Project Invent Empowers Young Changemakers to Solve Real Problems for Real People

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

When students design and invent solutions for community partners, their sense of agency rapidly develops and they are more motivated and engaged in learning.

Imagine: It’s your first day of ninth grade. Introduction to Engineering Design (IED) is on your schedule. Maybe it will spark a new passion. Maybe you’ll make some new friends. Maybe it’ll be your hardest class of the year.

It’s 2020, so you log into your engineering class via Google Meet. Your teachers, Mr. Mendez and Mr. Carlsen, explain that you will be working on a special group project this year. They say that your engineering class is pairing up with another group of students: the cluster class. The cluster class is a cohort of diverse learners who have unique needs. Mr. Mendez tells you that you will be building a physical technology to help one of your peers in the cluster class overcome some of the challenges he or she is facing this year. You will be learning the fundamentals of design thinking, coding, prototyping, and entrepreneurship. By the end of the year, you will be an “inventor.” It sounds exciting, but a little intimidating.

*****

This was how the year started for Project Invent students at Frederick Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center in Chicago. Reflecting back on the beginning of the year, one student remembers: “I came into Intro to Engineering with no idea what I was gonna do. It was difficult. You’re coming into this new environment with no experience. And then you’re told that you’re going to create something that will help people. Immediately, you’re thinking, ‘How will I be able to help people? I don’t even know how to code yet.’” The 50+ ninth-graders in Frederick Von Steuben’s IED course are all part of Project Invent’s class of 2021. Project Invent is a national nonprofit organization that empowers high school students to leverage design thinking to create solutions to real-world problems. Since our founding in 2018, Project Invent has cultivated thousands of young inventors in high schools across the United States.

When educators like Frederick Von Steuben’s Julio Mendez intertwine Project Invent’s curriculum with their own, they empower their students to become passionate, fearless problem-solvers. Educators in our program push their students to look outside of their textbooks to explore challenges faced by their peers and community members. Throughout the school year, students collaborate to ideate, design, and prototype physical solutions to challenges they have identified in their communities. Project Invent creations of the past have included everything from a wristband to help individuals with communication disorders communicate with law enforcement to an on-field test kit to help detect early signs of concussion in football players.

When educators like Frederick Von Steuben’s Julio Mendez intertwine Project Invent’s curriculum with their own, they empower their students to become passionate, fearless problem-solvers. Educators in our program push their students to look outside of their textbooks to explore challenges faced by their peers and community members. Throughout the school year, students collaborate to ideate, design, and prototype physical solutions to challenges they have identified in their communities. Project Invent creations of the past have included everything from a wristband to help individuals with communication disorders communicate with law enforcement to an on-field test kit to help detect early signs of concussion in football players.

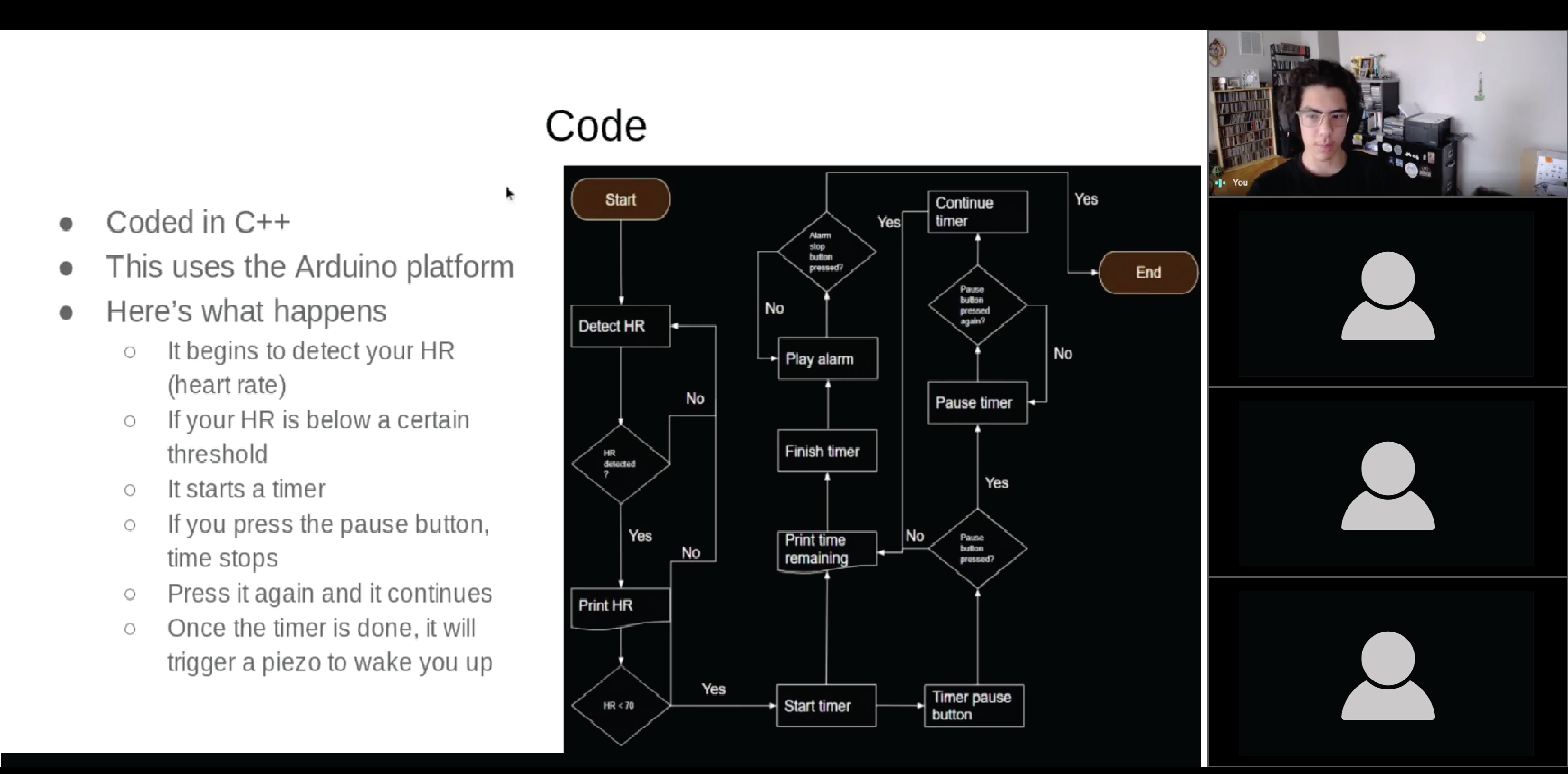

When the 2020 school year began in Chicago, Julio Mendez and his IED students kicked off the Project Invent experience by embracing the very first step of the invention process: empathy.

“We genuinely became friends.”

Divided into small groups of 4-5, student teams in each of Julio’s IED classes were matched with 1-2 of their peers with unique learning needs in the cluster class. Throughout the school year, the engineering students would call these peers their “community partners.” At first, the Google Meet sessions were awkward. The IED students were 9th graders, strangers to each other and to their community partners. The task at hand—discussing the challenges associated with diverse learning needs—was difficult to accomplish with so little familiarity among the students.

One student, Nadia, remembers: “I went in thinking that our community partners just weren’t going to talk to us. I mean, they barely knew us. And there we were on the computer screen, asking them about the obstacles they face in the classroom. How were we supposed to connect in an environment like that?”

Julio, along with student-teacher Anthony Carlsen, encouraged the students to focus on relationship-building first. They gave the students simple prompts to get to know their community partners, totally unrelated to the engineering project they were gathering for. The students talked about their favorite TV shows and go-to weekend spots in Chicago.

Anthony, a graduate student at University of Illinois at Chicago’s College of Education, watched a transition happen as the days went on: “Eventually, the students’ conversations were totally self-started. After a couple of weeks, I was able to step back, stop moderating, and really just monitor.”

Nadia sensed this change as well: “Despite the barriers of the screen, we really connected with our community partners. There came a point when we would move into a breakout room, and they’d join and say, ‘Hey Nadia, what’s up?’ I feel like we genuinely became friends.”

With a foundation of friendship established, the engineering students were able to authentically empathize with their community partners, thus initializing the design thinking process. Suddenly, their community partners were sharing personal stories about maintaining attention in class, experiencing anxiety and depression, communicating their learning differences in a virtual setting, and more.

After conducting a handful of empathy interviews, the students recognized the significance of the group project ahead of them: they were not tasked with generating hypothetical ideas. They were tasked with building real, physical solutions for real people—their new friends. As one student, Abel, put it: “It was a game changer. We got a taste of what it’s like to design something for a real person’s needs. It was so different from any other school project we had ever worked on.”

With their community partners’ needs and experiences top of mind, our Project Invent students turned to the most difficult part of the invention process: transforming their ideas into physical realities.

“I had something to prove.”

At Project Invent, we aim to cultivate mindsets that will set students up for 21st-century success. In addition to empathy, the invention process inherently develops resilience. Inventors must become comfortable with failing fast, adapting quickly, and accepting feedback as a gift. Resilience is not an easy trait to learn. But, with a community partner depending on you, resilience becomes a necessity.

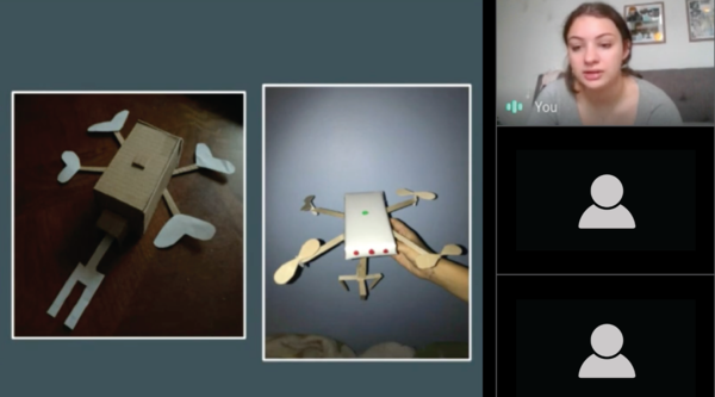

Gabriel, an engineering student developing a tool to help his community partners achieve more sustainable sleeping schedules, remembers the iterative stage of the school year as an intense one: “Our community partners knew us; they were counting on us. We had something to prove. My team felt like we had to put in the extra effort to create something that would make our partners happy. It was special because we weren’t motivated to get a good grade; we were motivated to help people.”

Gabriel and team pitch their invention, "SlpTrkr," a device that monitors students' heart rates to encourage more consistent sleep routines. (Courtesy of Project Invent)

The motivation to help real people pushed our Project Invent students to build physical prototypes, and it continued to propel them forward through one of the most challenging phases of human-centered design: soliciting feedback.

Anthony recalls a moment when his students faced a difficult truth: “It took a little bit of modeling at first. We had to provide some framing for the students: ‘Yes, it’s your project. But you need input from your community partners to be successful. Do they like what you made? Do they want you to change anything?’”

Ninth grader Abel felt tension during the early days of the feedback process. “It was so hard to create something that our community partners actually liked. We had to balance our own goals—making a usable prototype—with our partners’ individual needs and preferences.”

Now nearing the end of his Project Invent experience, however, Abel speaks fondly of his invention journey: “We ended up creating something that our classmates really liked. And we felt like we really helped them get through a tough school year. Actually, it was fun.”

“It feels really good to help somebody.”

Abel’s peer, Nadia, agrees: “Project Invent showed me that it feels really good to help somebody. When we showed our community partners our ideas and their faces lit up, that was such a nice feeling.”

While students are watching their community partners’ faces light up, Julio and Anthony are watching their students’ dreams expand and diversify. As Anthony put it, “For our students, this experience demonstrated that engineering is a human endeavor. It’s not about just making stuff to make stuff.”

For many students who would otherwise shy away from STEM-based career pathways, a human-centered engineering experience can break down barriers in mindset. “I still have no idea what I’m going to do in the future, but now I know what it’s like to see someone’s face when you have helped them. I know I want to help people,” says Nadia. Sabina, another IED student, shares a similar sentiment: “I don’t know if engineering is exactly what I want to do, but now I know that I am interested in it. That it’s an option. That I could do it if I really wanted to.”

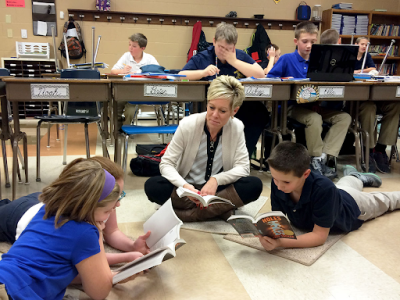

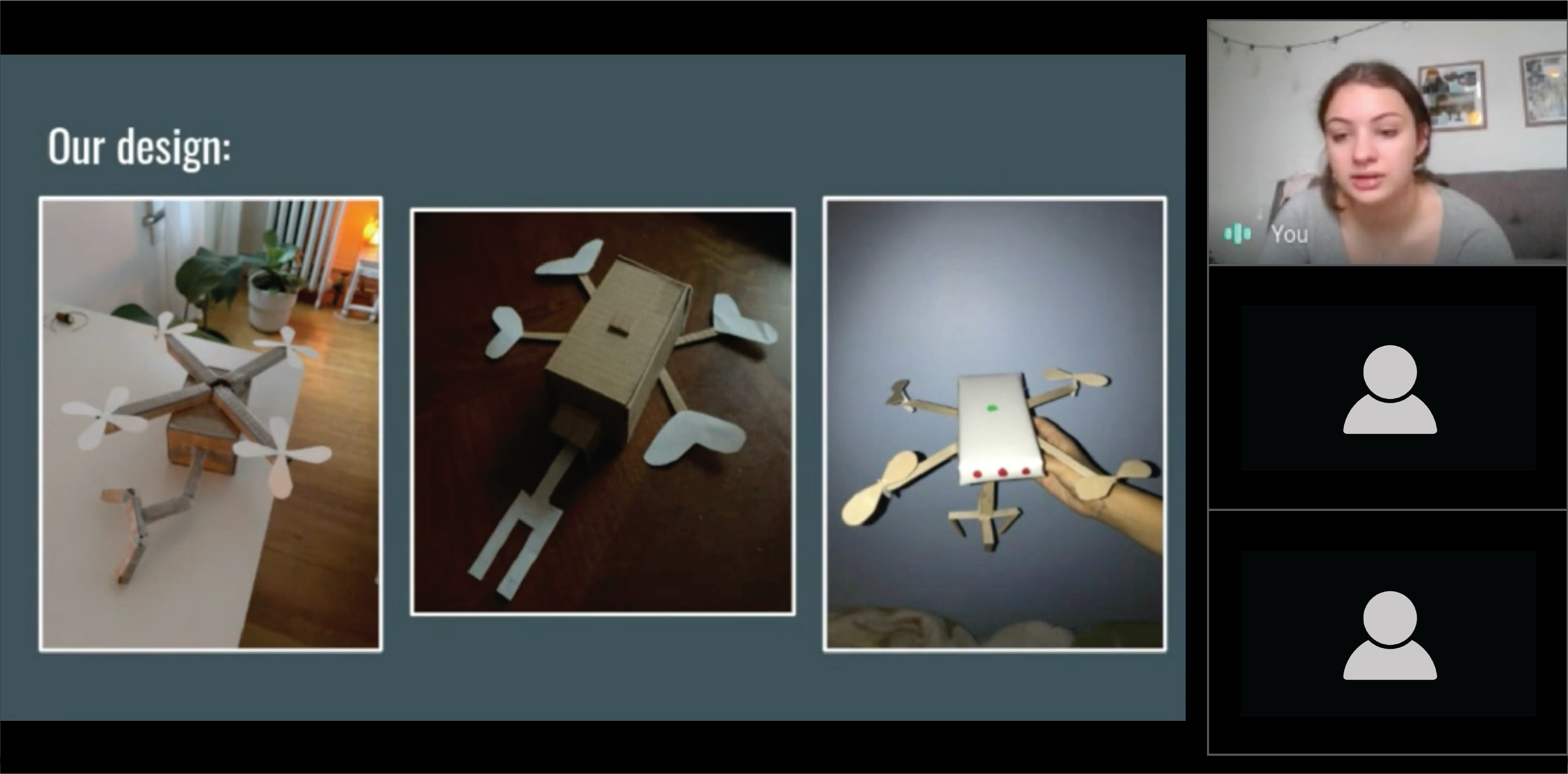

Sabina and team pitch their invention, "The Flyer," a drone that can retrieve school suppliers for students who are dialed in to virtual class sessions. (Courtesy of Project Invent)

“We never expected to get this far.”

For Project Invent students, community and classroom are one in the same. When schools give students the opportunity to solve problems that are current and relevant to the world around them—rather than problems with pre-determined solutions in the backs of textbooks—they create space for agency, creative confidence, and curiosity to naturally bloom and flourish.

At Project Invent, we often imagine: What if every student felt empowered to design the future they want to live in? What if students could impact the identification and prioritization of community challenges? What if young people tackled societal challenges head-on, rather than waiting for adults to lead the charge? If this world existed, we are certain that young people would step up to the plate.

We are certain of it because we have watched hundreds of students step up to the plate, even blowing their own expectations out of the water.

“At the beginning of the year, we expected ourselves to come up with a good idea. Maybe a good drawing,” says Abel. “We didn’t think we would ever get to the point where we would be creating a full, working prototype. But that’s where we’re at now. We never expected to get this far.”

Last year, Introduction to Engineering Design students in Chicago were told that they would become inventors by the end of the school year. It was strange. And intimidating. At Project Invent, we are on a mission to build learning environments where student inventors are the norm. Environments where “It feels really good to help people,” and “We never expected to get this far,” and “I know I can do this if I really want to,” become quotes from students in every high school.

When students exceed their own expectations, their confidence grows. When they are given real-world problems to solve, their sense of agency rapidly develops. And when we all recognize young people as changemakers, our future begins to look a lot brighter.