The Full Spectrum of Evidence for Student-Centered Learning: Ready for Use, Now!

Topics

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

To help young people develop into high-functioning adults, we need to work with—and value—the full spectrum of evidence that demonstrates their development.

Our nation’s schoolchildren are being strangled in a dense thicket of inconclusive, incomplete, and alarmingly insufficient data. Like an unstoppable jungle of kudzu, the vines of accountability-driven test data have wound their way into every societal structure they meet, from education policymaking and media-reporting at all levels to housing prices and real estate brokering.

These voracious vines feed on our collective hunger for a clear, simple, and definitive answer to a deceptively complex question: What’s working? The answers that our systems, policies, and practices currently value may satisfy our need for simplicity and clarity, but they have led to a dangerously narrow societal understanding of the complex process of human development; a vast ecosystem of money, jobs, and power dedicated to its own reinforcement; and to a public school experience for most children in the U.S. that in no way—as other data tell us so clearly!—adequately prepares them for fulfilling, contributing adult lives in the real world.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Public Education’s Primal Scream

Millions of us, involved somehow in U.S. public education, are crying out: Is there anything out there that is more important than whacking back these strangling vines and fundamentally redoing our accountability system?

If we are ever to change, fundamentally, the learning experience and life trajectory of most or all schoolchildren in this country, we need to change what we’re feeding the kudzu. We need a whole different way of thinking about “what works:” how we define it, how we measure it, and how we use those measurements to catalyze learning environments that foster whole-child growth and academic achievement. With The Full Spectrum of Evidence for Student-Centered Learning, which NGLC is proud to release today, we are offering an important contribution to that new learning approach.

This project, funded by the Leon Lowenstein Foundation, draws on a year’s worth of focused interviews with national leaders in assessment, educators who lead and support student-centered schools, and—most essentially—students. It also draws deeply on NGLC’s six-year involvement in the Assessment for Learning Project. It’s grounded in a decade of partnership with educators creating next gen, student-centered schools, and the full spectrum of measurement strategies they have used to determine “what works” in helping young people develop into high-functioning adults.

Those educators—including those who participated, with some of their students, in this project—are in no way advocating for a retreat from an emphasis on literacy and numeracy. They are not shying away from the use of testing to gauge student progress for formative and summative purposes. They are not backing away from accountability in some revised form. They are the front lines in a practitioner-led movement to align public education’s practices and policies with what learning science and common sense tell us represents the full spectrum, and deep complexity, of human development.

Deeper Learning Requires Broader Evidence

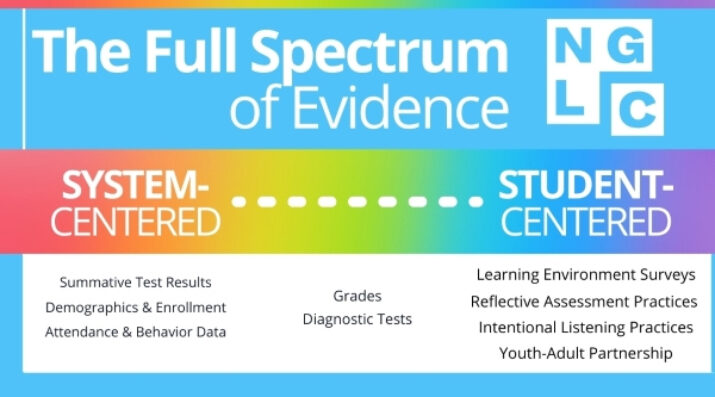

There has been substantial progress over recent decades in understanding the science of learning and development, coupled with reimagined visions for student success—demonstrated by so many communities’ effort to create a new portrait of a graduate. The Full Spectrum project provides a corollary framework to help us grasp the science of productively measuring that learning and development toward those graduate outcomes. At one end, the spectrum encompasses system-centered evidence. This kind of evidence is used primarily to generate, through largely quantitative methods, snapshots of performance in academic skill and knowledge-building, attendance, and behavior. In the center of the spectrum are forms of evidence-gathering that draw on a range of inputs and are used for both summative and formative purposes.

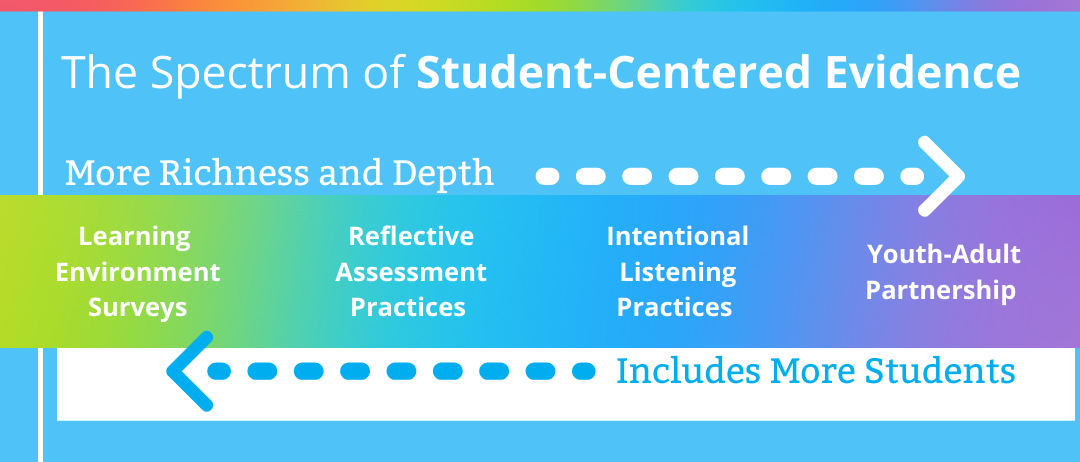

At the other end of the spectrum is student-centered evidence, the focus of the Lowenstein Foundation’s grant to NGLC. This end of the spectrum is itself a continuum of four forms of evidence-gathering that place increasing emphasis on the student role.

At www.studentcenteredevidence.org, you will find descriptions of these evidence-gathering practices, a deep discussion of their validity and reliability, and recommendations from NGLC’s network of next gen educators on how to develop student-centered evidence-gathering practices in schools and districts and apply them to make informed decisions. “Testing data tell us some important things,” we kept hearing from participating educators, “but we rely on student-centered evidence to make the data meaningful, and to help us as well as our leadership and governing boards make good, student-centered choices.”

At the website, you’ll also find an extensive gallery of audio files—examples of student reflections on their own learning, a central attribute of measurement at the student-centered end of the Full Spectrum. Highlighting student voice and exploring the active student role in gathering and using evidence of learning was a primary focus of the Full Spectrum project. Here is just one example from the gallery of a student from Tulsa Public Schools (Oklahoma) reflecting on peer feedback:

The site also suggests resources for deeper probing into other forms of student-centered evidence, including surveys and performance-based assessment.

You Can Help “Full Spectrum” Transform Public Education

Our goals for this project are ambitious. They are attainable only with your help—you and thousands of others who might read this blog post, explore the site, and begin using the #fullspectrum metaphor almost immediately. Please join us!

- In classrooms and schools’ approaches to learning: We envision educators and students working together to develop and deepen student-centered evidence-gathering practices and mindsets.

- In school districts and school board decision-making: We envision ed leaders making choices based on evidence and data from across the full spectrum of evidence-gathering strategies.

- In research, provider, funder, and ed-reform advocate circles: We envision the value and importance of the full spectrum of evidence embraced as an imperative for whole-child, deeper, student-centered learning. We also envision the immediate expansion of investment in developing the student-centered end of that spectrum as a balance to the prevailing over-emphasis on the system-centered end.

- In state and federal policy-maker circles: We envision greater recognition of the crucial role of student-centered evidence in local decision-making—and firm understanding that, for the most part, it is inappropriate to use student-centered evidence in current-generation state-run accountability systems that tend to produce “gaming,” compliance mindsets, and constrained practice.

Increasingly, as schools and communities oh-so-gradually emerge from COVID, they are focusing on a broader spectrum of developmental attributes and competencies among the students they serve: proficiency in core academic areas for sure, but also students’ emotional well-being, along with deepening capacities for self-direction, resilience, creative problem-solving, collaboration, and communicating in numerous forms. This promising movement will fail if it is not accompanied by a corresponding commitment to exploring, and using, the full spectrum of evidence of student growth across these competencies—including the active participation and reflections of the learners themselves.

To learn more about the Full Spectrum of Evidence and to listen to more student voices, visit www.studentcenteredevidence.org.