Experiential Learning about Race

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

An educator from Oakland Unified School District shares why he is passionate about experiential learning that is both rigorously intellectual and profoundly moving, especially when students learn about race and racism.

I still remember my first and only time dunking a basketball. We were in the high school gym and one of the high school players looked at our class of 2nd graders and asked who the strongest kid was. Suddenly, all eyes were on me. In the next moment, I’m on this guy’s shoulders hoisting the ball over my head and then SLAM!

...the ball ricocheted off the rim. On my second take, it’s a dunk.

I never became a basketball star. What’s most memorable about my slam dunk is that the other kids in my class, most of whom were white, thought that I, one of the few Asian American boys, was strong. My later experience of my race in middle and high school perpetuated a different set of beliefs. I wasn’t strong; I was alien, invisible, and weak.

I had this nagging sense that I did not belong. At times, it was overt discrimination. Kids made fun of what I ate and what my house smelled like. Even my friends would use slurs about my “chinky” eyes, taunt me with fake karate chops, and mock my family’s language with their imitation “ching chong” sounds.

Over the years, I blamed myself for these experiences. Race was always in the air, but I was not able to explain that my experience of alienation was part of a long history of racism in this country.

It wasn’t until I went to college that I had an insight that would change my life.

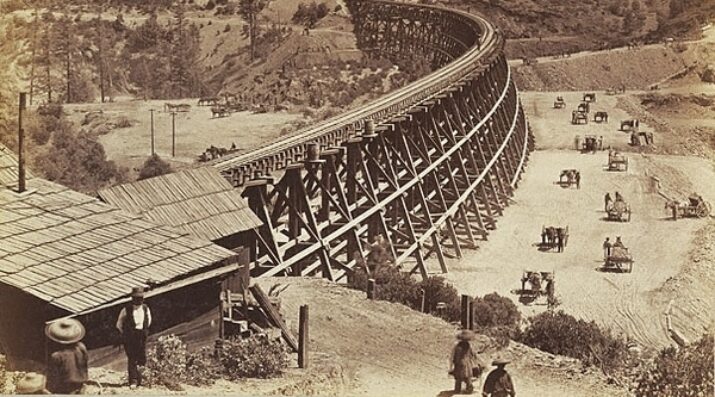

A community organizer from New York City Chinatown showed us images of Chinese railroad workers. My mind was ablaze. Chinese immigrants had helped build a railway system that would be crucial to the industrial revolution and the growth of the American empire? How could I have been kept in the dark for so many years?

And then he showed us the racist caricatures. The darkened skin. Exaggerated overbites and slanted eyes. I saw the line connecting those political cartoons of Chinese workers in the 1870s to the playground taunts of my Korean American childhood.

You might think I would be mad. And I was. But I also experienced a moment of freedom.

My ignorance had been like my own version of the dark ages. Knowledge of this history was the dawn of a new age. Instead of blaming myself, I could see that my experience fit within a history of racist treatment of people of color. I could see how the history I was taught in schools was cleansed of the essential contributions of people of color. The hateful treatment of those groups was also erased, leaving a sanitized version of history that reinforced the centrality and goodness of white people.

I committed myself to become an educator who taught about the role people of color play in the shaping of this country. I believed that these historical truths would inoculate students of color against the shame and inferiority perpetuated by the scourge of racism.

What could this kind of education look like? It would be both rigorously intellectual and profoundly moving.

I experienced intellectual challenge myself, such as when my senior year high school teacher had us read historical documents about slavery and analyze them to better understand the experience of enslaved Africans. But, my history teacher never took us a few miles from the school campus to one of the largest slave pens in the country. We never visited the homes of Quakers who were suspected to be conductors on the Underground Railroad. These are two of the numerous sites that are included in a walking tour of black history in Alexandria, which I did not know existed until I visited the Alexandria Black History Museum in my 20s.

Alexandria is not unique when it comes to historic sites related to race where students can go beyond learning the facts of history; they can feel the emotional weight of that history.

If you teach near New Orleans, you can take students to a memorial to the 350 enslaved people at the Whitney Plantation. Walking into the original slave cabins and reflecting in silence on the 1811 slave revolt gives a window into slavery that no textbook can achieve. From Salt Lake City, it’s just a 90 minute drive to see where the transcontinental railroad was connected, a herculean effort shouldered largely by Chinese and Irish workers. And, for those who teach near San Francisco State University, they can bring their classes to learn about the longest student strike in American history that led to this country’s first and only Ethnic Studies College.

With each foot step and inhalation of air, students connect to others who have walked, breathed, and made their lives in these places. These visceral experiences challenge students to ask themselves where they belong and reflect on their purpose in the world. Teaching in this manner requires thoughtful preparation (see resources), and the reward is that students of all backgrounds have a more nuanced and empathic understanding of race and our shared history as Americans.

James Baldwin, in a speech to teachers in 1963, gave this advice:

I would try to make him [the Negro child] know that just as American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it, so is the world larger, more daring, more beautiful, and more terrible, but principally larger—and that it belongs to him.

Baldwin was writing on behalf of black children, but his advice is salient to the education of all children, particularly to those who have been ignored, pushed to the margins, or tokenized in how we teach history. It would have helped me—an Asian American kid—understand that true strength does not come from dunking a basketball, but it comes from knowing deep inside that I belong in this world.

Photo at top: Trestle on Central Pacific Railroad, by Carleton E. Watkins; public domain.