Cracking the Code on K–2 Literacy Using Manipulatives

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

A phonics-focused walkthrough and coaching process is making sure K-2 students are building the neural pathways required to move from learning to read to reading to learn.

At the heart of every successful educational journey is a fundamental milestone: the transition from learning to read to reading to learn. Research indicates that third grade is the critical pivot point for this shift; it is the moment when the 'scaffold' of literacy instruction is removed and students are expected to use reading as a tool for all other subjects. If a student isn't properly equipped with a strong phonics foundation by this stage, it impacts more than just their reading score—it creates a cognitive barrier that can hinder their access to the entire fourth grade curriculum and beyond. This is why immediate, data-driven pivots in the K–2 years are non-negotiable. The English code is complex, and 'cracking' it requires a fundamental shift in the classroom dynamic: moving away from students simply listening to a teacher and toward students actively doing the work of a budding linguist.

In order for our youngest learners to build a permanent foundation for literacy, we are implementing a new phonics walkthrough centered on the practices that support orthographic mapping and the intentional use of manipulatives at Distinctive Schools. Here is how we shifted our instructional coaching from high-level observation into phonics walks: a targeted, research-based coaching model designed for K–2 students to have the right tools necessary for deep learning to take place.

The Why: Orthographic Mapping and Cognitive Load

Orthographic mapping is a cognitive process of mapping the spelling of a word to its pronunciation and meaning. Think of it like the glue that sticks the word into the memory.

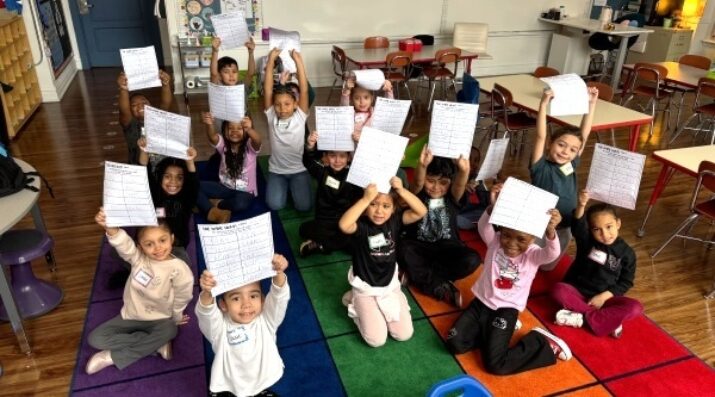

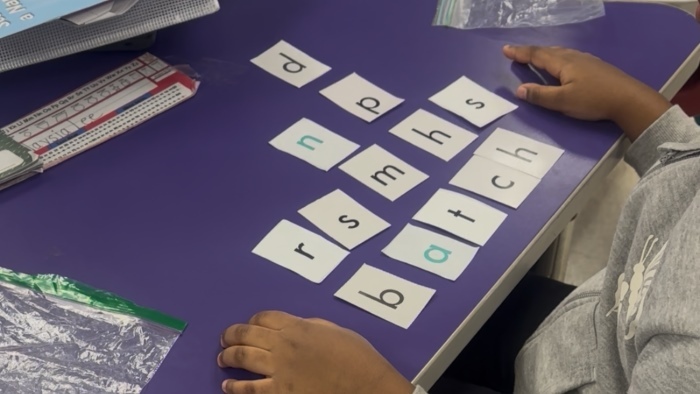

We focus heavily on the use of manipulatives—like letter tiles—to help reduce cognitive load. When a child is first learning a sound, asking them to identify the sound, recall the letter shape, and physically write it down simultaneously can overload their working memory. By providing letter tiles, we allow them to focus solely on the relationship between the sound and the symbol. When students have the opportunity to use manipulatives to build words, they are strengthening their ability to read words. This provides an essential scaffold; once that connection is secure, we bridge to encoding (writing) without the mechanics of handwriting acting as a bottleneck to literacy.

The Shift: From Oral Blending to Active Encoding

Imagine a classroom where students collectively echo their teacher but when the lesson ends, half the students still can’t tell you how the word “cat” is built. Oftentimes, teachers do the heavy lifting for the students; while students were participating in oral blending exercises, they lacked the consistent, hands-on practice needed to deeply and meaningfully internalize the work.

To address this, school leaders and I launched a targeted professional development cycle for teachers to begin putting the onus back onto students:

The Baseline: Our initial walkthrough revealed that less than half of students were using manipulatives during phonics blocks. Most instruction was teacher-led and oral-heavy.

The PD Intervention: We facilitated a 90-minute intensive session focused on the mechanics of blending and building. We broke down the critical difference between blending for decoding (reading) and blending for encoding (spelling or word building) and created a course of action for hands-on practice.

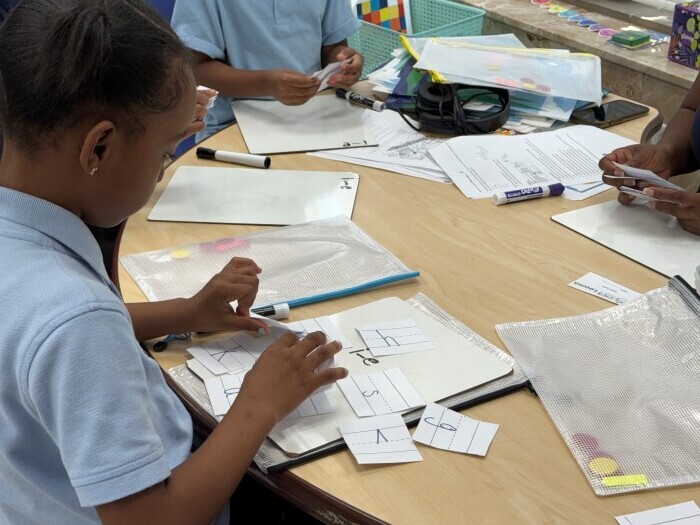

The Goal: Every K–1 student would use physical letter tiles, while 2nd graders would utilize whiteboards for rapid encoding practice.

This shift in practice is a fundamental pivot toward instructional equity. When students only participate orally, it is easy to fall into the trap of collective competence, where the loudest voices lead and struggling learners simply mimic their peers. By incorporating the use of manipulatives consistently, we make the learning visible. We effectively unblock the "cognitive bottleneck" that occurs when a child tries to juggle letter sounds, letter shapes, and the fine motor skills of handwriting all at once. By removing those competing demands, we allow the brain to focus entirely on this orthographic mapping. This means every student isn't merely getting through a lesson, but is actually building the neural pathways required to move from learning to read to reading to learn.

Implementing Phonics Walks

When school leadership teams and I enter a classroom, we are not only looking for "engagement" but specific instructional routines. A "Phonics Walk" rubric focuses on:

Student Lifting: Are students physically moving tiles or writing, or are they simply repeating the teacher?

Materials Management: Are manipulatives prepped and accessible? (e.g., K–1 letter tiles in organized baggies).

Instructional Precision: Is the teacher following a proven, research-based routine for blending and segmenting?

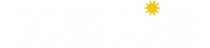

The impact of this shift was immediately visible. During our follow-up walkthroughs, we saw classrooms transform from spaces of passive listening to laboratories for “code-breakers.” We observed students leaning into their autonomy, not waiting for prompts but instinctively referencing alphabet cards to make independent connections. When tasked with replacing a letter to read a new word, learners actively employed strategies like finger taps to isolate sounds and scanning the room to retrieve the right letters needed to build and decode new words.

Like any new initiative, there are still refinements to be made, like turning these new routines into everyday habits and providing additional support for teachers who need some extra coaching on their delivery of instructional practices, but these early results are promising and—most importantly—students are feeling excited by learning. By focusing on these technical, research-based routines in the early years, we are ensuring that when our students reach the upper grades, they aren't struggling to decode the page—they are able to learn from it.

All photos courtesy of Distinctive Schools.