Start Strong with a New Teacher Mindset to Transform Your Classroom

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

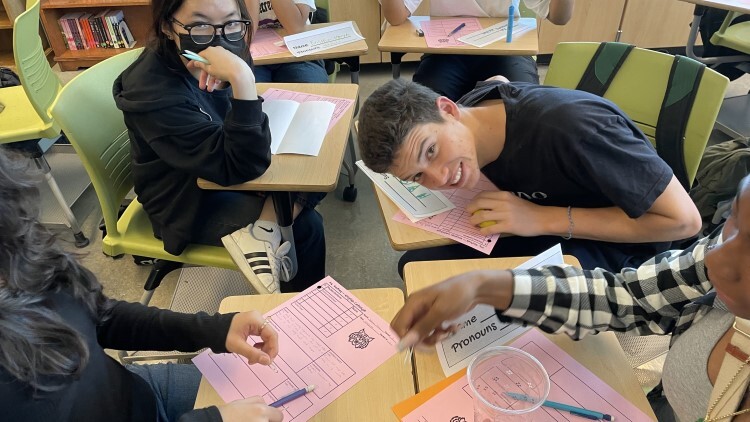

To transform classrooms into collaborative learning spaces, teachers can remind themselves that young people are capable of more than we think and ask themselves what they are doing that students could do instead.

The Beginning of the Year

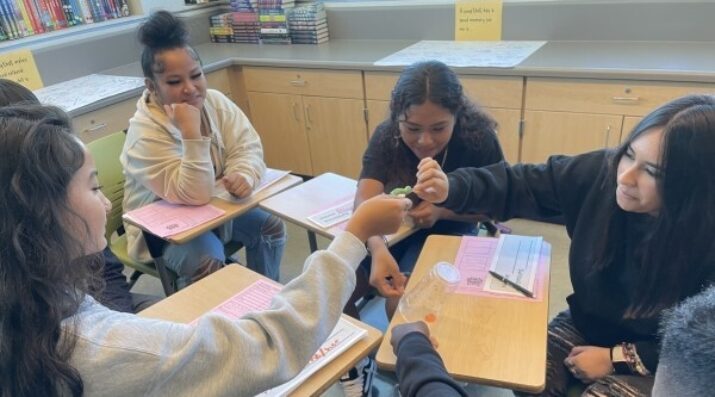

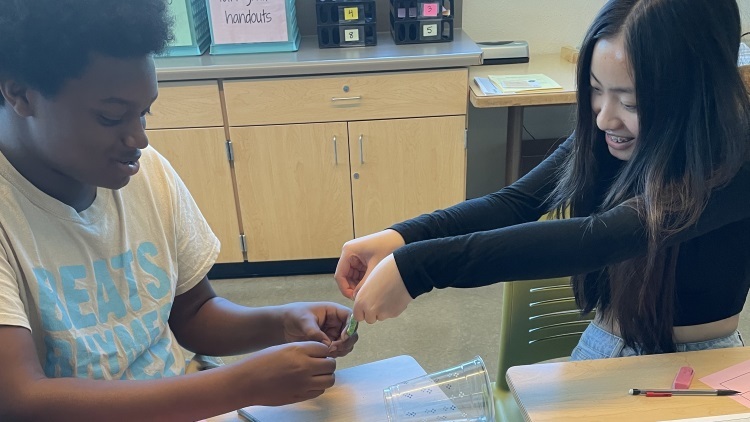

It’s early in Jessica’s second week back teaching, and we’re sitting after dinner quietly in the living room, talking about what happens in the first weeks of school each year. Jessica is my wife and teaches in the Public Health Academy at Oakland High School in Oakland, California. Today a woman who works in the district supporting newer teachers came by and asked if she could sit in on one of Jessica’s classes, just to see how Jessica was designing the first few weeks. Jessica’s students were clustered in small groups, standing or sitting, hunched over their computers, a handout in hand with several questions on it. They were busily engaged in a “syllabus scavenger hunt.” Each team was scanning through Jessica’s syllabus on Google Classroom, looking for the answers to the questions on their handout. Afterwards, they reported out their findings, and a lively conversation about the year’s plan unfolded. The visitor was clearly pleased, but then said, “Oh, if only I had known about this activity just a few hours ago! I just watched a new teacher spend the whole period reading her whole syllabus out loud to a classroom filled with zoned out, disengaged teenagers. This would have made all the difference. What you do is magical!”

Jessica matter of factly assured me that evening that what she did was in no way magical, but it did accomplish several things. First of all it got the students working on something, and doing it collaboratively, engaging in conversation with each other, focusing on a task that everyone in the class could do. Often the first weeks in a new class are a little awkward, as kids check each other out, trying to figure out the patterns of friendships and clusters of kids like them and not like them, building new relationships, and settling into the space slowly and tentatively. Activities like this get them connected to each other, and moving into and around the space and making it their own, not a foreign country that belongs to the teacher that they just visit once in a while. These activities are also low stakes, but they teach processes that will become embedded in the classroom routines and rituals, establish the classroom learning culture, and provide the foundations for higher risk academic activities later on. And in this case, they preshadow the work of the year, in ways that get the students curious, but also establish through the students’ actual experience some norms and procedures that are the policies for how her classroom operates. Finally, they allow Jessica to move around the classroom herself, and watch and talk with her students individually, getting to know who they are and how they work.

I was reminded of an English teacher whose classroom I had sat in a few years ago. He was introducing the class to The Crucible. The play has a rather large cast of characters, and their relations among each other are fairly complex. He had found photos of the actors who played each of the characters in the movie version and made slides of them with their bio and relations to other characters listed below each photo. Standing at the front of the classroom, he masterfully and animatedly read through each slide, clearly excited himself to be sharing this with the class in preparation for their reading the play. He was quite entertaining! He had also created an activity for the students where, as he spoke, each student sitting at their own desk drew a sort of sociogram of the interrelations of the characters. Students were quiet and paying attention. There was a level of engagement as they listened and drew their maps.

But I found myself thinking afterwards, what if instead of him doing all that excited talking, the students were the ones doing the talking? What if he did the introduction to The Crucible as a Tea Party activity, where each student had a card with one of the characters’ names and the short bio and description of that character’s relation to the others? What if they mingled throughout the room with their card and an “interview sheet”—another sheet of paper with the list of other characters—and “met” and had a brief conversation with the students representing each of the other characters, which they would record on their interview sheet? And then what if they had a class conversation—or a small group conversation first, followed by a whole class conversation—about what they had discovered about the characters, and what that might then predict about what the play was about?

Two Ways of Thinking to Transform Your Classroom

There are several differences apparent here between these scenarios. I think of them as mantras for good teaching.

- The first is a statement: Young people are always capable of much more than we think they are.

- The second is a reminder, to regularly ask yourself: What is something I am doing that could be designed so the students are doing it instead of me?

The second might be the easiest question a teacher could ask themselves to transform their classroom into a collaborative learning space and culture. Sure, it takes a little giving up of control, which can be a scary thing to do—you never know what might emerge! But these ideas are in service to greater engagement, hence, learning.

Also, it takes a certain amount of creativity to come up with these activities, but as Jessica tells me, she doesn’t make most of these up; every time she meets another teacher, she learns some kind of new activity that fits somewhere in her curriculum. You can become a networking innovator, like a honey bee, gathering new ideas everywhere you go (paralleling the way you want your students to be gathering new ideas everywhere they go, in your classroom and beyond).

But we’re not just talking about a couple of good moves a teacher might make. So, let’s take a step back and consider some theoretical underpinnings of these two “mantras.”

Six-Word Memoir collage posters

Theoretical Underpinnings

At first it might seem like these are just principles of good classroom management, and surely they are in some way. Some of the earliest work on “cooperative learning” strategies was billed as being in service of classroom management. Students who are doing something together within the constraints of a designed structure are more likely to be on task and at least somewhat present. The teacher maintains control over the classroom as a calm space for knowledge transmission. In the classroom of the new teacher who was reading her syllabus aloud to her students, there was very little happening to either manage the class or to engage the class. Students were not doing anything. The only constraint was the unspoken expectation that the students would be docile and compliant while the teacher was talking. That’s a formula for trouble down the line.

In the example with The Crucible, the students were doing something, and the class was calm and quiet, and students were paying attention. It just wasn’t a particularly high level of engagement or attention. The teacher was doing all the heavy lifting. The students were being entertained.

In the syllabus scavenger hunt example (and the Tea Party example), while the conceptual content was not particularly challenging (the syllabus example is designed to be an early in the year activity), the experience that the students were engaged in was teaching them a lot about classroom routines and expectations, collaboration, and communication, that is, learning culture. The content was building curiosity about the coming year. And there is a learning theory at play, a social constructivist learning theory: Students learn more when they are actively engaged together in interacting with content, making it their own, grappling with it, “creating knowledge rather than receiving content,” as Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine describe in their book, In Search of Deeper Learning. When it is the students doing the work, it is the students who are doing the learning. And they are capable of doing that.

Jean Piaget put it this way:

“I think that human knowledge is essentially active. To know is to assimilate reality into systems of transformations. To know is to transform reality in order to understand how a certain state is brought about. By virtue of this point of view, I find myself opposed to the view of knowledge as a copy, a passive copy of reality… To my way of thinking, knowing an object does not mean copying it—it means acting upon it… Knowledge, then, is a system of transformations that become progressively adequate… [Knowledge] is drawn not from the object that is acted upon, but from the action itself.”

In the scavenger hunt and tea party, students are interacting with the “object” (the syllabus, the play’s characters) to really know it, to be able to use it. But something else is also happening. Beyond Piaget’s ideas of learning as an interactive, constructivist process, Lev Vygotsky proposed that dialogue with other children and adults is an essential activity for learning. As Vygotsky says, “[l]anguage plays a critical role in cognitive development, progressing from social speech to private speech and finally to inner speech,” (Saul McLeod). So Piaget established that learning is a constructivist process and Vygotsky established that it occurs in social interactions. If students are sitting passively listening to a teacher, they are neither actively engaged in transforming the world to understand it, nor are they engaged in social interaction, in dialogue with others in the process of developing their own “inner speech,” or knowledge.

By guiding students to engage with each other to grapple with ideas in ways that establish routines and rituals of learning together, you are creating the conditions of learning and the experiences of learning that build the habits of a classroom culture of learning. Your job is not just to help your students learn what your course content is; it is to help them develop the capacity to learn, and to do that, they need to interact with the “objects” of learning (that is, the world) and they need to interact with each other. This is a cognitive and social constructivist view of learning and knowledge creation; it is not a transmission view of learning. Classroom learning culture is a web of interactions among all your students, with you as the guide and the web-weaver. It is dynamic and complex, and often unpredictable (even as you structure and constrain and scaffold the interactions), as dynamic, complex, and unpredictable as are the individual, and developing, identities of your students.

Weaving the Classroom Learning Culture

So let’s get back to these mantras about students and learning, and about the beginning of the school year: Say to yourself, Young people are always capable of much more than we think they are. And, ask yourself, What is something I am doing that could be designed so the students are doing it instead of me? Students need to be actively engaged in their learning, and doing it in ways that involve them interacting with other students in the classroom. They have the capacity to do that, but often we have acculturated it out of them through years of requiring them to be passive, compliant, and therefore disengaged.

So we have to start with small steps and build from there. Activities that involve interactions with other students with low cognitive load (low stakes) create pathways back into engagement that enable everyone to be successful. These activities also build social learning capacity and contribute to weaving the web of the routines, rituals, and habits of a classroom culture of learning. And they create curiosity and energy in the classroom. Start there. The momentum, the energy, and the capacity and curiosity to learn will grow.

Need Some Ideas?

Besides asking every teacher you meet for things they do, there are two books I’ve found that are truly fantastic in describing how to create engaged classrooms. They are not available from the original organization anymore (it’s no longer active), but I bet you can find them.

- Engaged Classrooms: The Art and Craft of Reaching and Teaching All Learners, Miller-Lieber et al.

- Activators: Classroom Strategies for Engaging Middle and High School Students, Frazier & Miehle. Engaging Schools, publisher.

All photos courtesy of Jessica Forbes.