The Importance of Real-World Learning for Students

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Preparing young people for life-long success through real-world learning

All students need to leave school—frequently, regularly, and of course, temporarily… To accomplish this, schools must take down the walls that separate the learning that students do, and could do, in school from the learning they do and could do, outside.

—Elliot Washor and Charles Mojkowski, Big Picture Learning

In 2017 NGLC published the MyWays Student Success Series, a collection of reports, resources, and tools to support educators and communities to reimagine traditional definitions of learner success and redesign learning to help all students prepare for their futures. Inspired by the practices and valuable feedback from schools and districts in the NGLC network, the MyWays project has continued to evolve and expand to meet the needs of practitioners and their communities.

One area of particular interest for educators who are adopting broader definitions of success, like the MyWays Student Success Framework, is providing all students with authentic, real-world learning opportunities. Grace Belfiore, one of the principal researchers and authors of the MyWays report series, observes that, “One of the most striking implications of the MyWays’ research was the realization that it is difficult, if not impossible, to help learners develop these competencies and skills without going outside the classroom walls.” She also notes that, although some educators in the NGLC community have made real-world learning the cornerstone of their model, many others who have embraced next gen learning are newcomers to accessing the world outside of school as a rich source of student learning.

School lasts for 12 years, but students’ lives last a lot longer. What are we doing to develop people?

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I spoke to a variety of experts who are partnering with their communities to provide relevant and authentic student learning. This edition will also introduce practitioners to a new NGLC resource for this work, the MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit. In particular, I’ll share:

- Why real-world learning is essential for student success

- Expert advice and resources to incorporate real-world learning in your classroom or school

Skills and Abilities for Lifelong Success

Early access to real-world projects is a springboard to seeing what success looks like outside of the classroom.

—Natasha Morrison, director of real world learning at Da Vinci Schools.

The MyWays Student Success Framework and other 21st-century definitions of success share a fundamental understanding that the world has changed and continues to change at an accelerating rate. In addition to Content Knowledge, learners also need competencies within the MyWays domains of Habits of Success, Creative Know How, and Wayfinding Abilities to navigate through learning, career, and life. Young people need to experience learning that does more than prepare them to take a test or pass into the next grade.

Lindsey Stutheit, workforce partnership liaison at Laramie County School District #1 in Cheyenne, WY, expresses it this way: “For a long time, college- and career-readiness has really meant college, and that, in my experience, has meant preparing for the ACT or other state-mandated standardized tests. We spend a lot of resources and time preparing students for these tests, something fleeting and momentary. These tests are valid measures, but they aren’t geared around careers, personal skills, or adult skills.” Lindsey and other leaders in her district recognize that young people need to develop capabilities that are life-long, life-wide, and life-worthy. “School lasts for 12 years,” she notes, “but students’ lives last a lot longer. What are we doing to develop people?”

Casey Lamb, chief operating officer at Schools That Can, a network of schools that have embraced real-world learning, also argues for a more holistic notion of education and preparation. Real-world learning is, she says, “not just about the partnerships but about the outcomes, which move beyond what is usually tested in schools. It’s about developing whole humans.”

However, expecting schools to do this work alone, our experts tell us, is neither reasonable nor possible. According to Casey, one reason young people need access to learning experiences outside of school is that “the majority of teachers went to school to be teachers. They should not be expected to know everything about all of the myriad fields in order to prepare students for every career and opportunity. Real-world learning connects both students and teachers to people in the community who are working in different environments and have different perspectives, as well as to the skills adults use on a daily basis.”

In this way, Casey explains, real-world experiences “ground students’ learning in the paths they will pursue after graduation. It better prepares them for those pathways, offers them choices, and gives them the ability to be successful there.”

Equitable Access to the World of Adults

Offering opportunities for young people to connect with the world outside of school is not new. Common activities like field trips, science fairs, model UN, theater productions, and extracurricular clubs can provide learners with access to adults in the community. Yet, as Lindsey observes, supporting young people to work side by side with adult professionals “is often teacher dependent and based on the connections individual teachers have. You also see the same students participating over and over.”

According to Lindsey, schools need to ensure that all students have access to support for wayfinding through education, work, and life, including meaningful connections to a wide range of adults from different industries and careers. This kind of social capital “is an equity issue for us and one reason it’s facilitated at the district level—to improve student exposure and reach.”

As described in MyWays Report 4: 5 Essentials in Building Social Capital, social capital is a developmental system of human relationships, including caring adults, mentors and coaches, and professional networks. According to the MyWays research, social capital plays two important roles in the life of young people: “as support in times of need and as social leverage to get ahead.” Significant disparities exist, however, between students of varying socioeconomic backgrounds in the opportunities to build social capital. Because both social capital roles are manifested in well-designed real-world learning, the MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit includes a Social Capital Tool, which supports educators to design learning for social capital benefits for learners across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Real-World Contexts for “Whitewater Learning”

Real-world learning shares characteristics and benefits with other types of authentic, active learning. For example, both school-based and real-world projects can help learners develop Habits of Success, from initiative and perseverance to time management. However, real-world learning also provides the unique benefits, motivations, and opportunities of tackling real problems in the environments in which they occur, in all their messiness and urgency. As explored in the MyWays Key Elements of Real-World Learning Tool, well-designed outside-of-school experiences give learners the opportunity to encounter and respond to “whitewater conditions”—diverse challenges, complexities, and unfamiliar circumstances like those they will encounter as adults.

Skills like project management, collaboration, and problem-solving must be learned in a hands-on, high-stakes way.

Natasha explains that classroom experiences that simulate real-world learning are not enough, especially when it comes to preparing young people for future careers. “You can’t simulate social interaction. It’s not the same as an airline pilot using a flight simulator. There’s no substitute for engagement with the professional world. Attempting to develop career skills with virtually no real-world practice or feedback doesn’t achieve ideal outcomes. Partnership with industry professionals on real-world projects allows students to hone the skills they’ll actually use in the modern workforce. Skills like project management, collaboration, and problem-solving must be learned in a hands-on, high-stakes way.”

In addition to teaching a fuller range of competencies and facilitating connections to a wide array of adults, meaningful real-world learning provides learners with opportunities to make choices and practice self-direction. According to Grace, “Experience in real and diverse situations is key to agency, and to help achieve growth, educators and youth advocates need to help students access and utilize a range of real-world situations.” Real-world learning can also foster identity development, she says, offering young people a vision of what’s possible for their futures.

Connections to the Wider Learning Ecosystem

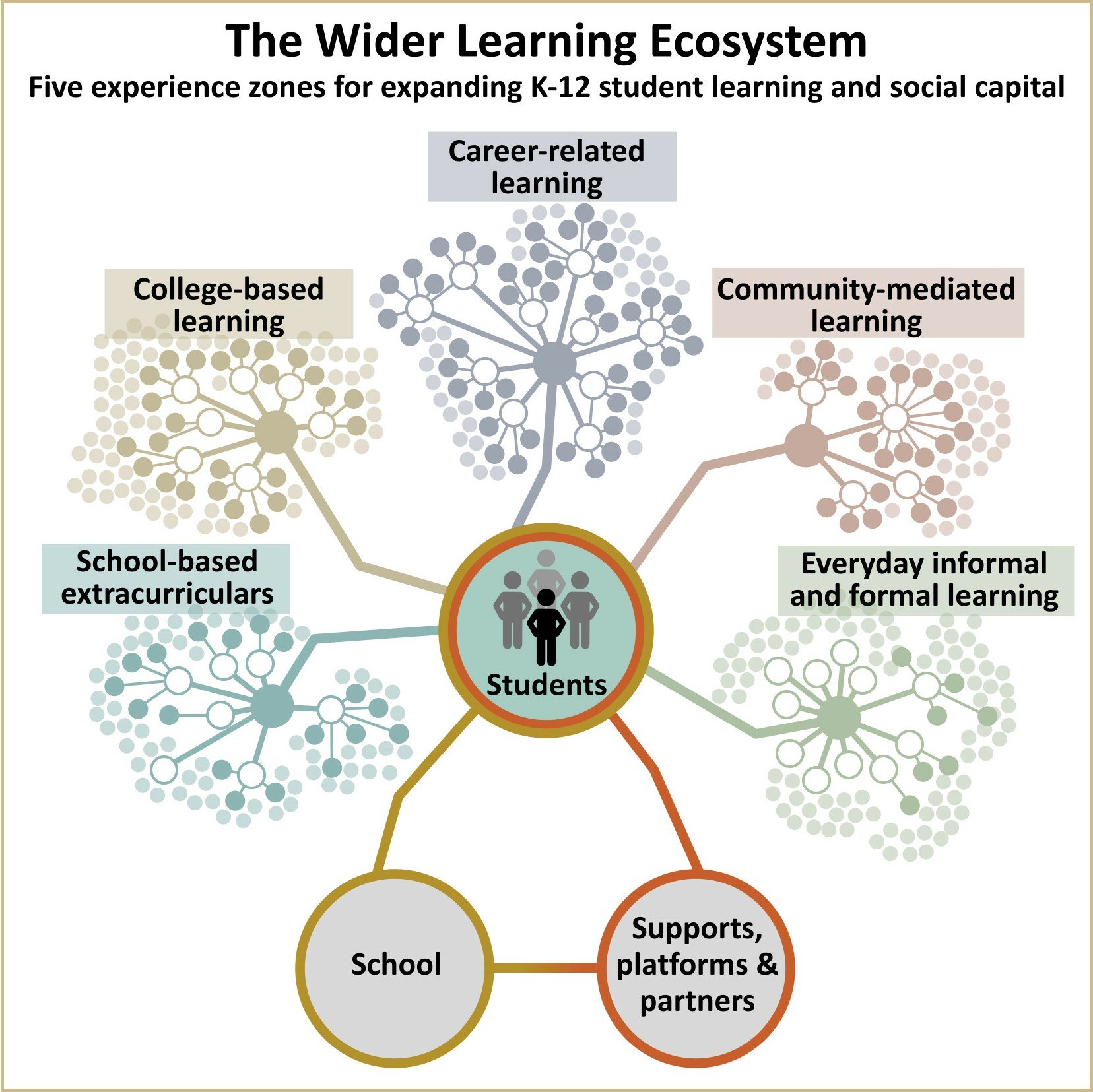

Redesigning learning to be more like an apprenticeship for adult life can seem overwhelming. In part, that’s because educators have traditionally shouldered so much of this responsibility. However, schools and educators have numerous assets and partners for this work. Accessing the Wider Learning Ecosystem means leveraging the vast network of resources and experiences, formal and informal, that exist outside of school, including higher education, the workplace, and community assets like museums and libraries, as well as school-based extracurricular activities. Tapping into these assets is the focus of the MyWays 5 Zones of the Wider Learning Ecosystem Tool.

The 5 Zones of the Wider Learning Ecosystem

As featured in a Practitioner’s Guide about community partnerships, Natasha and her colleagues at Da Vinci Schools provide high school students with numerous real-world learning experiences throughout the Wider Learning Ecosystem. Partnerships with colleges, universities, and local businesses open up opportunities for apprentice adults to participate in dual or concurrent enrollment in higher education, job-shadowing, internships, career-focused boot camps, and other industry-based experiences. Educators at both Da Vinci Schools and in Laramie County stress that these experiences need to be well designed to achieve the desired impact. According to Lindsey, “Earning college credits should not be random. Credits should lead to students’ goals for after graduation.” Similarly, workplace experiences “can’t just be a job. They have to build career awareness and help students prepare for their futures.”

Though the kinds of experiences mentioned above are most common at the secondary level, building learner skills to be successful in a real-world learning context can occur at any grade, and educators can gradually integrate real-world learning elements over time. Casey defines real-world learning this way: “In its simplest form, it’s learning that is hands on, engaging, and connected with the world beyond school walls.”

When deeply implemented, real-world learning looks more like this: “All students access multiple opportunities and teachers are actively involved. Teachers have built relationships with the community and moved beyond offering a one-off project,” Casey explains. For instance, at the “leading level” of the Schools That Can Real-World Learning Rubric, “Real-world experiences are ongoing throughout the course of the year. Real-world learning is part of the fabric of the school and everyone benefits.”

For schools and educators new to real-world learning, Casey offers several ways to get started, such as by designing learning projects and experiences that are hands on and involve learning by doing. Maker education is one example. She also recommends inquiry-based approaches like Self-Organized Learning Environments (SOLE), in which educators present learners with real-world problems and frame projects “as a big question to research and explore and build solutions to. Ideally, learning should be interdisciplinary as well because that’s the way the real world works.”

As a natural next step for engaging with the world outside of school, Casey suggests “having students present to authentic audiences outside of school or bringing experts or professionals into the school. They can be judges on work and help kids get a different kind of feedback. It’s an easy way to start those partnerships and build a mutually beneficial relationship.”

The MyWays Readiness and Preparation Tool acknowledges that many of the attributes of real-world learning are very different from the kind of teaching and learning that happens in more traditional schools. In addition to building educator capacity for designing authentic, hands-on, and student-driven learning, this tool recognizes that students themselves and members of the community will likely need assistance as they shift their mindsets and think about learning in new ways. Lindsey’s experiences bear this reality out. She recounts, for example, “When I tell a local business leader that simply coming in and talking about your business might be hard for a teacher to justify without an educational goal in mind, it can be really eye-opening. People from industry and the community may know little about education, but it’s not insurmountable.”

For that reason, the Readiness and Preparation Tool helps schools gauge the readiness of educators, learners, and external partners from the Wider Learning Ecosystem. It also provides suggestions and resources to prepare all three partners to co-create powerful and successful real-world learning experiences.

Resources

- The MyWays Real-World Learning Toolkit provides educators and their community partners with four tools to support the design of powerful and successful real-world learning experiences.

- The Schools That Can Real-World Learning Rubric (free to download with registration) serves as a guide to help K-12 schools reflect, set goals, and drive improvements around RWL.

- Part one and part two of the Practitioner’s Guide series "It Takes a Village" shares practices and resources from three school systems deeply engaged in real-world learning: Da Vinci Schools (CA), St. Vrain Valley Schools (CO), and Vista Unified School District (CA).

- “Who You Know: Building Students’ Social Capital” explores in greater depth why social capital is an essential part of young people’s preparation for life and how schools and educators can support students in acquiring it.

- MyWays Report 11: Learning Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies presents research, design principles, and case studies on key practices, like real-world learning, that support student development of agency, social capital, and competencies for success.

Photo at top, courtesy of NGLC: Students at Vista High School engage in real-world learning.