Three Ways Franklin Is Doing High School Differently

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Franklin High School is moving “from Portrait to Practice” and doing high school differently with three systems-level changes.

It feels dangerous to talk about a system change that is not yet part of the culture of a community. Will sharing too early make us look like failures if things don’t work out? Is it too early to share because we don't have years of data that show results? What if implementation has not been pretty? What if not every community member is bought in?

Or should we share, because the actual commitment to try something new, even with the risk of failure, is inspiration for someone else to try something new? Afterall, if no one goes first, then no one goes.

Just about twenty years ago, Franklin High School in New Hampshire did go first and I wish they had documented their journey then. As one of the first schools to pilot Competency Based Assessment not only in the state but also in the country, they were attempting to do high school differently. I was just starting my teaching career and it was inspiring to be part of a good shift in education.

Unfortunately, New Hampshire’s progressive policy did not yield a huge shift in high school design because, like many education policies in New Hampshire, it was the worst kind of mandate, an unfunded one. Despite taking a first step toward a new approach to teaching and learning, the lack of funding and all the privileges that come with it meant that Franklin has too often taken one step forward and three steps back.

I want to note here that money can’t just buy systemic change. I have this conversation often when talking about school funding, especially in New Hampshire. For us to truly improve the student experience, we can’t just give more money to schools and poof things will be perfect. Lasting change requires mindset shifts, a commitment to trial and error, and of course time to learn new skills and knowledge.

This boost of support has really helped Franklin over the last three years make little changes that in 2023-2024 became significant change, even if they’re still working out the kinks.

In 2019, Franklin received a grant to create a Portrait of a Graduate from Barr Foundation, which has invested millions to help New England schools in “Doing High School Differently.” This boost of support both financially and through resources and community has really helped Franklin over the last three years make little changes that in 2023-2024 became significant change, even if they’re still working out the kinks.

Here are three ways Franklin is doing high school differently:

#1. Defining a Credit by Evidence

When New Hampshire minimum standards were updated to move schools from defining a credit based on seat time to defining credits based on competency, the structures in schools did not change that much.

Very few schools actually addressed the question of evidence, and specifically how much evidence and what kind of evidence did a student need to produce in order to demonstrate the skills necessary to earn a credit? For the purpose of equity and high standards, sufficiency really should be defined.

It’s important to note that determining sufficiency is not an exact science. I often use phlebotomy as an example when discussing sufficiency because the diversity of human bodies is just as diverse as the learners in our schools. How many times does a phlebotomy student need to demonstrate that they can draw blood and under how many different circumstances before they get certified? How many dehydrated patients? How many underweight patients? How many children? How many pregnant women? How many people with weak veins? How many people with severe anxiety? There’s not one perfect exact answer; it’s a guideline.

Similarly, how can we know a student is a good collaborator, or good enough to earn a credit where collaboration is a competency? How much evidence do we need? When is it produced? Under what circumstances?

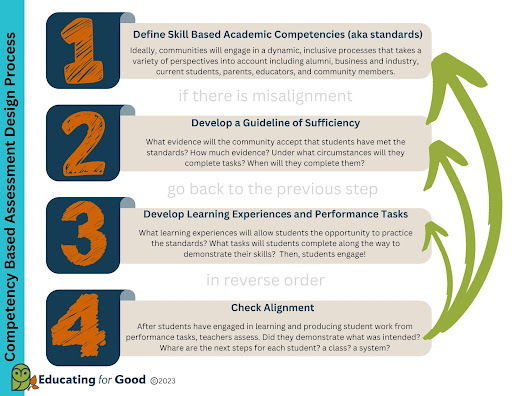

Competency-Based Assessment Design Process. Credit: Educating for Good

Without sufficiency defined, a competency-based system is not much different than when teachers add or take away assignments based on the time. We got through that unit early, let's add another test whose score will contribute to the overall average. Or, probably more frequently, we didn't get through the curriculum so we just won't do those last two units, making the earlier scores "count" more than originally anticipated.

So, as part of Franklin’s journey, once the Portrait of a Franklin Graduate and corresponding competencies were defined, the next decision was about evidence, what kind, and how much. The answer for Franklin right now is Signature Tasks.

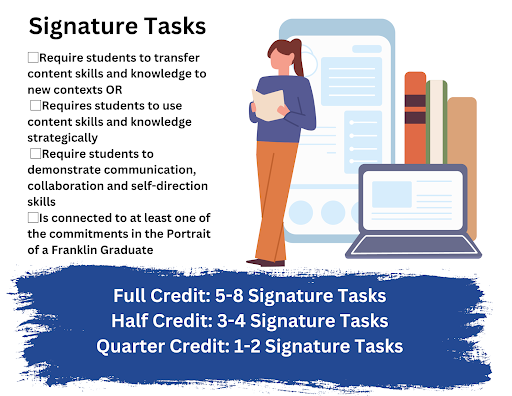

Signature Tasks. Credit: Franklin Schools SAU #18

As part of the district’s plan to bring its “Portrait into Practice,” students at Franklin are completing five to eight Signature Tasks for each credit they earn. Half credit classes require between three and four tasks. This doesn’t mean that only Signature Task evidence is used in a teacher's overall assessment of a student's skills. It does mean however that all students are held to basic evidence expectations when they earn a credit.

As a next step for Franklin, teachers will refine their Signature Tasks to ensure they are quality and aligned with the school’s instructional vision. And they’ll revisit the Guideline of Sufficiency, because maybe 5-8 is too much or not enough. They won’t know, however, until they test it out.

#2. Using the Community as the Campus

One of the most important things we learned about the Franklin community when we canvassed for the initial portrait is that Franklin is rich in human capital. Many community members and businesses are ready and willing to share their knowledge, their spaces, and their skills with Franklin students. And although there have been some bright spots over the years, learning in and with community is not yet part of the rhythm of Franklin’s system.

One of the great things about being in a cohort with other schools and districts undergoing similar change is the constant flow of ideas. Somewhere along the way, the Franklin team heard Margarita Muñiz Academy, another Barr grantee, use the language “City as Campus” to describe their vision for learning. That resonated deeply with the Franklin team as this idea, learning in the community, is part of their instructional vision.

Franklin students Julia, Oliver, and Patrick at MassMOCA, learning with other Barr grantees in the Berkshire County, Massachusetts. Two or three times a year, the Franklin team connects with other schools that are also rethinking the high school experience. Credit: Carisa Corrow

And, the team recognized that Franklin is not Boston and they would need the wider New Hampshire community to help serve as an expanded campus. Additionally, Franklin’s vision includes bringing more guest speakers and guest facilitators to the school. More and more, Franklin is using the Community as the Campus. It is not unusual to see multiple small groups of students passing each other on their way to different learning excursions during the school day.

One of the biggest feats so far this year, was to send all the students on a learning excursion with their We CONNECT Crews. On a Wednesday, in the middle or October, the school halls were quiet from 9-1 as all students and staff were off learning with facilitators from Kimball Jenkins Art School, touring the Merrimack river with guides from Outdoor New England, exploring Squam Lakes Science Center, and discovering how to work collaboratively to solve an escape room and corn maze.

Students from Franklin High School’s Commmunity Exploration course watch Louise Nylander, owner of Downtown Crepes in Franklin, New Hampshire, make a traditional crepe. Credit: Carisa Corrow

For so long we’ve been conditioned to accept that formal learning has to take place in a school, in a classroom with four walls, and with desks in some standard formation. A simple change in perception, to expand the definition of campus, is making foundational changes for future learning experiences for Franklin students.

#3. Scheduling a Little Differently

Of course the shift in where learning happens would not be possible if the team didn’t consider when learning happens. Franklin leadership recognized that the schedule, as it was and had been, was not conducive to this vision. In the spring of 2023, with design specifications from the superintendent, a team of 12 including teachers, student support personnel, an administrator, and students took on the task of creating a new schedule.

There are two types of days at Franklin. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays are four ninety minute blocks. Tuesdays and Thursdays are reserved for Project Blocks that are two hours each. This is a stationary schedule, so if there’s no school on a Tuesday, that day just does not happen.

Credit: Franklin Schools SAU #18

After nearly nine weeks, it’s certainly not working perfectly, yet it has opened up some opportunities that students would not have otherwise been able to take advantage of. The planetarium is only 25 minutes away, so classes can get there, take in an hour of learning, and then get back to school before the project block is over. Similarly, the community can literally be the campus, as walking field trips are now the norm.

A schedule shift has also been helpful as Franklin, like most schools, is grappling with the teacher shortage. More than ever students are dual enrolled in the Community College System of New Hampshire fulfilling science and math high school requirements and earning college credit. College faculty are also at Franklin High School twice a week offering classes, which eliminates transportation barriers.

After the first nine weeks of Project Blocks, evidence of student work through final projects and presentations are emerging. The Youth and Government final project was an evening mock city council meeting in partnership with city council, school board, and city department heads. Attendance, especially for an evening Signature Task, was stellar. In the Puppetry project students performed their puppet show at the elementary school, ensuring each group of students got a high quality theatrical experience. And the students completing the 15 Minutes in Space project are well on their way to creating a model of the space capsule that New Hampshire native Alan Shepard sat in during NASA's first flight to space.

A commitment to ensuring student involvement in helping to address these and other issues is another way Franklin is changing.

Other changes are taking shape as well, including a new maker space and media lab as resources for student projects, relocating administrator offices for more visibility, and Instructional Rounds with teachers and students. Franklin is also beginning to implement Antioch's Critical Skills framework to support rigorous, relevant, and engaging learning experiences in all classes.

Of course, there are bumps in the road. Franklin faces the same challenges as other schools including cell phones, vaping, and the lingering effects of the pandemic. A commitment to ensuring student involvement in helping to address these and other issues is another way Franklin is changing.

The ultimate goal at Franklin is to have a high quality student centered learning environment where students leave fully committed to their own learning, their community, and their wellness as well as demonstrating commitments to responsibility, resourcefulness, and humanity. In order to create this environment, structural shifts had to happen.

Though they aren't where they hope to be yet, they are definitely “doing high school differently.”