Why Transforming Public Education Is So Damn Hard

Topics

Today’s learners face a rapidly changing world that demands far different skills than were needed in the past. We also know much more about how student learning actually happens and what supports high-quality learning experiences. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Our public schools mirror all the ways our society works. Changing them—really changing them—means challenging some long-accepted norms, and replacing them with… what, exactly?

“How we spend our days is of course how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour and that one is what we are doing.”

–Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

For Annie Dillard, our daily choices are fractals for our entire lives. How we choose to be in this hour or that one looks pretty much like how we choose to be over a lifetime.

I think she’s on to something, and I think her observation is incomplete. For Annie Dillard and for all of us, our daily choices add up to—and at the same time, profoundly reflect—much larger fractals than simply our own individual lives. How we are and what we do every day, over many centuries and through the infinitely complex, often cruel, sometimes miraculous dynamics of human society-building, is also how we have designed our society to be.

Our society’s design—by design—doesn’t distribute the ability to make daily choices equally. Annie Dillard is among the fortunate. But over recorded history, the societies humans have designed have severely restricted the available daily choices for most of humanity. How human societies say the people in them should spend their days and lives has an awful lot to do with how each of us—some more than others—end up spending them.

Our schools are fractals of the larger forces in our society’s design—forces that relentlessly shape how they work and how adults and kids alike behave in them.

Our public schools perfectly reflect all of this, not only in what they’re like today but in how they got that way. Our schools are fractals of the larger forces in our society’s design—forces that relentlessly shape how they work and how adults and kids alike behave in them. At the same time, every one of this country’s four million educators makes dozens of choices every day that shape how the students experience their education and the design of the society they will inherit as its caretakers and (perhaps) its redesigners.

Let’s play this out, looking back to the roots of our public education system:

- Adults in previous generations designed our schools to serve perceived societal needs in those times for disciplined workers for an industrializing economy.

- Students experiencing those schools grow up to become educators and policymakers and parents whose concept of “school” has been deeply shaped by their experience of it.

- These adults make choices every day that either fulfill and prolong that foundational design or challenge and reimagine it. Mostly the former, I observe, and that is entirely by design as well, since industrial and organizational thinking of the early 20th century prioritized rule-following over empowerment and carrots-and-sticks over intrinsic purpose and personal agency.

That’s what we’ve all inherited in our public education system: a completely self-reinforcing, relentlessly self-repeating closed system. No wonder so many teachers live for shutting their doors and closing out the noise. Most of that noise, they accurately sense, aims to narrow their field of choice in how they work with their students.

This helps explain something that’s important for everyone involved in the transformation of U.S. K-12 public education to understand: why this work is so damn hard.

Perhaps you have heard the parable that writer David Foster Wallace told at the beginning of his 2005 speech to the graduating class at Kenyon College:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

Next gen learning educators (and policymakers, and parent and community advocates, and funders) seeking to transform learning and deepen student outcomes find that work so challenging because they are literally trying to help everyone around them see the water they are swimming in—many of them for the very first time. That water is the whole set of systems, mindsets, structures, and processes that, put together, create the reality of what teachers, administrators, and especially students experience in public schools every day. These systems and mindsets are so deeply embedded and so thoroughly consistent that they are essentially invisible, like water to a fish.

And yet: those systems, mindsets, structures, and processes are not in fact part of the natural world. They were invented to manage human nature and designed to serve the interests of society—as interpreted and directed by people in positions of power (namely, White people, mostly male, here in the West) with deep self-interest in retaining and expanding that power, whether its roots lie in money, politics, or religion. This is true not simply of public education, but virtually all sectors of life, business, politics, and culture. It’s the mega-fractal, the paradigm of organizing Western human civilization that emerged in the Middle Ages, took root during the early Renaissance, was furthered in the Enlightenment, and became embedded societally, economically, and industrially in the hierarchical and bureaucratic systems of the late 19th and early 20th centuries—including in race science and eugenics. This paradigm has strongly influenced the structure and processes of American public education as well as our society’s beliefs about intelligence and academic merit. Now it’s the water we all swim in. We are so immersed in it that we don’t see it as one belief system among other possibilities.

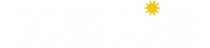

Here’s how what we might call the Western Industrial paradigm has played out in U.S. public schools. Core characteristics of that paradigm are listed at the top of the graphic, and the ways they affect our society’s operating codes—within our context, in public schools—are shown in the arrows that follow.

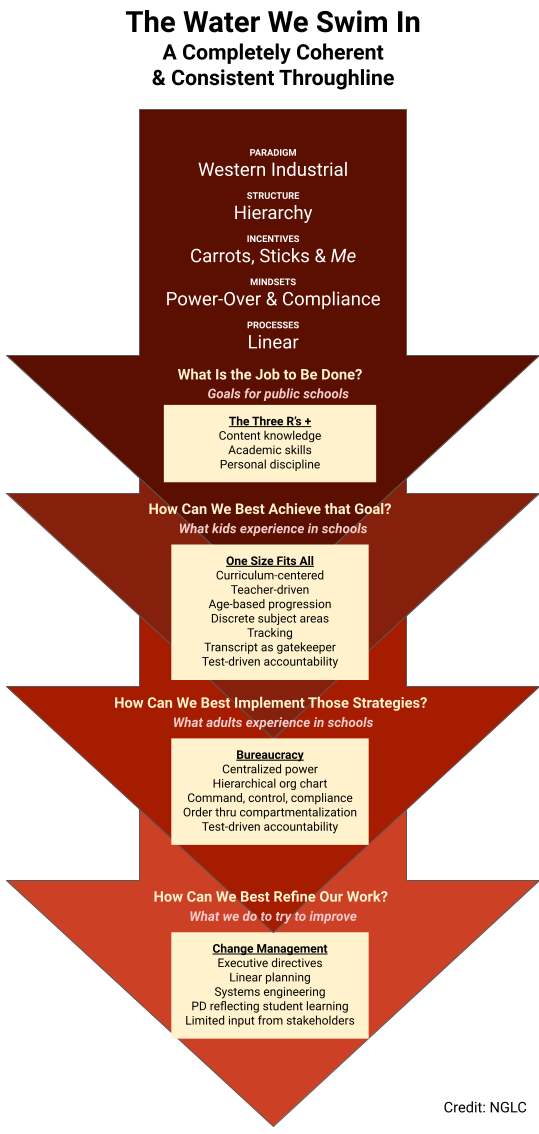

That Western Industrial paradigm likely looks very familiar to most educators. We readily recognize its component parts, even if we don’t think about them as reflecting the tremendously consistent throughline—from societal incentives and mindsets to public school structures and processes—that it is. Now let’s consider a different paradigm, one that is influenced by the natural world and also by some Indigenous cultures, shown in the graphic below.

I’m calling this “Indigenous Natural” because it reflects attributes drawn from many Indigenous cultures around the world and the supremely adaptive, highly networked, and profoundly interdependent characteristics of nature. (For a compelling examination of Indigenous organizational thinking, read Ulcca Joshi Hansen’s fine book, The Future of Smart. For a wonderful exploration of the adaptive, interdependent characteristics of nature, read The Secret Wisdom of Nature by Peter Wohlleben.)

The Western Industrial paradigm may have many elements in it worth building on, but make no mistake: it has also either generated or provided a fertile environment for our society’s most pernicious, soul- and community-crushing evils.

Where does all of this leave us? It would be easy—all too easy—at this point to rush headlong into the “either/or” polarity thinking that runs through virtually every dimension of human life in the 21st century. After all, there is a right and wrong answer here, isn’t there? Regarding which of these paradigms is better and the one we should all commit to?

Well, actually: I don’t think it’s quite that simple.

When NGLC set out in 2018 to identify and study school districts that had successfully pursued fundamental redesign of student learning for a decade or longer, we became fascinated by six communities that had gone about this sustained transformation effort with deliberate difference from what we were seeing elsewhere. They weren’t using identical language, and the arc and sequence and path of their change efforts were unique.

What they all did develop over time, though, was the same central driver for their work: the supposition that their central vision, their 21st-century, whole-child reimagining of student success, needed to shape not only their student learning model, but their adult operating culture as well, and even the very ways they were going about catalyzing change. They were (and most still are) pursuing radical coherence in their goal and the ways they went about pursuing that goal. For more on this, see the Transformation Design website, and my 2020 article When Humans, Not Systems, Run Schools that describes the way this radical coherence shaped their response to the pandemic when it hit.

Furthermore: it strikes me that this idea of complete, radical coherence extends across both of the throughline paradigms I have presented in this article. Integrating ideas from both paradigms vividly demonstrates the “power of with,” the premise of the first article in this What We Need Now series:

- Vision: Standards (not standardization) and academic expectations with whole-person development. The so-called hard and soft skills do not compete with each other; their development goes hand in hand. Academic skills develop when learners see purpose; life skills develop within contexts of content.

- Learning Model: Direct instruction with project-based learning. There’s no time and not much if any reason for educators to engage in either/or, us-versus-them reading, math, pedagogy, or assessment wars. It’s time to step off of the altars, stop worshiping one-dimensional shrines, and strive to blend the best of both sides across all of these false-dichotomy arguments.

- Operating Model: Clear organizational structures to get stuff done with reverse engineering to distribute agency and power. We have all likely experienced both extremes: centralized power that deflates everyone else’s will and creativity, and decentralized authority that can’t accomplish anything because decisions are so hard to make. The integration of the productive aspects of both models is an art—and a necessity.

- Change Model: Linear systems engineering, continuous improvement, data analysis, and more with deep commitment to inclusive, equity-seeking emergence and to catalyzing over managing. Change can be disciplined and ideative at the same time. Carnegie Foundation’s improvement science, NGLC’s transformation design, and National Equity Project’s liberatory design all represent ideas that become more powerful and more effective when they are blended with each other than when they stand alone.

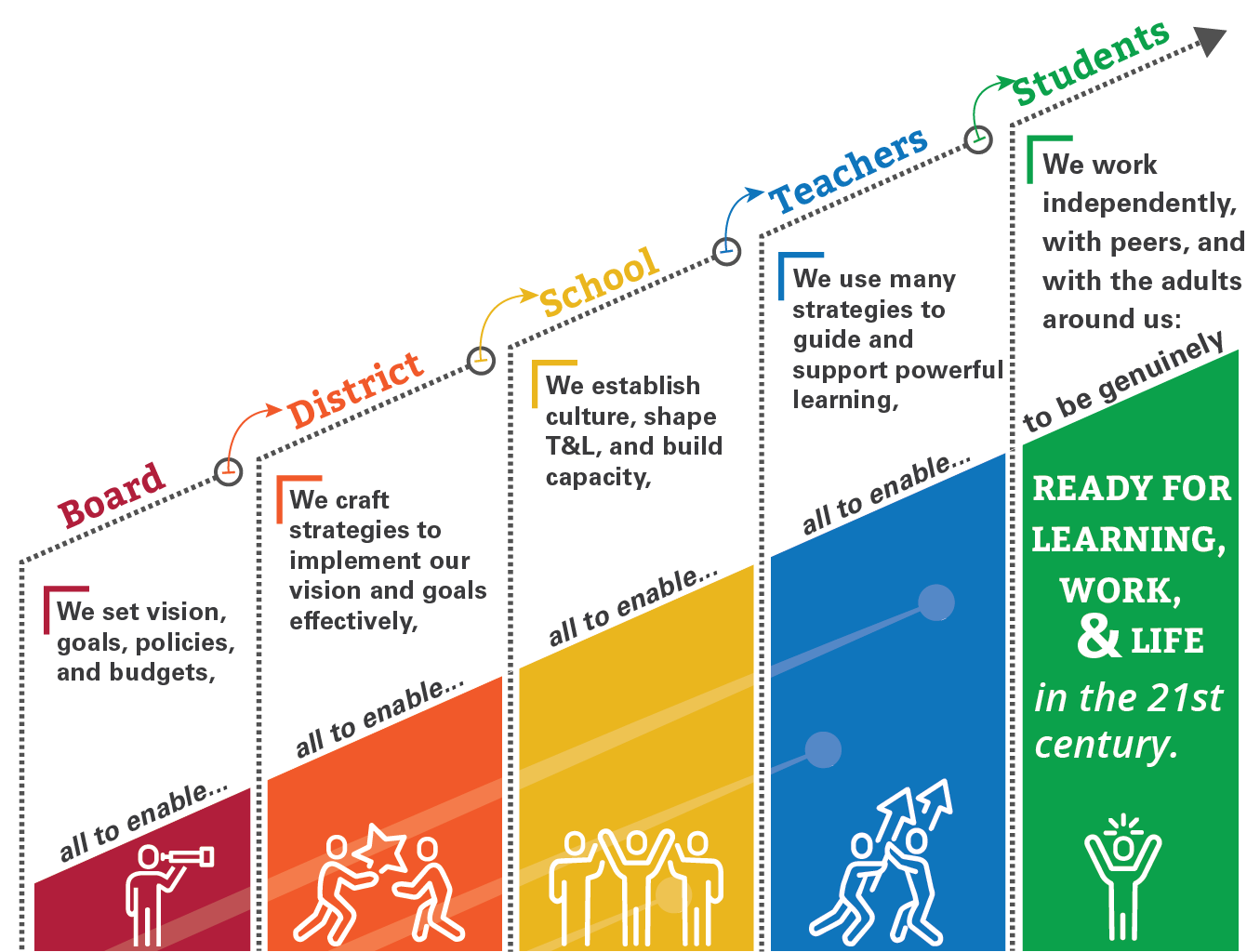

What does all of this start to look like in practice? These approaches are all reflected in the graphic below, from NGLC’s 2022 What Made Them So Prepared? project. In mature next gen learning systems, each organizational level in a school or district defines its job as empowering and enabling those at the next level to do the best work they can possibly do. The learning model the students experience with their teachers mirrors the operating model that teachers experience with their principals, and that principals experience with their superintendent.

Credit: NGLC

When teaching and learning embody the same attributes as policy-setting and district/school management—all of it shaped by the “both/with” blending described above, using the best of both organizing paradigms—that is systemic and cultural consistency at a radical level.

Impossible? Why should it be? Again, we know exactly what this kind of consistency looks like and feels like; we could all sketch the parallel graphic that depicts current, pervasive organizing hierarchies and norms. Most kids in most schools today experience exactly the same top-down, power-over dynamics that their teachers would say they generally experience, and that their principals would likely say they experience.

If there’s anything public education knows how to do, it’s consistency. It’s just that we’ve remained stubbornly consistent around a set of societal norms that include a number of outmoded precepts. Some of those precepts are simply counter productive; others, though, carry and institutionalize the mindsets and systems that have long provided choice and opportunity to some classes of people and denied them to others. That Western Industrial paradigm may have produced medical marvels and diminished global hunger and may have many elements in it worth building on, but make no mistake: it has also either generated or provided a fertile environment for our society’s most pernicious, soul- and community-crushing evils: systemic racism, structural inequality, White supremacy culture, vast income disparity, colonial imperialism. These forces stand squarely in the way of peace, social justice, global welfare, and human advancement. We must all work together to end them—or they will prove to be the end of us.

What’s the best way for that to happen? Not to dismiss literally everything in that paradigm, but to extract from it the useful bits and blend them with the best bits of other worldviews. We would all do well, in fact, to take a page from educators like those in the six districts NGLC studied. They live a kind of integrated double life: conceptually in the future (that’s why they are in the education business), and experientially—relentlessly so—in the here and now. (The kids are in the schools and need to be served, today.) This combination helps them blend a spirit of continuous inquiry and innovation with a ferocious practicality.

Wouldn’t we all be better off if we leaned into the one thing all humans share—wanting a good and fulfilling life for our offspring—as the primary driving principle for organizing literally everything?

This is tremendously hard to execute, but perhaps easier to support in concept. Leveraging the power of with: wouldn’t our best progress come from blending strong aspects of both paradigms, and using that sense of the collective to reject the perniciousness of the Western Industrial paradigm and mitigate the inefficiency of Indigenous Natural? Wouldn’t our younger generations be better off for this blending, rather than serving as pawns in the unending us-versus-them battles of adults? Wouldn’t we all be better off if we leaned into the one thing all humans share—wanting a good and fulfilling life for our offspring—as the primary driving principle for organizing literally everything?

Maybe so.

But I’ll tell you why that’s so hard.

It’s because we aren’t seeing the forest for the trees. Or, in the spirit of the metaphor we’ve used in this article: we aren’t even seeing the water we’re swimming in, much less the wide blue ocean beyond.

About This Series

This is the second in a series from NGLC Co-Director Andy Calkins on What We Need Now. In the spirit of co-blogging, co-reflecting, and the power of with (see the first article for more on the power of with), feel free to define the “We” in What We Need Now in whatever way appeals to you most. Also in the series:

- The Most Important Word of the 2020s (and Maybe, the Millennium) - What would happen if we all organized around doing things with, rather than to or for our intended beneficiaries?

- If Your Reform Doesn’t Show Up in the Learning Lives of Kids… Did It Ever Really Happen at All? - It’s time to replace “trickle-down” ed reform with change efforts that start with students and learning.

Image at top by Pixabay, CC0.