out for offering unique, interesting perspectives.

Build the School Year that Your Stakeholders Need

In all of our meetings, we’ve observed that each stakeholder group views the challenges of the coming year differently—to varying degrees they all have different problems to solve. Everyone is having a different pandemic.

From student perspectives, we read over and over about how their social lives have wilted this year, and how eager they are to have time to connect with friends and reengage in sports and extracurricular activities. They are hoping that some of the autonomy and flexibility that they experienced this year—more flexible time for self-directed work, more freedom to eat and stretch, later start times—can persist in some form as school buildings continue to reopen. Families and teachers are eager to continue to strengthen home-school connections that have been deepened this year. Teachers are completely exhausted, and while they hope to carry forward useful innovations from this year, they are also anxious about resting up enough to be healthy and sane next year. In looking at the administrators’ slide, we have been struck by how many entries are framed as questions: how to reengage learners, how to reenergize staff, how to strategically use budget windfalls from stimulus, how to carry forward the best of what was accomplished in this past year.

As you host planning conversations for next year in your community, these kinds of perspective-taking exercises can help people recognize how differently folks in a single community can understand the problems we face and the pathway forward. Everyone is having a different pandemic, but the response to the next phase of the pandemic can be one we build together.

Photo at top courtesy of MIT Teaching Systems Lab.