A Tale of Two (English Language) Learner-Centered Schools

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

Practitioner's Guide to Next Gen Learning

Two schools use next gen learning design principles to enhance the learning experience of English Language Learners and all their students.

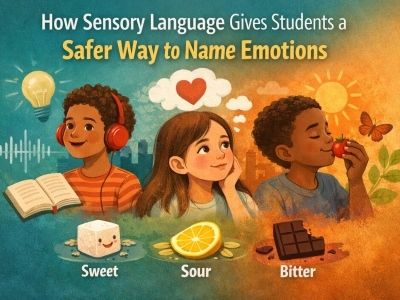

It’s mid-morning at Omar D. Blair Charter School in Denver, Colorado, and it’s time for dance class. “Stage right, dancers!” calls Bashir Sanders, a member of the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Ensemble, as well as the teacher of this energetic group of learners. School has only been in session for about a week, but the young dancers already know the drill. Karen Lord, the school’s English Language Learner coordinator, kicks off her shoes and joins in the dance—to the delight of the children.

“We’re very touchy-feely here,” Karen explains as we pass the office, where a father is putting the final touches on a tray of birthday cupcakes. “It’s a tightly knit community with a family atmosphere.” The diverse K-8 school in Denver’s Green Valley Ranch neighborhood takes its name from Dr. Omar D. Blair, a World War II Tuskegee Airman who later became the first African American director of the Denver Board of Education. English Language Learners make up 27.5 percent of the school’s 800 students, and that number, she reports, “is going up exponentially.” Although Spanish is the most common language spoken alongside English, 21 different languages are represented, including Ethiopia’s Amharic and Oromo, Nepali, Farsi, and Pashto.

Meanwhile, nearly 2,000 miles away, a new school year is beginning at Boston International Newcomers Academy (BINcA), a program within Boston International High School that, over the course of the year, will serve 500 students. According to Tony King, BINcA’s headmaster, 100 percent of the students are immigrants, representing 34 different countries and more than a dozen languages. As at Omar D. Blair, Spanish predominates, but large groups of learners speak Cape Verdean, Haitian, Somali, or Vietnamese.

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, I spoke to Karen and Tony about ways their schools incorporate next gen learning design principles to enhance the experiences of all students, including English Language Learners. In particular, they pointed to these key elements:

- Personalizing learning through student choice and agency

- Providing access to powerful and relevant learning experiences

- Building an inclusive and welcoming culture

Time for Language and Learning

Our opportunity and challenge is how do we shift toward project-based, student-centered learning while at the same time attending to the needs of students at the beginning levels of English proficiency?

—Tony King

Tony’s question highlights the time pressure all educators feel, but it is especially true for those who serve language learners. Given how scarce a resource time in the school day can be, tight schedules often squeeze out learners’ opportunities to make choices and participate fully in what the school has to offer.

To illustrate, Karen notes that Denver Public Schools requires all English Language Learners to receive at least 45 minutes of instruction in English Language Development (ELD) each school day. In the past, she says, “learners often had to make a big sacrifice to get the language support they needed. They had to give up something else, like pursuing their interests.”

Committed to giving all learners agency and choice, educators at Omar D. Blair rose to this challenge by rethinking the way they used time in the daily schedule. For example, Karen describes one new approach to ELD: instead of providing language support in isolation, ELD is integrated into science and social studies. Using digital learning platforms or, in some grades, co-teaching with Karen, educators provide the language support learners need but in the context of engaging with meaningful academic content. In this way, she explains, “there is no need to give up something else” in order to take an intervention-style language class. For instance, English Language Learners can now access advisory and pursue their passions for art, dance, or creative writing during the end-of-day activity block.

According to Tony, time is also a factor for the newcomers at BINcA, but he conceives of it more broadly—in years. BINcA students follow a personalized pathway through high school according to their needs—including language proficiency—but also based on their postsecondary goals. As he explains, “Many of our students are a year or two older than their grade level—they range from 14 to 21—due to interruptions in their education and differences in grade levels in the home country. And some who are older self-select to join grade nine.” For Tony, “Our philosophy is to have everyone stay as long as it can work for them and their family.”

For example, he tells the story of a recent graduate who is now attending Wesleyan University on a full scholarship. “She could have graduated after two years, but she chose to stay with us for four.” With a chuckle, he adds, “Our four-year graduation rate is very low, but that’s my fault. I am constantly convincing kids to jump out of their cohort. We go with what’s good for the kids every time.”

Responsive and Relevant Practices

Having collectively agreed and understood that the most powerful education we can offer is authentic and meaningful, how can we build the capacity to do that important work with students who are typically outside of that system?

—Tony King

When it comes to supporting English Language Learners’ engagement with authentic, culturally responsive, student-driven learning experiences, neither Karen nor Tony claim that their schools have all the answers. Both leaders cite areas for growth, such as extending real-world learning opportunities to more grade levels at BINcA or deepening partnerships with parents at Omar D. Blair. In Tony’s words, BINcA is “at the start of a long journey to give access to students who would not typically have access to powerful learning.”

Nevertheless, both schools have incorporated next gen learning elements that promote learner agency and frame bilingualism as a strength to build on in learning and life. Karen describes, for example, how a signature assessment practice at her school, student-led conferences, supports English Language Learners to take ownership of their learning and also take charge of communicating that learning to their families. For these conference events, Omar D. Blair Charter School deploys Spanish speakers among the staff or interpreters from Denver Public Schools, who provide free, in-person translation in over 160 languages. For 20 minutes, Karen explains, each student is empowered to take parents on a tour of work products, articulate their goals for learning, and share data on their progress. Karen reports that turn-out is very high, in part because “the parents of returning students get the word out” about how positive, meaningful, and welcoming the experience is.

The bulletin board near the main office at Omar D. Blair Charter School welcomes visitors in all 21 languages spoken by learners and their families. (Courtesy of Amanda Avallone)

For Tony, two events in 2017 catalyzed BINcA to embrace authentic, project-based learning for the newcomers they serve. One of these was a visit to Iowa BIG, a partnership of schools in his home state committed to real-world learning. The other was participating in a Mass Learning Excursion, sending a team to observe and engage with new designs for learning at innovative schools in and around San Diego. Mass Learning is a program of learning excursions for Massachusetts educators organized by NGLC with funding from the Barr Foundation. Tony recalls the effect of the visits this way: “All this awesome project-based work inspired me to think, ‘Let’s put kids to work as problem-solvers for the community.’ We started thinking of our students as people who could not just learn, but contribute.”

“We piloted with our seniors, organizing a pitch day where community partners and city departments talked to students about their challenges. From there, we designed a senior capstone experience for students to work with these organizations to solve a problem. It was a months-long project and really rigorous, with adult-level, professional research, surveys, and interviews with people in the community. The students then had to present back to the community group or agency about their proposed solutions.”

Tony tells the story of one capstone project, in which BINcA students partnered with English for New Bostonians, an organization that supports immigrants to learn English. The problem to be solved, he recalls, related to the curriculum they used to help parents communicate with their children’s schools: the English language materials were very much geared toward elementary school students. For the senior project, BINcA students helped their community partners rewrite the curriculum to include English that parents would need to ask questions, raise concerns, and discuss issues relevant to high school. Drawing from their experiences as high school students and language learners, the seniors were uniquely suited to solve this problem.

A Sense of Community and Belonging

We have lots of moms and aunties here. There are at least four pairs of eyes watching out for students whenever they walk down the hall. We really know the parents, and everyone has at least one person in the school they know is a safe person to talk to.

—Karen Lord

Born in Trinidad and Tobago, Karen emigrated 20 years ago and settled in Colorado. She now lives close to the school where she works. The immigrant experience, she says, has helped her support Omar D. Blair’s educators to provide culturally and linguistically responsive teaching. It also puts her in an ideal position “to advocate for kids and parents and teachers,” who are as diverse as the families they serve.

In addition, her knowledge of the community shapes her messaging about the relevance of what students are learning. “There are lots of business owners among our parents, so when we talk about our goals for students, we refer to how solving problems, being a lifelong learner, and making educated decisions can help them carry on their family’s legacy, as well as succeed in college, trades, or being a great parent.”

Parent engagement is still an area for growth, she says, “but it’s a real focus for us.” Greeters are stationed in the hallways to welcome families and visitors. The school also hosts cultural events to celebrate families’ dance, food, and music traditions, as well as staging a “wax museum where kids dressed up as a person they admire.”

Headmaster Tony King (far left) with BINcA students and staff at an Iftar celebration the school hosted during Ramadan (Courtesy of Boston International Newcomers Academy)

According to Tony, BINcA has also made parent engagement a priority. However, he points out that “what parent engagement looks like is different everywhere. When parents work two jobs, they are fully engaged—they are doing everything they can so their student has the conditions to go to school.” Recognizing the scheduling challenges parents may face, Tony recommends “giving a month’s notice of events so they can work it into their schedules. Being super flexible for families is how we can get parents in.”

One way BINcA engages parents is through celebrations of learning. For example, Tony describes one popular event: “a publication party at the end of a project, which might include a speech competition, food, kids standing on the stage reading a poem.” BINcA also hosts what he calls “purely community-building events,” like an Iftar meal during Ramadan, which, Tony points out, “attracted 75 people—and not just Muslim students, but families, staff, and members of the community.” For Tony, the message to parents is simple and clear: “We know who you are, and you are welcome in this school. We are your partners to help your kids get to where they need to go.”

Resources

- This portfolio presentation schedule from BINcA lists 11th grade project topics, with links to the students’ presentations and websites, along with their community partners. This senior project summary also identifies the many languages represented in the 12th grade projects.

- Culturally Responsive Teaching Matters, a resource from the Equity Alliance at Arizona State University, provides an introduction and overview of culturally relevant teaching practices.

- The website ¡Colorín Colorado! serves educators and families of English language learners in Grades PreK-12, providing free research-based information, activities, and advice to parents, schools, and communities throughout the U.S.

- This story about NGLC Learning Excursions explores the unique benefits of this kind of professional learning and provides resources for hosting one of your own.

Photo at top, courtesy of Amanda Avallone: Dance class at Omar D. Blair Charter School in Denver.

This article was updated on 9/19/2019 to correctly identify the name of the dance teacher at Omar D. Blair Charter School.