From Compliance to Engagement to Agency

Topics

When educators design and create new schools, and live next gen learning themselves, they take the lead in growing next gen learning across the nation. Other educators don’t simply follow and adopt; next gen learning depends on personal and community agency—the will to own the change, fueled by the desire to learn from and with others. Networks and policy play important roles in enabling grassroots approaches to change.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Insider teacher insights on moving Design Tech High to a school with an 'extreme personalization' focus; resources included.

When I began my teaching career, back in the Dark Ages (the late 1980s, that is), the name of the game was compliance. If my principal walked into an orderly classroom and saw me talking at the front while students quietly listened, I was considered a competent teacher. This was before content standards even existed, mind you, and the emphasis was on what the teacher taught, not on what the students learned. The theory, as I understood it, was that if I broadcast high-quality content every day and students compliantly “received” it, then learning was happening.

Student-centered learning and some degree of innovation were tolerated, but not encouraged. I recall one occasion in which my lit students were working in groups on self-selected stories about the war in Vietnam. The principal popped his head into the classroom and found me perched beside a group discussing symbolism in Louise Erdrich’s “The Red Convertible.” His comment as he ducked out? “I’ll come back another day when you’re teaching.”

Quite a lot has changed since then. Even in the most traditional schools, educators know that what is learned is more important than what is taught. In my years as a classroom educator, I saw compliance give way to engagement as the North Star of instruction. I and my colleagues understood that active learning and co-construction of knowledge were essential, and we worked very hard to create engaging activities and experiences to support those goals. However, we teachers were still the ones directing the learning. If the classroom was an orchestra, I was still composer, conductor, and audience.

Today, many schools and districts in the NGLC network and beyond have taken the next steps toward true student ownership of learning. Whether educators call it agency, voice and choice, or personalization, more and more students are empowered to direct how, what, and when they learn. What it means to be an educator has also changed as a result.

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I interviewed educator Lilia Pineda about her experience moving from traditional approaches to an “extreme personalization” model at Design Tech High School, an NGLC grantee school in Redwood City, CA. When Lilia started teaching Spanish at d.tech last fall, she already had eight years of secondary teaching experience in three traditional charter schools and had worked as a district-level Spanish content director. She spoke to us about her transition, focusing on:

- What personalization looks like for her and her d.tech students

- How her role and experiences as an educator differ from those in more traditional settings

Lilia Pineda, teacher of Spanish I and III at Design Tech High School

It’s All About Choice

Design Tech High (d.tech) is guided by two principles: extreme personalization and putting knowledge into action by solving real-world problems using a design thinking approach. In this model teachers are considered learning experience designers who continually iterate their practices and the organization as a whole to best serve students’ needs.

“When I was interviewing at d.tech and talking to teachers, I wondered about ‘extreme personalization’ and especially what that would look like in world language,” Lilia recalls. After a summer of conversations with colleagues and a semester of teaching, she sums it up this way: “Extreme personalization is about knowing your students academically, culturally, cognitively, and personally, and a way that I see this as possible is by giving them choice.”

Self-paced, tech-enabled independent learning may seem an awkward fit for a subject as interactive as Spanish, but Lilia has designed her classes in a way that leverages the strengths of traditional models while also incorporating a high degree of student choice. She describes a typical week in her Spanish I class: “At the beginning of each week, students know which skills they’ll need to master by Friday, but they have choice about when, how, how many, and with whom.”

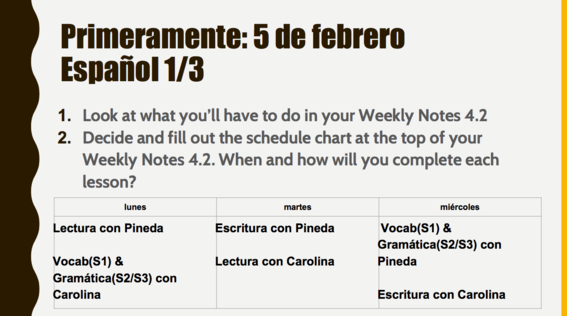

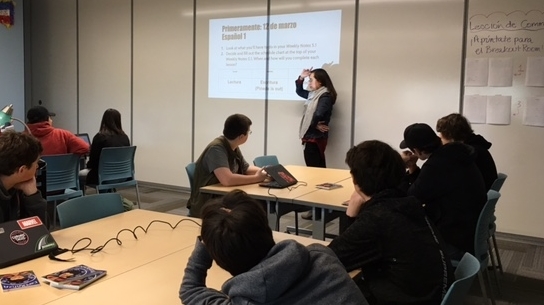

As part of their Monday “Primeramente” (a Spanish version of a “do now”), students create a personalized schedule and make decisions about whether to work independently at their own pace on the computer or to request one or more teacher-directed lessons. They can also sign up with a partner to use an adjacent room for speaking and listening practice.

Students can can choose to work independently or opt in to teacher-directed lessons offered during the week.

“It’s a bit challenging,” Lilia acknowledges. “I have to be planned a week ahead and have all of my lessons ready on Monday. It’s a lot of work at the front end, but it is helpful for students to be able to make those decisions. Students have really gravitated toward this model of extreme personalization. They are really owning what they do and when they do it.”

The Challenges of Ceding Control

“Something students like is that they just have to prove that they are mastering the material. They could do every single lesson with me and get extra personal attention or almost never work with me except to show what they’ve learned.” Lilia admits that this level of choice felt strange in the beginning. “It was a bit of a struggle. I was so used to thinking that I needed to have the whole class with me. But I told myself, ‘I need to trust them. They are going to decide for themselves what works best for them.’ It was about letting go of controlling the classroom.”

This does not mean that Lilia removes herself from students’ decision-making processes. Part of her role is to have conversations with individual learners about their progress and, based on their performance the week before, invite them to join her lessons as needed. She tells the story of how her Spanish I class came to appreciate and see for themselves the value of teacher-led lessons. “At the very beginning of the year, the 9th graders said, ‘Great! I can do this all by myself’ and opted to do only independent work, but within a week we all realized they needed my instruction. It’s definitely personalized in that the students know they have the freedom, but they can always come to me and ask for help or I can approach them.”

Another aspect of extreme personalization that Lilia found challenging concerns learner agency around performance levels and grades. Not only do d.tech students choose when and how to learn, but they also can decide how much to learn. For example, students can schedule themselves to complete the minimum number of lessons that week to earn a C, take on an additional lesson, such as a speaking or listening module, for a grade of B, or complete them all to earn an A. However, unlike in a traditional setting, this is a conscious and deliberate choice on the part of the learners.

“Some students who just need the credits might choose to do the minimum,” she explains. “As a world language teacher it was hard for me to accept, but honestly, you would see that in a traditional classroom as well. It’s a matter of making peace with that.”

As part of each Monday’s Primeramente activity, Lilia projects the lessons of the coming week onto the (movable) wall so that students can create their learning schedules.

Pleasant Surprises

Although the personalized model required some adjustments, Lilia cites many advantages of working at d.tech. One of these is her students’ high level of effort and Spanish proficiency. In her previous schools, Lilia often taught AP classes to Spanish heritage speakers. When she took a position at d.tech teaching non-native speakers—including many beginners—Lilia assumed she would have to lower her expectations, but this has not been the case.

Even though students can opt to do the minimum, she notes that “quite a lot of students push themselves and do more.” As evidence of success, she points to the quality of language use she is finding in students’ recordings of speaking lessons, Socratic seminars, essays, and other performance tasks. Their vocabulary, too, seems to be more advanced. Describing her Spanish I unit on food, she says, “I’m just giving them basic vegetables or fruits, but they want to say more, and they are filling in the gaps in the vocab list. They are pushing themselves to look things up and doing a lot of learning on their own. It’s really impressive.”

Another key benefit of working at d.tech is the freedom to innovate that is central to design thinking. Building on professional learning around brain science, Lilia and her colleagues are, as she says, “always thinking about the best ways to learn, what it would look like in our teaching, and what are some innovative ways to do it.” This semester, for example, Lilia and the Spanish II teacher have experimented with use of space, one of d.tech’s levers for personalization. They removed the wall between the two classrooms so that students could choose between the two teachers for some of the lessons, get help from more advanced Spanish speakers, or interact across grades around a book they are reading. As the next step in her professional growth, Lilia plans to test out more varied modes—and more choice—of assessments in her courses.

Lilia finds d.tech’s culture of innovation liberating. “Design thinking was new to me, but it really works. We test things out and see how the students take to it. It’s very different from my past experience in schools, where I always felt I had to follow a mold and do what was expected every single day.” Though she concedes there’s some value in such structure for brand-new teachers, Lilia says that, “As a teacher with experience, I’ve always wanted a bit more freedom, and I think that’s what Design Tech has provided me.”

As Lilia pushes herself to innovate and give students more agency over their learning, she is certain of the support she’ll receive from school leaders. “The mentality here is great. It’s OK to test something with students, modify it, try it again, or get a new idea. It’s even OK to mess up. That’s part of the learning. There’s flexibility and choice for students here, but also for teachers.”

Resources

- Design Tech’s staff-facing playbook for using design thinking to manage change in their organization

- Personalization cards identifying a few of d.tech’s more common levers to personalize instruction for students, including choice of topics, tasks, space, and teaching modes

- Sample writing and speaking performance task from Lilia’s Spanish I class

- Design Tech High’s graduation requirements, including four years of Design Lab