VIDA for Life: A Q&A with Vista Innovation & Design Academy

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

One California middle school went from near state takeover to a vibrant learning community of innovation and creativity, transforming itself with the staff and students who were already there. This is its story of transformation, as told by the school’s principal.

Schools can either disrupt or perpetuate the status quo. Your birth certificate is not the story of your life.

When Vista Unified School District (VUSD) embarked on its journey to transform learning, Washington Middle School took a place at the forefront of our districtwide change effort. In 2013, as a result of consistently low performance on achievement tests, the school, which primarily served Latinx students from low-income households, was poised for state takeover under the provisions of No Child Left Behind.

“Washington Middle” as such did cease to exist, but it was not taken over. Instead, it transformed itself, for and with the staff and students who were already there, district leaders like then-superintendent Devin Vodicka, innovators from the Stanford d.school, and a new principal (co-author Eric). Together, the team recognized that the "why” for the school’s failure was a lack of engagement; the predominant population—LatinX youth below the poverty line—did not see themselves in the school and what was done to them at school.. So, the Washington Middle School community reimagined and redesigned virtually every aspect of the program in order to engage learners with empathy, creativity, and a culture of innovation.

In August 2014, Washington Middle School became VIDA, a magnet middle school serving learners in grades six through eight in our district. The name is both an acronym for Vista Innovation & Design Academy and the Spanish word vida, which means life. In this way, the name reflects the school’s focus on developing the whole person and preparing students for success in their “vida after VIDA.”

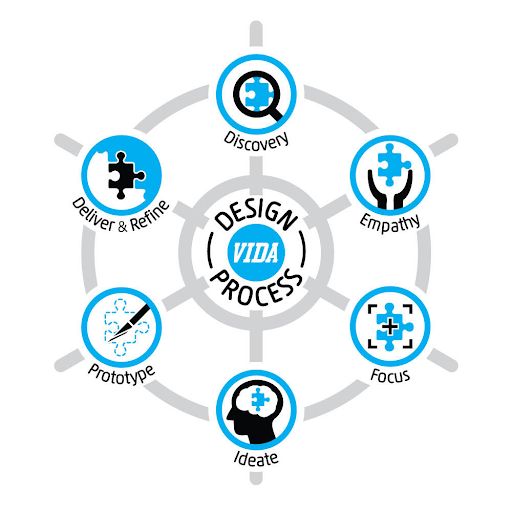

Today, VIDA provides learners with a community-defined and culturally responsive approach to teaching and learning based on design thinking.

In Q&A style, where Nicole asks the questions and Eric responds, we tell the story of VIDA’s transformation and how the school fosters innovation and creativity among learners and adults alike.

What was your ‘why’ for leaving your position as assistant principal at Vista High School to take on the challenge of transforming Washington Middle?

At Vista High, I spent a lot of time in way too many conversations with moms, typically through a translator, about difficult things their kids were going through: rehab, pregnant, leaving for a continuation school, fights, drugs, any number of negative issues an assistant principal at a centrally located, large high school would deal with. And so, probably a year in, or year two, the translator and I looked at each other after a meeting and started having this discussion around, “I wonder if there’s any commonality about when these parents feel like they lost their kids.” And moms typically were able to recount that back to middle school and specifically about seventh grade when they thought about it. And so my thoughts came around to, “Why am I sitting at high school, when it sounds like middle school is when we are losing so many kids?”

My dissertation was on high-achieving Latinx youth, so Washington spoke to my heart. It really spoke to what I wanted to be and where I wanted to be. And I knew that the superintendent at the time, Devin Vodicka, was working toward trying to re-imagine the school in some way.

VIDA uses the design thinking process to nourish creative thinking skills that will empower students to apply what they learn and create non-traditional solutions to yesterday’s, today’s, and tomorrow’s problems.

How did the transformation from Washington to Vista Innovation & Design Academy unfold?

Devin Vodicka had already done the work of explaining to the teachers that something was going to have to change. They didn’t know what it was, only that the new principal was going to work with them on figuring it out. At the time, Jo Boaler, the mathematics education professor at Stanford University, was doing a lot of growth mindset work with our Director of Math at the district. Jo had a very close relationship with four teachers at Washington Middle School and knew that these teachers were willing to try anything.

When the math teachers explained to Jo what we were trying to do, she said, “You guys should look up something called the d.school at Stanford University. They have a really unique problem-solving process built around creativity and empathy. And I think it’d be a perfect process for you to use.” So this was nine years ago, before “design thinking” was a buzz word and all popular. I had just come on, but we checked it out. We liked it. So we used the design thinking change process to help reimagine the school.

The transformation was with the same teachers, in the same building, with the same kids matriculating through.

We had to start with things we needed: a vision, a mission, and values. We had 98 percent faculty attendance to those types of after school sessions, voting for those things, and feedback sessions. Our leadership team was called the Magnet Steering Committee. There were seven teachers on the committee, and they were voted on by their peers through a vote held by the site union rep. Student engagement had to be our first priority, and the key was empathy—walking in the shoes of others. We talked to students, to alumni, parents, teachers, and even to the owner of the 7-Eleven on the corner.

We were impressed by the impossible amount of creativity and energy that the design thinking process brought out in our team. I was impressed by the camaraderie and culture. And so, we decided to turn design thinking into pedagogy. VIDA was going to focus on the arts, STEM, humanities, and wellness. And a culture of innovation. We share a fundamental belief that the mind can be trained to be more creative—where creativity and skills come together is innovation.

That founding team of seven prepared slide decks and presentations for what design thinking in the content areas would look like—in humanities, STEM, and electives. All of the middle schools in our district have one hour every Monday of teacher collaboration time. They would do presentations during that time. They would talk about what it would look like. And those were the touchpoints for a lot of the faculty.

So teachers had a year of planning, so to speak. By planning, I mean that after working at a really tough school all day long, they would then at night go try and figure it out and have late meetings and plan. One of the reasons why we get a lot of attention is we’re not a brand new shiny building that started from scratch. We’re not a charter that just kind of pops up and works its own rules. We’re a district school with a union, where the transformation was with the same teachers in the same building with the same kids matriculating through.

After the last day of Washington Middle School ever, the next day we started a three-day training for project-based learning (PBL), which provided a curricular structure for design thinking, which could have been very nebulous otherwise. We spent a lot of time those first three years doing training and looking at different ways of implementing design thinking. We gave teachers latitude and talked about how you could integrate mindsets and dispositions of true brainstorming and gathering empathy, the right way to interview and do observations. You could do character analysis in English language arts and get really deep by talking about empathy and observation and making inferences. Maybe in science, prototyping was really easy for you. Well, there’s methodology around that. So teach the methodology that we’re talking about.

And then we have 6 Minimum Days a year by the district calendar. Kids get out after 3 hours of class. We don’t “do school” per se on those days. We have design challenges, on-the-job training for teachers to actually go through the whole process of design thinking and to ensure that students are getting the opportunity to put all the design thinking pieces together into actual design challenges. And now we’re nine years in. Teachers are doing design challenges all over the place and in all sorts of content areas.

Listen to the Podcast

Hear Eric and teacher David Ruiz talk about VIDA’s block schedule and opportunities for all learners to access electives in this five-minute podcast.

How does VIDA support student engagement and relevance?

When I got here, only 18 percent of students had electives. It was really “popular” in California’s public schools, under NCLB, at that time to have kids doing interventions upon interventions upon interventions. Washington Middle School had actually reduced the number of minutes in each period and included an additional ninth period in the day for all students so that more interventions could be available. And one of the things that data told us was that there was an inverse relationship between the increase in academic interventions that were being forced upon kids and actual academic achievement. So interventions were going up, yet achievement was going down, and all the while discipline was going up. It was all out of whack and made no sense. Essentially, when you talk about the “school-to-jail pipeline,” we were a construction project for that, and it’s not lost on me that the school is located one mile down the street from the jail and courthouse for the northern portion of the county.

We decided that engagement was going to become our first intervention. That’s what we were going to do. That’s the hill we were going to die on. VIDA was either going to succeed or fail based on the idea of student engagement. We planned to build that naturally through PBL, design thinking, personalized learning, and student choice; so that students would enjoy themselves more and would have more access points to see relevance between what they’re doing in school and their lives.

With this very crystallized, laser focus on engagement, we wanted to make sure every single kid, regardless of IEP status, regardless of language level or anything else, had a great opportunity and a reason to come to school every single day.

And since we were looking at doing something different, we decided that we would operate differently. We decided we needed a new bell schedule. We got rid of double dosing English, we got rid of double dosing math. We went back to an eight period day just like the other schools, but we went to a block schedule. So we had more time to go more deeply. We believe that technical changes like bell schedules or furniture, room setups, technology, and other things should only happen in response to the pedagogy being done. But in my experiences with schools across America, it happens in reverse.

Students who have an IEP (Individualized Education Plan), they’re often required to have a study skills class or some sort of support, or if a student is in English language development, it’s required that they have an English language development class. And you can’t take away PE (physical education) because that’s required. So kids lose electives, right? That’s what happens to kids with disabilities, ELD kids, the most vulnerable. Automatically, the first thing they lose is one of the major reasons kids look forward to coming to school.

Here’s what we did. With this very crystallized, laser focus on engagement, we wanted to make sure every single kid, regardless of IEP status, regardless of language level or anything else, had a great opportunity and a reason to come to school every single day. And so we created a special 50-minute class, and we attached that to their 40-minute lunch to fill a 90-minute block of space every single day. Those classes—RC (remote control) race car class, flight and rocketry, or other things—well, those classes are tied to the student lunch and you can’t take them out of it because then they would lose their lunch period.

And teachers must also be engaged. They must be excited. They must have the opportunity to do something that they’ve always wanted to do with kids that they’ve not been allowed to do. With that mantra, we’ve had teachers invent these really fun classes. And so by tending to the souls of the adults, we serve the needs and the interests of the students.

That [first] year we saw a 92 percent reduction in suspensions, and we saw, I think, a 76 percent reduction in classroom referrals. So we’ve been able to make it that every year since we opened, that every single kid has gotten one of these awesome classes.

By tending to the souls of the adults, we serve the needs and the interests of the students.

|

| Teacher David Ruiz |

|

David Ruiz, who teaches eighth grade English Language Arts and English Language Development, exemplifies VIDA’s culture of innovation, lifelong learning, and engagement for both learners and adults. By pursuing areas of personal interest through electives and other programs, David keeps his passion for learning alive by learning alongside his students. Whether it’s woodworking, coding, or rock and roll, David strives to engage learners and support them to apply what they learn with him to design thinking projects across the curriculum. “Eric asked us to share our passions and things that we’re interested in that could help kids out when they are designing their prototypes. It takes a lot of different skills to design a decent prototype. The kids might be doing coding with me and building cardboard inventions with motors and lights and programming them to do all kinds of neat things. Or they might be building a skateboard and learning how to cut wood. But all of these are skills that we want to see transfer into the design thinking projects they’re taking on. So that’s how we bring in all those fun classes. We do it because we believe in design thinking as a means for problem solving and actually engaging deeply with content. So there’s just a lot of my personal passions that I get to share, and I’m not afraid to be a beginner. I’ve never taken a very deep programming course other than some very basic stuff. But I knew that I had enough interest in it to want to pursue it. I’m not afraid to have rough edges, and I’m not afraid to share my rough edges. But I’m going to continuously seek to improve myself. I’m a lifelong learner, and that’s what I want to convey to my kids.” |

If we look at VIDA’s arc of learning, we have two axes. One is sophistication. One is time. Over time, we want kids to know and use their strengths and interests, building their own personal brand of, “Who am I? What have I done? And what can I do because I did it?” And then, “What do I aspire toward?”

And so that culminates for most of the kids in their eighth grade resume. This is about your life and who you are. If, at the end of the day, this is just school and the resume is not more about their lives and who they are, we have failed. If they put “English 8, I got a C+,” or “I read Tom Sawyer,” then we have failed. The resume is a very visible way of seeing that. It’s a great internal reminder of what you’re working so hard toward and to see what they can do.

See Sample Resumes

Learn More about Transforming Learning in Vista Unified School District

- Students as Stakeholders and Co-Designers - Students are seen as primary stakeholders in Vista Unified School District’s work to transform learning for equity and lifelong success.

- Partnering with Families for Learner Success and Wellbeing - Vista Unified helps families through school, one student at a time. They attribute their success to love and care and, simply, relationships above all.

- Learner-Centered Assessment: Grading for Competency - Redesigning grading systems to be more personalized, equitable, and standards-based is a major undertaking. These educators are working to figure it out.

This article is from the NGLC publication, VIDA for Life: A Q&A with Vista Innovation & Design Academy.

All images courtesy of Vista Innovation & Design Academy, Vista Unified School District.