Now is the Time to Activate Teachers as Leaders and Change Agents

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Schools are trying out distributed leadership during the pandemic and existing power dynamics have started to shift with the culture of shared authority and trusting relationships.

How can our education systems and operating habits best enable next generation learning, rather than obstruct and diminish it?

It was with this question in mind that NGLC’s Transformation Design project began. Starting in October 2018, with funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, NGLC invited a team of leaders from innovative districts and leading experts in educational change to answer this question. Since then the project team has worked together to identify, synthesize, and disseminate effective change strategies for schools and school districts moving toward next generation learning and school redesign.

As my colleague Kristen Vogt explains in her blog post “How K-12 Can Start Now to Transform the Future,” Transformation Design is not a crisis response strategy to address the COVID-19 pandemic or trauma associated with systemic racism. Rather, “Transformation Design is a longer-term change strategy that’s focused on culture and systems.” However, learning communities can intentionally use Transformation Design practices right now as they create solutions for the pressing needs and challenges that their districts are working to solve at this moment.

Transformation Design recognizes that a district’s greatest asset is the people who make up the system. Not surprisingly, then, many of the Transformation Design cultural practices involve building leadership capacity and distributing leadership throughout the learning community.

For example, in some schools and districts in the NGLC network, responding to current crises is accelerating and deepening their commitment to a distributed approach to leadership. What may have begun as a necessity to cope with the overwhelming workload of planning for the 2020-2021 school year has inspired a new culture of shared authority and trusting relationships. Existing power dynamics have started to shift, and the people closest to the change have become empowered to take action.

This edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning focuses on Mohawk Trail Regional School (MTRS) in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts. Even before the pandemic, Distributed Leadership was a cornerstone of MTRS’s Trailblazer Model, a new vision for relevant and meaningful education, learner success in the 21st century, and creating a culture of shared ownership and agency among students and adults. I spoke to leaders—both positional and emerging—about how meeting the challenges of this year has built on and strengthened their Distributed Leadership approach. In particular, we discussed:

- How MTRS is cultivating practices and mindsets for Distributed Leadership

- Ways teachers are exercising leadership in professional learning

Building Culture and Practice in Tandem

A general theme I’ve seen this year is that having to do school differently is encouraging people to take more risks and be vulnerable to grow their practice, and that’s been positive. [District] admin doesn’t need to be a part of every little thing—there are so many leaders taking ownership at the building level.

—Sarah Jetzon, director of curriculum & instruction, Mohawk Trail/Hawlemont Regional School Districts

Long before the pandemic and resulting school closures made distributing leadership a practical necessity, MTRS leaders were already developing their own capacity around this practice and had created or redefined a number of structures to support it. For example, as principal Marisa Mendonsa points out, teachers were leading task forces to support key elements of MTRS’s transformation to a whole-person approach inspired by NGLC’s MyWays Student Success Framework. According to Marisa, these teacher-led task forces were designing an Advisory program, piloting student-led portfolios, and reimagining the master schedule. In addition, the Instructional Leadership Team (ILT), a longstanding body of teacher-leaders representing different subject areas, was activated to support their peers’ classroom practices and learning designs aligned to the new vision of success.

What Marisa and other MTRS leaders see as new, however, is an emerging culture of both empowerment and vulnerability. With the pandemic requiring beginning and veteran teachers alike to come up with new ways to teach, Marisa notes, “Newness is an asset. People are willing to throw emails out with resources, tools, and strategies, and I see evidence of people sharing back with comments like, ‘I used it, too,’ or ‘it worked for me in this way.’ There’s a new culture of freedom and sharing. Teachers are feeling empowered to develop and share things out without checking in with admin. That is new this year.”

She also observes that, as the admin team lets the constant check-in kinds of traditional authority go and gets out of the way to enable others to lead, “People really have a sense of owning this work and are getting into the groove of work groups and task forces.”

While Marisa acknowledges that risk-taking is still a growth area for teachers, Diane Zamer, the assistant principal at MTRS, notes that professional learning related to technology is one area in which teachers have felt more comfortable not being experts. When it comes to using new technology tools to support remote learning, she says, “Teachers are demonstrating asking for help when they need it and being vulnerable to get that help. It’s been nice to see teachers step into the tech leader piece. How might we leverage this disposition and transfer what’s happening in tech to other spheres?” she wonders.

Leveraging Distributed Expertise

I have a lot of pride in our district for Distributed Leadership and offering flexibility in professional learning. In other districts, teachers are told what to do every moment, and they have no choices. I feel very lucky. Our district is doing a fantastic job of making teachers responsible for their own learning, which is what we want our students to be learning to do.

—Emily Willis, MTRS librarian and digital literacy specialist

At its core, Distributed Leadership invites and supports those closest to the work—the ones with the greatest stake in the outcomes—to make decisions, create conditions for success, and own the aspects of learning that materially affect their work. In a school or district that has embraced Distributed Leadership, opportunities to lead abound, and all members of the community are empowered to take action based on skills, expertise, commitment to the vision, and willingness to engage in the challenging work to bring it about.

One example of this kind of leadership based on expertise is Emily’s new role as a digital literacy specialist for the district. When the pandemic closed schools for in-person learning, teachers clamored for support in using technology for virtual learning. At around the same time, Emily’s position as a school librarian at MTRS was slated to be reduced due to budget cuts. However, as she explains, “Marisa and I talked about the need for teacher support with digital tools, something that I had always done, but not formally. She asked me what I could foresee my role being to meet teachers’ needs. It made a lot of sense for me to serve as a tech support person for teachers throughout the district.”

A recent professional learning day at MTRS illustrates what activating leaders based on their skill and will—and note solely on traditional leadership roles—can look like in practice. The in-service day, held on October 30, for example, was a hybrid event, with more traditional workshops to support district initiatives in the morning and teacher-led technology sessions in the afternoon. In partnership with school leaders, Emily and a group of volunteer teachers created and facilitated sessions on using technology that were based on their individual areas of expertise. As Sarah describes, “We tried to create a good balance of targeted and role-specific learning opportunities that would be meaningful to educators, would draw upon educator expertise, and would give choice.”

According to Emily, the idea for the teacher-led professional learning event arose from an expressed need around remote learning. “I was getting a lot of feedback that teachers needed tech PD. They felt they had some practice with a few tools, but they wanted to increase their repertoire. In order to maximize the choices, Sarah, Diane, and I thought it would make sense to find out if some teachers felt particularly confident about certain tools and would be willing to lead a training.”

Originally, Emily and other MTRS leaders’ plans for the afternoon were modest: “We came up with a list of teachers who might be able to co-lead a session,” she recalls, “or maybe facilitate a conversation and share tips with a group of colleagues. I thought that would be a good way to take out some of the risk. Less stressful than leading a formal tech training, or it would be for me.”

The response to Emily’s call for volunteers, however, far surpassed her expectations. So many educators stepped up to lead, she reports, that the resulting event was able to offer dozens of options in three strands: formal workshops, collegial conversations and unconferences, and self-directed webinars. Topics included using tools like Edpuzzle, Parlay, Google Slides, Kahoot, and Jamboard, as well as supporting classroom practices like class discussions and small-group instruction in a virtual environment. One session, led by a paraprofessional, shared best practices for that role in a remote learning context.

Even teachers who had never provided professional learning to colleagues before answered the call. As Emily notes, “We have more teachers who are willing to take risks. That’s happening a lot right now.” As for her own experience as a leader of the professional learning event, Emily gives credit to Marisa, Sarah, and Diane. “They are very supportive. I feel comfortable going to them with anything—I don’t feel they are judging me. I hope everyone is feeling that way, too.”

Trusting Educators to Lead

I really appreciated this PD day. There are so many things going on in the classroom—so much amazing brain power on our staff. They know our district, they know our students. There was no need to go outside of staff. I hope we can come out of this [pandemic] and maintain what we learned that was good.

—Rachel Hoogstraten, MTRS high school English teacher

When she first heard about the opportunity to lead a professional learning session, Rachel recalls her immediate and positive reaction: “I saw Emily’s email to faculty about the PD day and that she was looking for volunteers to lead a workshop. I thought, ‘What have I been doing? Do I have something I can share?’”

To design the workshop, Rachel drew on a “digital scrapbook” activity with Google Slides she had originally developed for “Artglish,” an integrated Arts and English course. As Rachel explains, each slide captured a unique quotation from 1968, the year the graphic memoir learners were reading was set. “Each kid was in charge of finding out what that quote meant, as well as curating information and visuals” that, when taken together, could build the historical context. “Then they looked at each others’ pages, adding comments, questions, and connections they were making. The ability to give feedback really upped the game.”

Having successfully used the same activity in multiple classes, Rachel realized, “[the digital scrapbook] was customizable for all subjects and grades” and therefore had potential value as a topic for the professional learning day. According to Rachel, participants in the workshop had the opportunity to explore her examples, create model slides for their own courses, and comment on how their peers had customized the activity for learners from elementary history to AP English classes. “I learned a lot myself,” Rachel says. “It was great to see what everyone came up with.”

To Rachel what was also significant about the teacher-led professional learning was the message it sent to teachers. “I felt trusted to do the PD and not have someone looking over my shoulder.” As explained in “Distribute Leadership,” one of the Transformation Design Deep Dive Guides, distributing leadership is a key practice for building a foundation of trust and thereby creating an environment supportive of change.

Rachel explains her experience of the teacher-led event this way: “I really appreciated the independent choice for that afternoon, the ability for teachers to choose options that were relevant to the moment. It shows us that the admin team trusts us to use our time well and knows that we are always looking to improve. I think it’s important to name that.”

Resources:

- Distributive Leadership in Practice. This 3½-minute video conveys how teacher-leaders in the Kettle Moraine School District in Wisconsin are empowered to lead innovative efforts in the district.

- An extension of the Transformation Design District Self-Assessment, the Distribute Leadership Deep Dive Guide is designed to help teams shift from reflection to bold, deliberate action that accelerates progress in their districtwide learning transformation.

- Teacher-led sessions for the MTRS October 30 in-service included these remote learning collegial discussions and these tech workshops. A third opt-in learning strand enabled teachers to choose self-guided learning from this collection of webinars and other resources on topics like student engagement, equity, and social-emotional learning in a remote environment, as well as on technology tools.

- After the professional learning event, Emily used this survey to solicit feedback from teachers on the three types of sessions.

- This model of a literature-based digital scrapbook was used in Rachel's Global Perspectives class for 11th and 12th grade learners and shared with peers during her workshop.

- To learn more about how educators can lead the change to design transformational and equitable schools, explore the toolkits and other resources at TrueSchool.

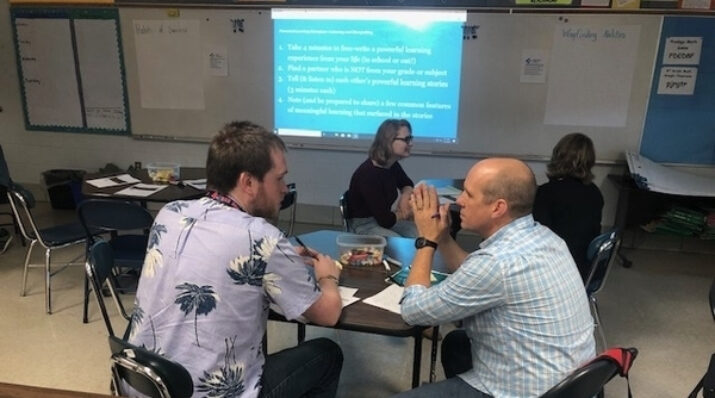

Photo at top of Mohawk Trail teachers by Stefanie Blouin.