How Sensory Language Gives Students a Safer Way to Name Emotions

Topics

Together, educators are doing the reimagining and reinvention work necessary to make true educational equity possible. Student-centered learning advances equity when it values social and emotional growth alongside academic achievement, takes a cultural lens on strengths and competencies, and equips students with the power and skills to address injustice in their schools and communities.

When students are introduced to the sensory language of taste, they are able to name complex emotions and can develop greater emotional fluency.

We often ask students what they see, hear, and feel—but how often do we ask them what learning tastes like? Sometimes the hardest feelings to name are the ones we can taste—the sweet wins, the sour moments, and the bitter lessons that linger.

In my classroom, Thursdays have a flavor. That wasn’t something I planned. It started quietly, almost by accident. I noticed that by the end of the week, students carried a lot with them—small frustrations, quick victories, moments that didn’t fit neatly into a check-in chart or journal prompt. When I asked how they were doing, answers stayed surface-level. “Fine.” “Okay.” “Good.” But when I asked a different question—What does today taste like?—something shifted.

Thursdays are the days we pause, check in, and notice how the week feels—one taste at a time. When I ask students to name their taste of the day—sweet, sour, or bitter—they don’t hesitate.

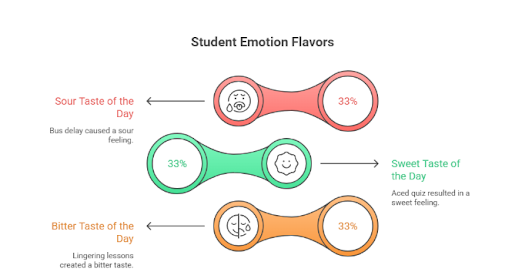

One says, “Today’s sour. My bus was late.”

Another says, “Mine’s sweet. I aced my math quiz.”

In less than two minutes, the room fills with honesty, humor, and connection. No lengthy journal prompts. No rating scales. Just flavor.

We use sight, sound, and movement constantly to support social-emotional learning (SEL)—but taste? That sense rarely makes it past lunchtime. Yet it’s one of the most powerful entry points to emotion and memory. Sensory language brings taste back—not through snacks, but through metaphor—helping students name feelings, spark empathy, and reflect together.

And it’s easier than it sounds.

Why Taste Helps Students Understand Emotions

Taste is the only sense directly tied to both memory and emotion. A single flavor can pull up a moment—that first sip of cocoa on a cold morning, the crunch of popcorn at a movie night.

When we link taste to SEL, we give students an emotional shortcut. Saying “today feels bitter” or “this moment was sweet” is often easier than saying “I’m disappointed” or “I’m proud.” The language lowers the barrier. Students answer faster. There’s less overthinking, less watching the room to see what others might say. They pick a word and go with it.

It’s also universal—everyone knows what sweet or sour feels like. Once students grasp the metaphor, they begin building a deeper emotional vocabulary without worksheets or mood charts. For students who struggle to label emotions directly, sensory language becomes a bridge—familiar, concrete, and safe.

Most teachers already hear this language in their classrooms. Students talk about “sour days,” “sweet wins,” and “hard lessons.” This practice doesn’t introduce new words so much as give permission to use the ones students already carry.

Why Once a Week Reflections Are Enough

I used to try daily reflections. I thought more would mean better. It didn’t.

What I learned is that less is more. By Thursday, students have lived a full week—moments that lifted them up, moments that challenged them, moments they didn’t see coming. That distance matters. It gives the reflection weight.

Some Thursdays are quiet. Some days the room leans bitter and stays there longer than I’d like. I don’t rush those moments. I notice them. The consistency matters more than the outcome.

Thursdays have become a shared breath—a rhythm between learning, where we stop chasing the next task and notice where we are.

Sensory language gives students a voice—a way to pause, connect, and reflect in a world that rarely slows down.

How Sensory Language Looks in Practice

Here’s how sensory language takes shape in my classroom:

Thursday Flavor Forecast

Every Thursday, students name their taste of the day—sweet, sour, or bitter. The three-word check-in takes about a minute, but it opens space for empathy and conversation.

Tasting Partners

Students pair up for a quick share. Each conversation includes one taste-related question and a few low-stakes prompts—a favorite food, an animal they like, a moment from their week, or something from our school garden, where we’ve grown tomatoes, carrots, and herbs together. These easy entry points help every student participate.

Savor the Story

During reading or discussion, I ask students to describe a moment’s flavor. Was the ending sweet? Was the decision bitter? Was the discovery sour but necessary? Abstract ideas become tangible. One student once said, “That decision was sour, but fair.” That kind of emotional reasoning sticks.

Table Talk

Some of our richest conversations come from food memories tied to family or tradition. These stories build belonging and highlight the beauty of our differences—one flavor at a time.

Mindful Bite

When food is allowed, we slow down for a single intentional taste. Students describe texture, warmth, or surprise and connect it to a feeling. Most of the time, though, sensory language stays metaphorical—which keeps it doable in any classroom.

The Ripple Effect into Greater Emotional Literacy

Over time, students begin using taste words on their own.

“That quiz was sour.”

“This week feels sweet.”

A few weeks in, I noticed something else. I stopped being the one asking the question. Students started checking in with each other before class even began. Not every day. Not perfectly. But enough that it stood out.

These moments signal emotional fluency. Students are identifying and articulating feelings without needing a prompt. Once they understand that everyone’s “taste” can be different, empathy grows. I hear them ask each other, “What made your day feel bitter?” That’s compassion in action.

For me, these check-ins reveal more than any chart or rubric ever could. When a student’s “taste” stays bitter for a few weeks, I know it’s time to reach out.

Why Teachers Can Use Sensory Language Today

Teachers often say they want SEL that’s simple, real, and quick. That’s exactly what this is. You don’t need materials or prep—just three words: sweet, sour, bitter.

It works across grade levels and subjects. Younger students might draw their “taste.” Older students might connect it to a text, quote, or current event. The language meets them where they are.

The Lingering Taste of Emotional Learning

I hesitated to write about this at first because it sounds almost too simple. But the longer I teach, the more I trust the practices that last because they don’t demand attention—they make room for it.

Sensory language gives students a voice—a way to pause, connect, and reflect in a world that rarely slows down. It reminds us that emotional learning doesn’t have to be scripted or complex. Sometimes, it starts with a flavor, a feeling, and a shared space to listen.

When students name their taste of the day, they’re not just talking about food. They’re showing us how life feels—one bite, one word, one Thursday at a time.

All images courtesy of the author.