Racial Equity Work: Beyond Performative Change

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

Equity work is a form of deep learning and three shifts will help racial equity work in education move from performative to substantive change.

The movement for racial equity, magnified by the Black Lives Matter movement, has been the most consequential force for change in U.S. education over the past half dozen years. In a highly decentralized system where there are few central leverage points for change, it has penetrated everywhere from classrooms to school boards, from schools to universities, taking the history of racial discrimination in this country and centering the need for a forceful and long overdue response.

At its best, the movement has pushed everyone involved in education to undergo a thorough re-examination of the ways in which race and discrimination permeates many aspects of schooling and society. Equity, which in the No Child Left Behind Era was almost exclusively defined as equalizing test scores, is now a much broader concept, pushing us to think about the role of conscious and unconscious bias, interpersonal and institutional racism, and the need to create culturally affirming and anti-racist learning experiences. The more recent equity movement has been more asset-based than deficit-based, and more attentive to the ways in which good learning experiences require creating spaces where all students feel heard, seen, known, and valued.

That’s the good. But there are also problems in the ways some organizations have actualized racial equity work. We have both been in too many spaces where the performance of equity is outpacing, and sometimes distracting from, the on-the-ground work. Although the purpose of the movement is to reallocate power and material resources to create racial equity, in many organizations talk replaces action. Too much policing of each other’s words; too little shifting of power, policy, and practice. At its worst, education’s version of this movement, especially when it is far removed from K-12 students—in universities, school board meetings, district offices—can acquire a kind of precious quality, an over-reliance on jargon and conformity to saying just the right things. This, ironically, has the result of making a movement founded on inclusive action feel more like an exercise in exclusive talk.

Many of the critiques of “woke culture” have come from those who are hostile to many of its underlying ideas. We are coming from a different angle. We are highly sympathetic to the goals of the movement. But we think that if it is going to succeed in the long run, it needs to reassess the mode of work that has become dominant in some quarters. As Bettina Love recently observed: “Anti-racism work is all too often done as a performance—to be popular and look ‘woke’... it can be painstakingly ornamental.”

As we figure out how to change our own schools and organizations to become more equitable, we must practice developing empathy, identifying injustice, and taking action.

In this post we highlight three shifts that could help racial equity work move beyond the performative: from reproducing to reinventing social scripts, from shallow talk to deep learning, and from talk to action.

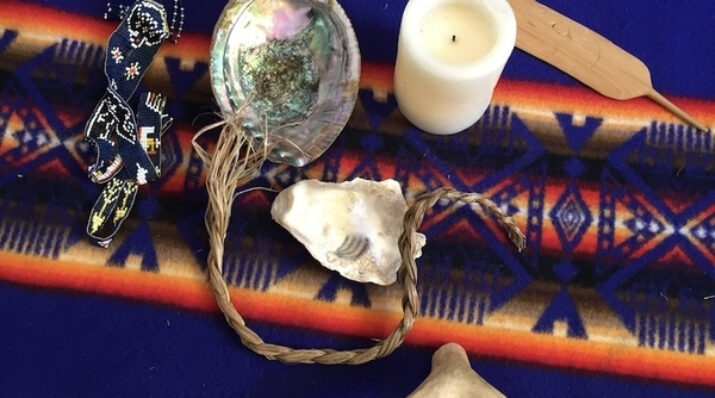

Photo by Mike Russell

From Performative Equity to Authentic Inquiry

In many places, equity work has become ritualized and bureaucratized. What began as an insurgent campaign to change norms and practices has become, in many places, a sea of acronyms (DEI) and performative scripts. Doing the work this way—book clubs around White Fragility, focus groups, revised mission statements—can be a way of avoiding change rather than embracing it.

For example, one dominant model of organizational DEI work is the diversity training workshop, which generally involves considering your relationship to privilege, developing an equity statement, and otherwise stewing in “woke soup.” The research evidence on this model of change is pretty clear—it doesn’t work. The reasons it doesn’t work are multiple: it can spark resistance and defensiveness, and it isn’t integrated with a set of constructive actions that might lead to tangible improvement (more on this below). Worse, it creates a kind of performative culture of equity, where people learn a language they are supposed to talk, but the private conversations after the workshop often diverge considerably from the public ones.

The best equity work we have been part of has been attentive to these dynamics. It is more invitational than coercive, it honors the diversity of identities that people are bringing to the table, and helps them think concretely about the nature of inequity in their community and what they can do about it. It connects people’s hearts, minds, and bodies. It is open to different viewpoints, and it helps us think about how all of us hold multiple identities, often privileged in some respects and subordinate in others. These kinds of conversations, when managed by a skilled facilitator, do not follow a script or seek to re-enact a familiar narrative, but rather are open-ended explorations of who is the room, what identities they hold, and what alliances might be formed to advance equity goals.

A big part of this is setting the right tone and building the right kind of community through shared experiences. At its worst, equity dialogues—particularly those disconnected from action—can lead to Manichean dynamics where people call out each other for every misplaced word and ostracize one another in a rush to appear more woke. This “dialogue” creates a climate of mistrust where people are walking on eggshells. A healthier approach is to acknowledge that creating change will inevitably create some conflict, and to create shared experiences that build relationships and common language authentically (see more below for an example). Healthy organizations are built on trust, vulnerability, and honest exchange, which means that we have to model those virtues in how we move toward racial equity.

The best equity work we have been part of...connects people’s hearts, minds, and bodies.

Sharing common experiences will lead to a more authentic public discussion about how to advance racial equity. In an authentic discussion, we can’t expect people to think exactly the same things. We all have different identities and experiences. There is so much complexity lurking just below the surface. For instance, consider people who believe in racial equity but have a market-oriented view of how to achieve it; people whose family members are cops and have more complex views about policing than is often welcome in anti-racism discussions; Asian-Americans, who don’t fit neatly into the “people of color” or White people divide; Black immigrants, whose views of racial progress often differ from those of native born African-Americans; and many other aspects of our identities including class, gender identity, religious views, and more. How might each person tell their own story and find their place in the movement toward greater equity in United States schools and institutions? And importantly, how can we bring our complex private identities into the public sphere of the classroom and school board meetings? Authentic dialogue and shared experiences will help people connect their individual identities to a commitment to racial equity.

From Shallow Talk to Deep Learning

Equity work is ultimately about making outcomes more equal. As we figure out how to change our own schools and organizations to become more equitable, we must practice developing empathy, identifying injustice, and taking action. Developing empathy is critical in moving from the personal to the political, identifying injustice is key in helping to see problems in terms of larger structural dynamics that produce inequities, and taking action is needed in order to make change happen. We all have our unique part to play and we must be willing to both learn as well as teach these skills.

To help foster these dispositions, equity learning has to involve deep rather than shallow learning. From a pedagogical perspective, these goals move across the head, hands, and heart; they connect the cognitive and the affective; they are about knowing, doing, and being. Workshops that enact familiar scripts through dialogue are not going to cut it. Instead, workshops should focus on creating shared experiences that involve our bodies as well as our minds. Authentic shared language will come out of these shared experiences. Together, shared language and experiences will help people unpack and interrupt inequities in their own communities.

The most powerful equity experience I (Jal) have been part of took place in Cowichan, British Columbia. The topic was the relationship between Indigenous people and their colonizers in Canada. The organizers, who were local Indigenous elders, put us into a triangular formation—one man at the front, followed by three men in chairs behind him, and then five, and so forth, all facing forward. Women were put at the back, and “old ladies” (anyone over 40!) and children were relegated to the next room. They asked us how we felt in these various different roles. Not only did the women and children feel excluded, the man at the front of the formation said that he felt very tense—he couldn’t see the people who he was supposed to be leading, and he was worried they were ready to stab him in the back. They told us that this formation represented Western capitalism.

Photo by Mike Russell

Then they reshuffled us. They put us in concentric circles—children in the center, respected elders in chairs in the circle around the children, and middle-aged adults in the outside circle, with some assigned to gather food, others to build community, and others to protect us from any external threats. They asked us how this made us feel. The “old ladies” said that they felt valued and honored. The children said they felt protected and centered. The adults said they felt like they were in community; in a circle. They told us that this formation represented Indigenous society.

Then they wiped out half of our circle—killed off half of our men, women, and children. We re-formed a smaller set of concentric circles, trying to maintain our structure but significantly shaken by the genocide we had experienced. Next they stole the children and sent them off to residential schools. They then threw down a bottle in the middle of the circle and told us that we were drunks and blamed us for our own failings. Then they killed a few more of us. And then they came and told us that they were part of a truth and reconciliation commission and asked us if we could forgive them as now they had been enlightened and wanted to be friends!

The workshop concluded with some testimonials from some elderly members of the local Indigenous community, many of whom had attended residential schools, all of whom had been asked to give up their culture in such schools, and some of whom had been physically and sexually abused. This anchored much of the previous experience, made it real, less like a workshop cooked up for our benefit and more a reporting of the experiences of actual people.

I’m still thinking about this workshop several years later. Cognitively, it helped me learn something new about the history of Indigenous-colonizer relationships in Canada. Analytically, it forced me to think about the structure of capitalism and the pros and cons of the Western mode of social organization. But its greatest effects were in the gut—I remember clearly standing in the triangle and then the circle, the shock of having our members killed, and the compelling testimonials of the Indigenous elders. It extended my empathy muscles, helping me understand, if only for a day, what it was like to be a First Nations person in Canada.

The foundation of advancing organization equity is embodied knowledge—knowledge that we own and feel in our bodies—and to achieve that, we need less shallow talk and more deep hands-on learning experiences.

From Woke Soup to Integrated Change

A third transition that can deepen equity work is moving away from equity as an isolated subject of talk, such as in organizational statements and DEI trainings, and moving toward equity as the driving force for integrated change. Less woke soup, more action-oriented change.

A research base supports this approach. The same research that suggests the failure of the diversity training model suggests that organizations have had much more success with a mode that integrates learning about equity with actually seeking to make organizational changes to support progress. They apply three basic principles: engage participants in solving the problem, expose them to people from different groups, and encourage social accountability for change. In education, we can do our own version of this.

For people who are serious about equity work, we’d suggest that they try to get increasingly concrete and specific about what they are going to try, and what it would mean to succeed.

Let’s take math as an example. As a colleague pointed out a few years ago, why is there professional development in math, and professional development in equity, but no professional development in equity in math? That’s not quite true—there is work, like that of Jo Boaler and others, that integrates the two, but where she is right is that much of the professional learning around equity has been divorced from other work going on in schools. Until we connect the two, we can’t expect much in terms of change that students experience.

Doing so will require equity work to become more specific and more integrated with other substantive elements of schooling. Unpacking the White privilege knapsack may have been good enough in 2016, but it’s not going to get us where we need to go in 2021. Even understanding that we want “culturally responsive pedagogy” or to “tap into students’ funds of knowledge” is pretty thin gruel for teachers actually faced with helping struggling readers or disengaged adolescents. Until we make these conversations much more specific, it is going to be hard to make them practically useful.

For people who are serious about equity work, we’d suggest that they try to get increasingly concrete and specific about what they are going to try, and what it would mean to succeed. Is the goal to offer culturally relevant experiences to all students? If so, what does cultural relevance look and sound like for the specific students that you serve? How will teachers elicit student and community input on curriculum, instruction, and assessments? Have teachers been involved in developing such a plan? When will they have the time and space to recast their lessons and assessments? Will teachers, students, and community members be compensated for their work to ensure that instruction, curriculum, and assessments are culturally aligned? If so, how? Similar questions could be asked if the goal is to lessen or eliminate tracking, to make the distribution of resources across schools equitable, or any number of projects that seek to advance racial equity.

This is the harder but ultimately more rewarding and sustainable way of doing equity work. The safe way of doing equity—self-reinforcing talk and no action—is initially attractive to many precisely because of its safety. It doesn’t actually change anything and is consistent with the way in which large organizations use banal talk as a way of avoiding harder choices. Actually making these hard choices is seemingly riskier—it can and will provoke pushback and opposition from those who perceive that they are losing something in the bargain. But in the longer run, performative talk will just breed cynicism and anger among those who are most committed to change—the allies in the movement will stop coming to the meetings because they will see that you are not really serious, and marginalized people will continue to experience marginalization. Conversely, there is an energy and momentum that can come with action—once people see that they can actually make progress on an issue, they are more likely to join the next campaign.

Conclusion: Equity Work as Deep Learning

Equity work is a form of deep learning. It requires developing new dispositions and ways of working and thinking, imagining, and organizing. It is a journey which has no end, but each layer builds upon the previous in ways that could not have been foreseen from the start. Effective ways of pursuing it can’t be scripted, ritualized, or bureaucratized. It needs to connect people’s identities with their commitments and their commitments with their actions. To make progress in the long run, we need to shift from the performative talk to authentic inquiry, integrate reflection with action, and develop pedagogy that reflects deep rather than shallow learning. This will allow us to reallocate power and resources in order to make real progress toward racial equity.

Photo at top by John Watkins.