Co-Planning with Students: How Student Voice Builds Engagement and Buy-In

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

When students co-plan a lesson through a Student Research Day, they can become more invested, energized, and purposeful in their learning.

As educators, we plan carefully. We align standards, anticipate potential misconceptions, and design lessons that will foster understanding. Yet many of us experience a familiar frustration: students complete assignments, follow directions, and still struggle because the learning does not connect. In my 7th-grade science classroom, students often failed assessments not because they lacked ability or effort, but because the content felt disconnected from their lives. The students could complete tasks without internalizing ideas, explain definitions without meaning, and move on without understanding why the learning mattered. The issue was not rigor. It was ownership. Students were completing assignments, but they were not yet positioned as co-owners of the learning.

Why Student Voice Matters

Because I teach for a highly diverse student population within my district, I sought instructional strategies aimed at increasing student engagement across varied learning needs and backgrounds. In this process, I examined the insightful practices of Christopher Emdin, who, among his vast experiences, authored For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education. In this book, Emdin emphasizes the role of student voice and agency in creating meaningful, engaging classrooms. When students are treated as contributors rather than passive recipients, learning becomes something they help build rather than something that happens to them. Co-planning with students does not mean students decide everything. It means they help shape how learning happens while teachers remain responsible for what students must learn. In my classroom, co-planning became the bridge between rigor and relevance.

The Problem: Comprehension without Ownership

Before co-planning, instruction followed a traditional structure of teacher explanations, guided practice, and independent work. While this worked for some students, many struggled to fully grasp abstract scientific concepts. Engagement dipped when lessons felt disconnected from students’ lived experiences. The issue was not motivation. It was ownership. Students did not always see why the learning mattered or how it connected to their lives.

The Shift: A Structured Student Research Day

Co-planning in my classroom begins with a student research day built intentionally into daily instruction. Students independently research real-world applications of a concept and connections to issues in their community or personal lives. This process is structured and aligned to the learning target and standard. Students are not researching random topics. They are exploring multiple ways to make sense of the same content.

Student voice shaped instruction without compromising expectations.

At the end of the research period, students submit three pieces of data: which resource helped them understand the concept best, which application or connection felt most meaningful, and one lingering question they still have. This step functions as both formative assessment and metacognitive reflection, giving students a voice while providing teachers with valuable instructional data.

Co-Planning in Action: Using Student Data to Plan Instruction

After reviewing student responses, we vote. The vote does not determine the standard, assessment, or learning target. Instead, it helps determine which context or example we center, which resource or activity we use, and whether the next lesson focuses on re-teaching or extending understanding. For example, during a unit on mutations, students in different class periods identified different entry points that helped them understand the content. One class voted to use a PhET simulation to visualize how mutations occur and affect traits. Another class chose to focus on sickle cell anemia, citing family connections and a desire to better understand a condition they encounter in their own lives. Both classes addressed the same standard and engaged in rigorous scientific thinking. The difference was the path we took to get there. Student voice shaped instruction without compromising expectations.

During a co-planning session, Cylie Schulz took ownership of locating an instructional resource and discovered a PhET simulation that aligned closely with the learning target. Through this process, she recognized how the resource supported her own learning needs. “I learned more because I feel like I learn by physically doing and seeing things happen,” she shared. Her reflection highlighted an important insight: when students are empowered to select resources that match their learning styles, comprehension deepens, and abstract concepts become tangible.

Similarly, Tucker B. Cook suggested refining the lesson structure to make it more competitive. Reflecting on the change, he explained that he preferred this approach because “it was a really cool lesson for teaching because it was fun.” For Tucker, the competitive element didn’t reduce rigor—it increased engagement and motivation, making the learning feel purposeful rather than procedural.

When Student Voice Becomes Student Leadership

In some cases, student voice extends beyond shaping the lesson and into helping teach it. When students have a strong personal connection to a topic and demonstrate clear understanding, they are sometimes invited to lead a short mini-lesson lasting no more than ten minutes. This is always optional, structured, and carefully supported.

These moments do more than increase engagement. They signal to students that their knowledge, experiences, and voices have value in academic spaces.

Before leading, students meet with me to plan. We clarify the learning target, key vocabulary, and the scientific idea they will explain. Students are not responsible for introducing new content or assessing peers. Instead, they might explain a real-world application, walk the class through a visual or example, or share how a concept connects to their lived experience.

For example, during the unit on mutations, students who selected sickle cell anemia due to family connections helped explain how the mutation affects red blood cells and why that matters biologically. Their role was not to replace instruction, but to add depth and authenticity to it. I remain present to clarify misconceptions, ask probing questions, and connect their explanation back to the standard.

These moments do more than increase engagement. They signal to students that their knowledge, experiences, and voices have value in academic spaces.

Guardrails That Protect Rigor

A common concern about student voice is loss of control. That concern is valid unless clear guardrails are in place. In my classroom, state standards, learning targets, required scientific vocabulary, and measurable assessment expectations remain non-negotiable. Student choice exists within bounded options, and every option leads to the same learning outcome. When students suggest ideas that lack depth, I do not shut them down. I ask questions about how the idea supports understanding of the science and what evidence would strengthen it. This approach maintains academic rigor while honoring student contributions.

The Impact of Co-Planning on Student Ownership of Learning

The impact of co-planning was immediate. Students began explaining scientific concepts using examples they had experienced themselves. Class discussions became more energizing and purposeful. Written responses showed stronger reasoning instead of memorized definitions. Most importantly, student apathy decreased. Engagement increased because students recognized their own thinking reflected in instruction. Student voice did not replace my teaching. It strengthened it. Co-planning with my students helped me connect in ways that I likely would not have been able to due to different demographics.

Why Co-Planning Works

Co-planning works because it shifts learning from compliance to collaboration. When students have a voice, they are more invested in understanding the material and more willing to struggle productively. This approach does not lower expectations. It increases access. When students can connect content to their own lives, comprehension follows.

Actionable Steps: Try a Student Research Activity to Inform Your Next Lesson

- Build in a five- to ten-minute research or reflection window aligned to the learning target.

- Ask students which explanation, example, or context helped them understand the concept most and where confusion still exists.

- Collect and review this input as formative data rather than feedback to file away.

- Use student responses to decide how the next lesson is structured, which context is centered, or whether re-teaching or application is needed.

- Keep standards, learning targets, and core skills non-negotiable while students help inform the path to mastery.

A Challenge for Educators

Choose one lesson next week and identify one decision students can help inform, such as the example you use, the resource you select, or the way students practice the skill. Collect student input, act on it, and observe what changes. Co-planning with students doesn’t mean giving up control. It means sharing ownership of the learning.

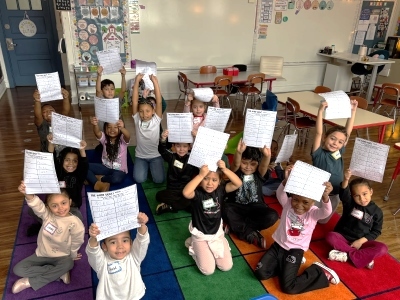

Photo at top by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC 4.0