We're All In: When a Team of Students, Educators, Parents, Elected Officials and Community Partners Visit a High School Together

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

When a team from Franklin, New Hampshire visited Mission Vista High School in California, they had two big questions: What could we learn from them about how to do high school differently, and what could we learn about ourselves?

New Hampshire is a unique state. First, we love to be first, if we can. We were the first state to declare independence from England in 1775. The first American to space was from New Hampshire along with, sadly, the first private citizen to be sent to space, Christa McAuliffe. We love to have the first primary in presidential election season; we'll see how that turns out next year. And, since this is a post about education, New Hampshire was the first state to adopt competency-based assessment policy for its high schools, although to be honest, we didn’t go as far as the folks who came after us.

Our second distinctive feature? Our government structures. Town governments allow for direct democracy at least once a year, where your vote literally counts. Check out this story about Croydon, New Hampshire, to learn more about that. And, we have the smallest representative-to-population ratio in the country; every 3,300 or so people get a representative in our lower House of 400. That's incredible when you think about California, which has only 80 representatives in theirs for nearly 40 million people.

So, taking a team from Franklin, New Hampshire, on a site visit to Mission Vista High School in California as part of an NGLC Learning Excursion was going to be a bit of a culture shock. Despite the differences in population density, demographics, education policy, and weather, we went in with two big questions: What could we learn from them about how to do high school differently, and what could we learn about ourselves?

If we just rely on the school community to make the change, it won’t be sustainable. Community input is important.

Learning #1: If we really want change at Franklin High School, we need all kinds of folks to be ALL IN.

When the invitation to apply went out, I was intrigued by the call to bring a team of different perspectives in the community. Our team of 12 was made up of students, administrators, parents, elected officials, and community partners. Many had not experienced an educational conference or school site visit before so pre-work was important. We needed to build a common vocabulary and make sure edu-speak wasn’t a barrier.

In our debrief sessions, both in California and at home, we struggled with some big questions. How do we get everyone to buy-in if we can’t get them to participate now? How do we make this change, leader-proof? How do we get other folks excited about the possibilities the team saw for project-based learning at Mission Vista?

The answer, ultimately, is that we need all kinds of folks in Franklin to be part of the conversation and excited to be part of the conversation. Of course students and teachers are central, but also we need the support of parents and community partners. The school can’t do this alone. With only 8,500 residents in our community, and about 15 percent of those already connected to schools, it should be easy, right?

If we just rely on the school community to make the change, it won’t be sustainable. Community input is important.

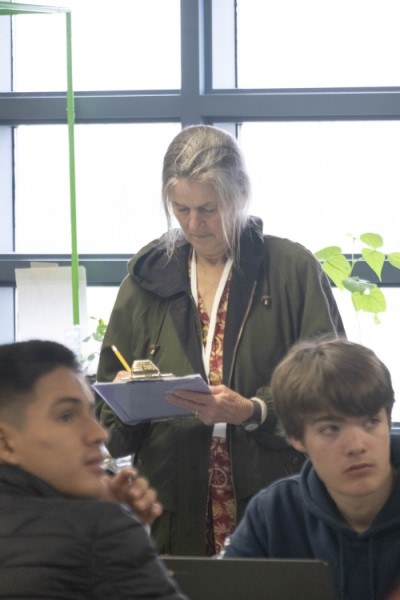

A community partner on the Franklin team taking notes during a classroom visit at Mission Vista High School. Credit: Mission Vista High School Photography 2 Student

Learning #2: Let’s use New Hampshire policies to our advantage

I firmly believe New Hampshire has the most liberating education policy in the country, despite recent ambiguous laws that make providing an honest education a little trickier. Essentially, the legislature tells us what to do, but not necessarily how to do it. Schools have to teach broad subjects, but schools can adopt their own standards. Schools K-12 should be competency based, but schools can choose what those competencies are and how to organize time. Twenty (20) credits have to be earned to graduate high school, but no one has defined what evidence students have to produce to earn the credit. Certain types of policies are required, but those policies can differ from district to district. Sometimes it feels like the Wild Wild West out here.

In general, however, schools, including Franklin, are operating very similarly to the way they did 50 or even 100 years ago. Students focus on earning grades and not necessarily on learning. Tightly timed bells move kids from space to space, regardless of the subject, and speaking of subjects, they are still compartmentalized. Math is math, science is science, and history is history.

While our team was at Mission Vista High School, we didn’t actually see structures that were radically different from what we’ve had in New Hampshire for the past 20 years, including a four-by-four block schedule. Franklin moved beyond the block because it just didn’t work for this community. But, what we did see was what a school could look like when kids were engaged because they were doing projects and studying topics that they were personally interested in and connected to.

So, how does Franklin, or any school in New Hampshire, get to a model like Mission Vista, a dual magnet school where choices abound? The answer: We have to be resourceful and use New Hampshire policy, not past practice, to our advantage.

One idea that came from our team was rebranding the core. Take English as an example. Every 9th grader takes English 1, worth one credit. Why couldn’t that course be offered as four ¼-credit courses where students could choose the topics of their choice? Too often we reserve these electives until junior year. Why are we still doing that? Same with biology. What if we offered Biology Basics for ¼ credit, then open it up to whatever biology topics students are interested in?

The team had so many ideas on how to do school differently, and the barriers were not state policy but our own self-imposed limitations, which the superintendent reminds his team of often.

A Mission Vista High School student takes a small group through the school campus to visit classrooms. Credit: Mission Vista High School Photography 2 Student

Learning #3: Get the kids outside and take breaks often

Mission Vista has a beautiful campus with what I’m going to call exterior corridors and a lot of outdoor seating. When kids move from class to class, they have to go outside. Even though it rained both days we visited the school, many on our team marveled how nice it must be for the kids to get outside between classes, what we call passing time. They even brainstormed ways to make it happen at Franklin.

The point is, taking a walk and getting some fresh air is good for the soul and the brain. We should make sure our students do this more often, even in high school. A lot of the work kids are doing in high school requires some deep thinking and brain power. We should honor that and get kids out even if we don’t always have Southern California weather.

Walking outdoors to classrooms on an unusual rainy day in Southern California. Credit: Mission Vista High School Photography 2 Student

In the same vein, our team wanted to think about how much time kids have between classes. The lovely thing about most educational conferences is that they are not go, go, go. Usually there is at least 15 minutes between sessions so that presenters can recharge and participants can take care of their needs and debrief. We should afford young folks and their teachers with this time as well.

This year, Franklin moved from three-minute passing to five. It’s had a lot of positive feedback from students, who get to breathe a bit, and staff, who have a minute to set up for the next class, talk to a student between classes, or, you know, use the bathroom.

The Franklin team learned more than this, that’s for sure, but these three takeaways are getting us started. The district is beginning the next phase of strategic planning and has an inclusive plan to connect with community members about their hopes and dreams. A new schedule promises to open up some possibilities of classes like The Physics of Skateboarding, Snowshoeing with Robert Frost, and a surprising favorite, the History of Franklin. And, we’re thinking a lot about breaks and how to build them into our day so that everyone has the time they need to be successful.

Photo at top of the Franklin team, courtesy of NGLC.