The Emergence of Public and Community Learning Pods

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

Reaching for Well-Being & Learning Support for All, Part 2

Schools, local government, and community organizations are bringing small-group in-person supervision and support to more families with public community-based learning pods.

I recently wrote about the equity implications of private learning pods—small “co-quarantined” groups of students supervised in one of their own homes by a parent or hired educator while they undertake remote learning from their districts. While many of these parents are in middle class and affluent areas, of course not all parents and families creating private pods are wealthy or White. See, for example, the BIPOC-Led Pandemic Pods and Microschools Facebook group. And some families in low income and communities of color are adapting their rich local networks of mutual care to cover these new needs. But at a larger scale, many families don’t have the financial assets to hire educators to provide supervision and support learning in pods. Few working class families or even those middle class families with both parents working are able to leave their jobs or cut hours to participate in a parent-led cooperative pod. In addition, many families just don’t have access to a suitable place for a group of children to meet safely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the same time, the need for face-to-face, small group support for remote learning, for safe child care, and for students’ socialization is even greater among precisely these groups. As EdWeek recently reported, urban and high poverty schools are much more likely to employ remote or hybrid instruction this fall than rural, suburban, and low poverty schools. Forty-one percent of the highest poverty districts will be totally remote this fall, compared with 25 percent of the lowest poverty districts. The scale of the problem is daunting. As John Watkins points out, “We are facing a dramatic change in how education is structured, and it won’t benefit those students most in need unless school districts get ahead of this dangerous curve.”

Public, Nonprofit, and Community-based Pods and Hubs

Even with short on-ramps and funding challenges, schools, local government agencies, and community organizations are attempting to bring small-group in-person supervision and support to more families. Approaches vary, with new efforts coming to light each week as local communities work to use their particular assets to support their children and parents. The range of quality and care, in terms of everything from COVID safety to learning benefits, is likely to be highly variable. The offerings cluster into three types of pods (also sometimes called hubs or centers).

1. Free District Pods for Highest Need Students and Families

As districts planned for online learning, they recognized that some students and families had a greater need for face-to-face interaction and support than others. Rather than offering partial in-school time to all students, some schools are instituting totally remote models for the majority of students and using parts of their school buildings and relevant staff to provide small-group face-to-face learning to those most at risk. As one observer commented, “This isn't school, exactly. It's a ‘learning hub’...”

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Charter School in New Orleans, for example, can hold more than 600 students, but as the school year started they welcomed fewer than two dozen of their most vulnerable students in small groups. Schools in Stanislaus County, California, BRICK Education Network in New Jersey, and Adams 12 Five Star Schools in Colorado are all serving small groups of high risk students, including in Stanislaus those in severe need, “such as, say, a third grader who is alone at home daily and can’t even get on the internet, or children whose families live in vehicles or motel rooms.”

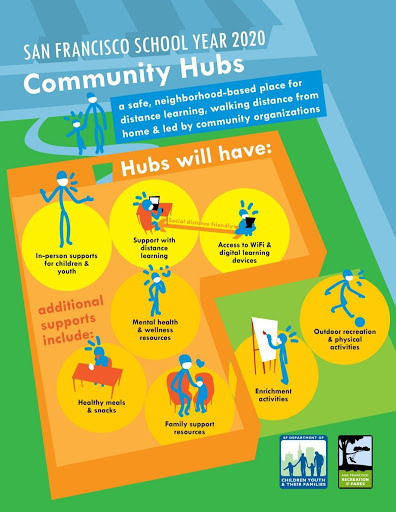

San Francisco’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families has helped San Francisco Unified go a step further by coordinating the parks department and libraries, as well as existing youth development nonprofits, to provide 40 small “walking distance” learning hub sites across the city (with plans to extend to 80 sites). This Community Hubs Initiative supports K-6 students doing the district’s Distance Learning Curriculum, with a first wave prioritizing residents of homeless shelters, public housing, ELLs, children in foster care, and low-income families “with a focus on historically impacted communities” including African American, LatinX, Pacific Islander, and/or Asian families. This priority list is similar to lists of other districts providing free hubs.

2. Community-based Learning Pods at Low to Moderate Cost

District solutions are not enough to meet the need: schools and districts have limited space to host socially distanced small hubs. They have limited staff available to supervise pods as they are busy teaching students remotely. The district programs for students “most at risk” are strikingly small. Fortunately, many other public and nonprofit organizations are joining to offer in-person learning hubs at low to moderate cost. These programs are designed to serve the many families who don’t have access to district programs or private pods.

An excellent example is Wake County (NC) Public School System, where the WakeEd Partnership launched the Families and Schools Together Initiative (FAST), a collaborative effort to support children who are schooling online. Community partners in FAST include the local parks department, children’s museum, Boys & Girls Club, and YMCA. While the goal is to provide support for district instruction, not a separate curriculum, the Y is adding a Scholarship Support Specialist who has education credentials and Support Center Counselors, primarily high school students who are vetted by the district and are fulfilling their community service requirements. The program costs $28 a day, with scholarships, free or reduced school lunch, and physical activity and STEM, art, and leadership activities available.

The list of youth development organizations putting together small, self-contained learning pod programs continues to grow. After-school, enrichment, summer camp, and other related programs can be well-suited to support students and families in this time because they have staff trained in youth development, family support, and trauma-informed care. Some also trialled pandemic podding this summer, working out health and social distance conventions (see this guide.) A few of these providers are offering an enhanced educational curriculum, such as the YMCA of Greater Nashua New Hampshire, which is partnering with BellXcell to provide evidence-supported project-based learning incorporating math, literature, and writing skills.

3. Daycare Provider Pods for School-Age Children

At the other end of the spectrum, childcare providers are also pivoting to offer remote learning supervision, with a number of states (e.g., Ohio and Massachusetts) expanding daycare licenses to enable them to take on this role. These programs can offer families much-needed solutions for safety, child care, and socialization, but it is difficult to know how supportive they will be for learning.

Public Pod Issues and Questions

We don’t yet know the trajectory of the epidemic, nor the capacity of rigid systems or overloaded individuals to react with agility and understanding. We do know that many aspects of the U.S. education system were already under stress, requiring substantial change to prepare all children for life in our fast-changing world—including addressing systemic inequities. The sudden need for students to learn outside of the traditional classroom environment has resulted in one of the most difficult “return to school” seasons ever, and learning pods may well raise more difficulties than solutions.

It’s very early in a very uncertain time. But perhaps especially at this nascent stage of this movement, it’s important to identify some critical issues to grapple with during the coming year:

- Logistical, quality, and safety issues. COVID safety is first, but lots of other logistical/quality issues are raised when learners are distributed across lots of different adults and venues.

- Equity in learning and development opportunities. The creation of private pods by some families may enable schools to focus on pod learning for those at the highest risk, and public or charitable dollars to subsidize moderate cost hubs. But we need to look closely at what gets offered in each type of pod. Will creating “separate but [not] equal” models widen the opportunity gap?

- The nature of learning and student development taking place in any pod. To some extent this will depend on what kind of district “remote learning” experiences pods are being asked to support. Are learners being asked to complete online worksheets, or are they involved in quality project-based learning (PBL) requiring student self-direction and authentic products? If the former, will pod leaders be able to add deeper learning experiences? If the latter, which pods are able to support students engaged in more active learning?

Some private pods will excel in this (pod leader recruitment ads have included requests for Montessori or PBL experience); some community organizations have deep expertise in empowering youth development experiences; and individual parents, educators, and students themselves are expressing eagerness to use pod learning to address broader, 21st-century skills that some schools have under-addressed. Pod leaders in any of the settings may see themselves in a more minimal “monitoring” role. Or on the other hand, they may enrich pod time with learning related to racial or ethnic identity, nature, religious topics, or civic action—whatever the interests of the students or community. What are the opportunities and risks, how will districts even be aware of what additional learning is happening, and how important is that? - The critical need for additional funding. Extending small group learning to all will require deep investment. Private charitable funding will play a part but equitable provision will require additional federal funding for education and childcare. The emergency federal funding for education in the first COVID-relief bill was five times less than what our education system received in the Great Recession, and we don’t know what else will be approved. Meanwhile state and local education funding is dropping.

At the same time, whenever a vaccine enables students and educators to get back into their classrooms full time, it will also be worth asking ourselves how to build on the learning pod experiences of this year:

- Can we summon the energy and will to “build forward” by iterating the positive elements of the small pod experience to re-think our students’ learning experiences? Can we double down on addressing and eliminating elements of the experience that, despite best efforts, exposed and/or further promoted systemic inequities?

- Can we build on the hurriedly established or expanded partnerships with parents and community organizations to develop more real-world learning experiences that are aligned with student interests, identities, and local opportunities? That is, maybe we shouldn’t “go back to classrooms full time,” comforting as that sounds to some, but instead embrace a wider learning ecosystem.

- Can we continue to transform the role of teachers in some of the ways that have been introduced, albeit sub-optimally, this year—as learning guides for students to direct their own learning by accessing experiences online and from the world around them to reach their goals?

- Can we organize the practice and policy ecosystem to effect the significant systemic changes necessary to promote and improve equity for whole child development? Can we reach into the health, mental health, child care, housing, and employment infrastructure that remote learning and the creation of learning pods has helped reveal as part and parcel of learner experiences?

Image at top by congerdesign.