What We Can Learn from Finland

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Finland carved out its own pragmatic, steady path to extraordinarily high achievement. How did they do it?

What are the lessons the U.S. should take from Finland and its high-performing students? Visit Helsinki, as I did last week, and you will literally step on one such lesson on every other street corner.

The Finns, almost literally, hold hands and move as one.

Finland’s narrative is the remarkable education story of our time. Like the South Koreans and other Asian nations, they are at or near the top of world rankings on PISA. But unlike them, Finnish kids are demonstrating that strong achievement is possible without extreme investments in time and tutoring. (See Amanda Ripley’s book for more.) As a nation, Finland has not obsessed over its schools or its children. It has simply carved out its own pragmatic, steady path to extraordinarily high achievement—at least as measured by PISA. How have they done it?

Judging from what we saw and heard last week, the story of what Finland did can be told fairly simply—and it is an important story for Americans to absorb. Equally important, though, is understanding what the Finns haven’t done—yet.

It would be no more plausible for an army general or business executive to become a district superintendent in Finland than it would be for them to become a surgeon.

The Starting Point: A working system and a workable size

The Finns seem to be wired for pragmatic, purpose-driven pursuit of the social objectives they view as paramount. Their governing system doesn’t zig and zag the way ours does, nor is it too frequently straightjacketed by hardball politics. Said one educator with us on the trip: “The whole week, I had the impression that everyone we talked to, from policymakers and advocacy organizations to principals and teachers, were all on the same page. They all agreed, more or less, on where their schools are and where they need to go.”

This pragmatic approach to politics and policy-making is enabled in part by the size of the Finnish ecosystem—about the GDP of Connecticut in a land mass 4/5 the size of California—and by the relative homogeneity of that populace (though it is beginning to become more diverse).

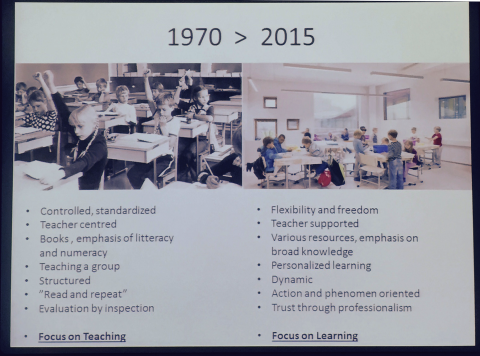

Finland's transition from its 1970s-era system to its current system (from a slide presented by the Finnish ministry of education)

The Crucial Choices

But all of that is essentially true of Norway, next door, which—following an approach to public education somewhat like that of the U.S.—is nobody’s poster-child for excellence in achievement. The Finns have made several crucial choices that appear to have contributed to their results. As a nation, they:

- Committed years ago to a net of social support for its citizens that makes the gap between upper and lower levels among the narrowest in the world. Poverty levels are extremely low; education is completely free, from pre-school through college and for some areas of graduate study, through postgraduate degree programs as well. Their schools do not need to organize themselves to serve the extreme diversity of readiness and out-of-school dysfunction that many American educators must address. (That’s the other poignant message we travelers all read in the handholding streetcorner iconography in Helsinki last week.)

- Deliberately set out to turn teaching into a sought-after profession with all of the attributes of medicine and the law. We Americans wring our hands over this one, but everything we have done over the past twenty years to scale standards-based reform has diminished, not enhanced, teachers’ status and the role they play in shaping the system and learning models in which they work. The Finns, by contrast, eliminated eighty percent of their teacher college programs near the start of their push to improve their schools in the mid-1970s. Teaching became very selective; the remaining nine colleges now admit just one out of ten applicants. Teachers are accorded deep respect as professionals of their practice. Their training focuses on learning science; they are relied upon to conduct research in their classrooms and to collaboratively analyze results. They are not paid substantially more than their American counterparts—but they benefit from the wide range of Finnish social services (and aren’t looking up at vast differences in compensation between them and other professions).

- Developed a system and culture shaped by pervasive trust. When the Finns started their push, their system looked somewhat like ours, with strong, mandated controls on practice and curriculum. (Our controls are the consequence of accountability driven by annual testing.) In the late 1980s, as teachers and schools developed substantially stronger capacity through the reforms of the previous decade, those controls were relaxed. Twenty years later, the nation’s education system is designed, managed, and implemented by the education professionals. It would be no more plausible for an army general or business executive to become a district superintendent in Finland than it would be for them to become a surgeon. Moreover, there are no tests, other than those used for formative purposes in the classroom, until the matriculation exam that all students take at age 16. That test carries consequences, but—as we heard several times last week—there “are no dead ends in the Finnish system,” and students are always able to double back and re-commit toward pathways they decide they want to pursue.

Up to age seven, Finnish children are encouraged to play. Playful learning is the watchword. Maria Montessori and John Dewey would applaud.

What Finland Hasn’t Done—And What’s Next

Many of the American educators I traveled with (our excellent visit was organized by EF Education Tours) remarked to me on what they didn’t see on our trip. That was inventive pedagogy, at least during the years we associate with third grade through twelfth. Up to age seven, Finnish children are encouraged to play. Playful learning is the watchword. Maria Montessori and John Dewey—along with most learning scientists and brain development researchers—would enthusiastically applaud. After that, Finnish classroom practice doesn’t appear to diverge all that much from the same traditional, textbook-driven, teacher-centered, content-delivery approaches that have been the stock in trade of our first century of public schooling. (The Finns do appear to put more emphasis in learning the hard sciences through constant experimenting in the labs.)

The Americans I traveled with generally felt that they are seeing more inventive pedagogy on our side of the pond: more experimenting in school design, deeper levels of engagement around project-based and student-centered learning. Of course, this was a self-selected group of internationally curious educators and their perspectives may not perfectly reflect the norms.

But even this group couldn’t help but wonder whether the Finns will quickly outstrip us in the pedagogical arena, too. In the latest PISA rankings (2012), Finland slipped somewhat in math, particularly in comparison to Asian countries. The nation’s response seems far removed from the clamor for stepped-up accountability we would likely see in the U.S. under such circumstances. Instead, Finland is making a national commitment, in their handholding “all-in” way, to what they call phenomenon-based education—essentially, moving from organizing all learning by subjects towards organizing all learning by topics. They cite climate change as an example. Piloting has been going on for two years, but beginning with the introduction of a new national curriculum in August 2016, students will learn math, literacy, science, social studies, and a range of 21st century skills by exploring real-world phenomena and considering solutions to societal challenges.

An Educational Grand Slam

Once these reforms are established, Finland will have hit the equivalent of a human capital development four-bagger:

- Extensive social welfare supports

- An effective philosophy on all-important early childhood

- An extremely capable corps of teachers who are regarded as top professionals; and

- Active-learning designs for schools and pedagogy that reflect what we now know about how people learn best, and are deliberately aimed at building the skills and dispositions that young adults need in order to thrive in the 21st century.

The Finns generously say they learn quite a bit from us. We are quite good, they say, at generating points of light. Combine the Harlem Children’s Zone, the emerging set of public Montessori schools around the country, and High Tech High (which prepares many of its own teachers through its next gen, accredited teacher college), for example, and you’d have a typically boot-strapped, entrepreneurial, American version of that grand slam. But… enabling most American children to benefit from those approaches would require an ability to make hard choices, uproot traditional structures and operating habits, and learn to practice a high degree of trust throughout our education system.

Can we do that? Americans used to believe we could accomplish just about anything we set our minds to achieve. That’s been a hallmark of our national character. Celebrating this Fourth of July by figuring out how to work our way back to that national mindset might be a good place to start.