It’s Time to Roll with Polyhedral Pedagogy

Topics

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Evidence suggests that tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs) can transform learning. One Kentucky teacher is demonstrating the advantages of instructing with TTRPGs.

“You Walk Into a Classroom…”

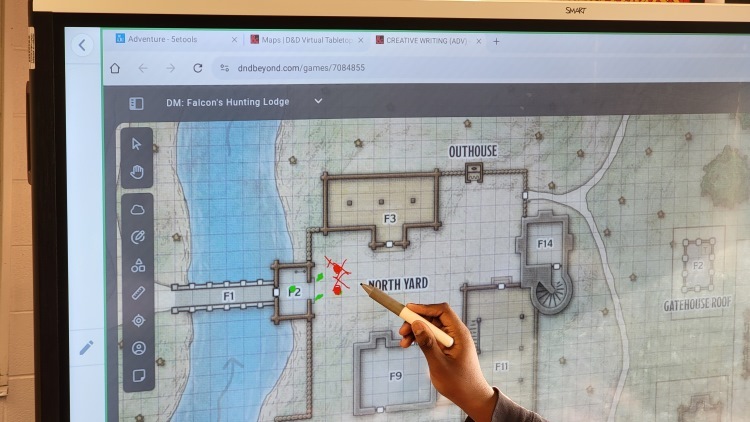

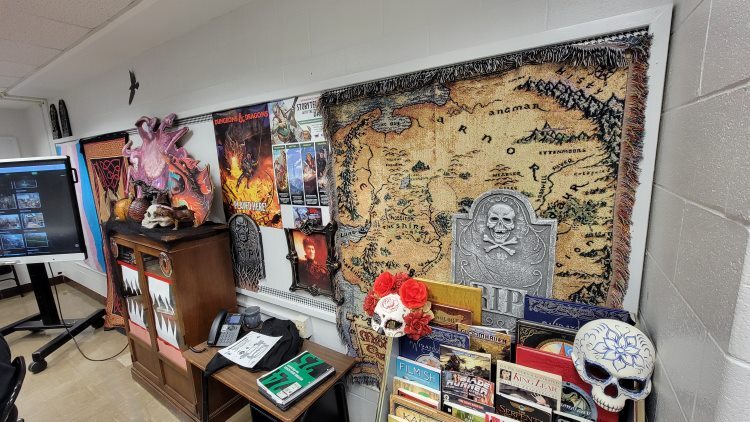

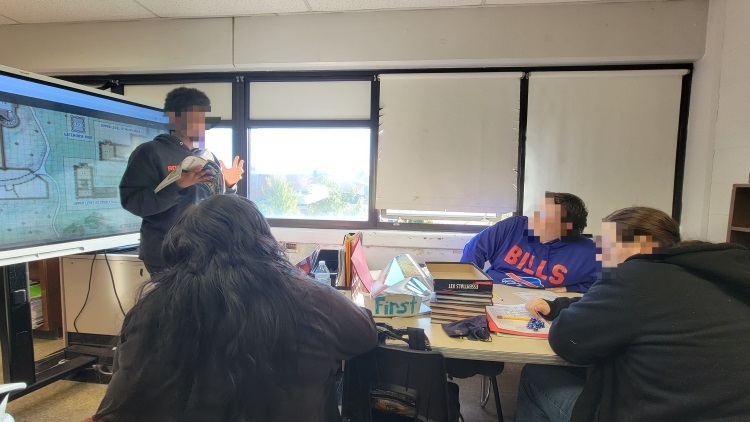

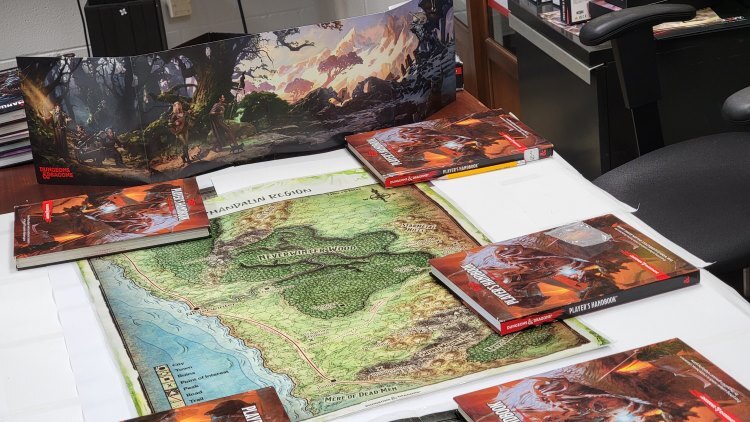

It’s an October 2025 morning at Western High School (“The STEM Magnet”), part of the Jefferson County Public School (JCPS) district, located in the southwest end of Louisville, Kentucky. As I arrive into Sterling Harris’s classroom a few minutes past the bell, I’m greeted by his warm smile and handshake, but also by the unblinking eyes (all eleven of them) from a Beholder monster, and a glass-doored bookshelf that, if the white fanged teeth are any indication, is actually a Mimic in disguise. As I find a seat in the corner, Harris is starting class with some housekeeping directions. “For those working on the opening of your short story today, make sure to write more than one paragraph. And be descriptive! What do I mean by descriptive?” A student raises his hand and answers, “You need to paint a picture with your words so you can see it in your mind.” “That’s right!” Mr. Harris affirms. “Let’s get into today’s groups.” One third of the students head to a table closest to the monsters, where Harris will transition from teacher to Dungeon Master, or DM for short, so their quest can begin. In the back, a student DM stands in front of a mobile flat panel touchscreen, plastic stylus in hand, prepared to annotate a castle map as players sit and settle. The remaining third of the students are going on a writing journey, some staying in their desks and some collegially surrounding a table in the middle of the room; they may pull out Chromebooks instead of polyhedral dice, but the students are no less ready to roll. Clearly, this is not a traditional creative writing class. It’s creative writing with Dungeons & Dragons.

This visit was not the first time I’ve met Harris, or been to Western High School. Indeed, I’ve been privileged to get to know Harris and the school over the last few years. Western had 372 students in 2024-2025; three-fourths were African-American and Hispanic/Latino, 83.9 percent of the students were considered economically disadvantaged, 12.7 percent were ELL, and 18.5 percent had disabilities. (These statistics are higher than the district and/or state average.) The school recently completed renovation of some classroom space into an eSports arena, and I spearheaded a road trip full of educators from around Kentucky to marvel at the space and admire the school’s Digital Design and Gaming Development pathway that utilizes it on a day-to-day basis. As for Harris, he volunteered as one of my educator players for a “TTRPG Telethon” I helped organize, and I also came twice to watch Harris DM his Dungeons & Dragons—often abbreviated as D&D—“flex course.” Western’s flex courses of various interests and topics provide students the opportunity to meet periodically during an instructional day. This ensures all students have a chance to participate, avoiding issues that can arise from a traditional “afterschool club,” like staff time and student transportation. The popularity of Harris’s D&D flex course led to his D&D creative writing elective, with a roster containing freshmen through senior students.

“We love seeing more and more students get the chance to engage in something they love through our embedded Dungeons & Dragons flex course,” says Melanie Santiago-Weaver, Western’s principal. “Mr. Harris has transformed his passion for D&D into a creative writing class, allowing students to strengthen their literacy skills while exploring their love for storytelling and imagination.”

Santiago-Weaver’s encouragement of her staff to transform learning, while still grounding such innovation in solid pedagogy, is not to be underestimated. It’s a refrain you will hear from others, explaining what is necessary to shake off the shackles of traditional instruction. Erin Malcolm, an English teacher at Blackstone Academy Charter School in Rhode Island, created a game around The Great Gatsby, where “learning challenges [are] levels, rather than . . . final assessments.” Malcolm “can do this because of Blackstone’s trust in teachers like her, to build a curriculum where students feel safe to aim high, and just as safe to fail.”

This intentionality of parallel pedagogy is important to note; if we want students to “fail forward,” we need admin to instill that belief in their teachers. And there is an urgency to build such transformative fail-forward learning spaces now, both for the students and for the teachers that teach them, particularly in the post-pandemic precipice we find ourselves standing on.

An Antecedent of Acronyms: Defining D&D, TTRPGs, and KyEdRPG

We will return to Sterling Harris and his students in a bit. But first, let’s talk about the fantasy-themed game that is a core element of their classroom. Dungeons & Dragons was created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in 1974. It is not only the world’s first tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG), but also remains the most popular. D&D’s pop culture dominance has now spanned more than a half century, proven recently by the success of the 2023 film Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, and how it is the emotional and narrative heartbeat of the Netflix hit series Stranger Things, which just streamed its final season. If that wasn’t enough, D&D has entered, as NPR put it in the title of their 2025 story, its “stadium era;” groups like Dimension 20 have done live gameplay of D&D in front of 20,000 fans, screaming as if they are at a rock concert, selling out New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Slow your roll, I hear you saying. What are TTRPGs?

At its core, a tabletop role-playing game is a co-created story. Players assume the roles of characters (player characters, or PCs) who are joined by a “referee” (the Game Master, or GM; in D&D specifically, this is called a Dungeon Master or DM) that plays all of the non-player characters (NPCs), frames a narrative of the story’s world, and adjudicates on the game’s rules. Depending on the TTRPG, these rules can be light or heavy, and are usually governed at some point by the rolling of dice to determine whether an outcome is a success or a failure, often modified for better or worse by a character’s abilities and situational context. It’s more improv theater than a scripted play, since the ending of the story is not pre-determined, and all of the players are influencing what happens in real time. While the genres of fantasy, sci-fi, horror, and superheroes are predominant, TTRPGs come in a wide variety of settings, and could easily be adapted into whatever story the players wish to tell. In short, TTRPGs are immersive, collaborative, and fun.

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that TTRPGs were nurtured in me almost from the womb. I’ve been a public school educator since 2005, first as a high school English teacher, then a district coordinator of digital learning, and most recently, as a digital learning consultant for the Ohio Valley Educational Cooperative (OVEC), which serves 14 districts in and near Louisville encompassing over 150,000 students. But way before that, I was born in 1974, the same year as D&D. I became a fan of fantasy and sci-fi books, television, and films at an early age, so it’s perhaps no surprise that I enthusiastically played D&D and other TTRPGs in its golden era of the 1980’s, the same time setting of Stranger Things.

As I got older, TTRPG sessions became more infrequent. But I never forgot the joy I experienced in the friendship theater of collective minds, imaginatively playing roles and rolling dice to play. Therefore, I saw the possibilities TTRPGs could bring in a learning space. As a classroom teacher, I incorporated simulations and game-based learning. While I was a district leader, I personally started to collect articles and videos about the positive impact of TTRPGs in educational and therapeutic settings. I began to envision a website where I could not only curate resources and research helpful for K-12 learning, but celebrate educators both inside and outside of the Bluegrass who were implementing TTRPGs. With that mission in mind, I launched Kentucky Educators for Role Playing Games (kyedrpg.com) in 2022. As the website grew, the idea for writing a book began; almost two and half years later, Tabletop Role-Playing Games in the Classroom: Infusing Gameplay into K-12 Instruction was published (McFarland, 2025).

I champion “Polyhedral Pedagogy,” a phrase that encompasses all the ways an educator can integrate TTRPGs into learning spaces. In one of my frameworks, I break down four types of “Depth of TTRPG Infusion:”

Adjacent Infusion: extracurricular “pure gameplay” at a school but outside of instructional time, such as during a summer camp or Harris’ flex course

Elemental Infusion: a learning activity that has an aspect of TTRPGs but is just short of playing a game, like a character sheet lesson where a student creates the stats of someone from history or literature and defends their choices

Episodic Infusion: playing a TTRPG “one shot” as part of a lesson plan

Full Infusion: when TTRPGs are the DNA of an entire class or school, like Sterling Harris’ creative writing course

You might be asking: Polyhedral Pedagogy sounds fun, but can it positively impact learning? A fair question, and to both answer that question and put it in a local context, let’s turn to the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) and what it calls “Vibrant Learning.”

Vibrant Learning and the Scholastic Validity of TTRPGs

Kentucky’s Commissioner of Education, Robbie Fletcher, recently announced public school accountability data for the school year 2024-2025. We’ve made some incremental academic improvements on state assessments, which is worthy of praise, but pervasive challenges persist. For example, student chronic absenteeism was 25 percent for 2024-2025. This sobering number looks better when put in comparison to 30 percent chronic absenteeism in 2022-2023. Yet it still reflects that 1 out of 4 Kentucky students currently struggle to even show up, missing 10 percent or more of their time in school. What kind of instruction do they face when they arrive? What kind of instruction will keep them coming back?

After a series of community town halls around the Commonwealth in spring 2021, KDE took what stakeholders shared as an imperative to innovate learning. In the fall of that same year, KDE announced their “United We Learn” initiative, “our vision for the future of public education in Kentucky.” “The heart of Kentucky’s United We Learn vision” is Vibrant Learning Experiences (VLEs), “powerful moments when learning is meaningful, engaging, and connected to real life. They move beyond traditional classroom instruction to spark curiosity, creativity, and collaboration.” The emphasis of VLEs in classrooms across the Bluegrass over the last four years may very well be one reason we are inching upward in many metrics.

Does Polyhedral Pedagogy fit within VLEs? While a TTRPG can certainly repackage content facts and figures in a new way, its real strength lies in its immersive power to create meaningful, engaging student experiences. The roles students play offer both mirrors and windows, instigating natural reflection on a perspective that can connect to their own world or allow them empathy into another’s. A well-designed TTRPG is full of kindling—wonderment, puzzles, and problems to solve, and the need to productively work together—ready to alight from the players’ sparks of curiosity, creativity, and collaboration. In fact, KDE includes a VLE example from Justin Gadd, a middle school teacher at Marnel C. Moorman (Shelby County), titled as “Joyful Learning Through Tabletop Role-Playing Games.”

Part of that joy can be leaning into the human-centered, analog aspects of TTRPGs, which often only require paper, pencils, and dice, although digital tools can play their part. It is a blended aesthetic that John Spencer defines as “vintage innovation:” “the overlap of old ideas and strategies with new technology, contexts, and knowledge” that “is intentionally both/and.” In Harris’ class, such “both/and” was prominent. Alongside the physical dice, printed rulebooks, and paper character sheets, there were also touchscreen flat-panel monitors utilizing digital tools like annotation software, D&D Beyond, and Tabletop Audio. (As Harris pointed out, such technology use by Western students should not be a surprise—it is a STEM Magnet school, after all!) And while Spencer doesn’t discuss TTRPGs specifically, he praises the general use of games in school for several compelling reasons, such as how they increase engagement, help with “higher retention of the content” leading to “deeper, more permanent understanding,” and “make connections between concepts and ideas” that “bridges the abstract and the concrete.”

Educators at a recent Dungeons & Desks professional learning session.

Scholastic validity of TTRPGs as a part of instruction is spreading in academia. There are journals such as Analog Game Studies, Board Game Academics, and The International Journal of Role-Playing Games publishing new and emerging research. I personally have contributed educational TTRPG stories to books like Dr. Karin Hess’s Applying Depth of Knowledge and Cognitive Rigor (Teachers College Press, 2025) and Urgent Care for Educators: Situating Responsibility as a Way for Educators to Transform School Cultures (Brill, 2025, edited by Dr. Barbara J. Smith), as well as a 2023 article here at NGLC. Since the spring of 2025, I’ve partnered with Kalli Colley—a regional innovation specialist with KDE, and at least as importantly, a former social studies middle school teacher who used TTRPGs in her own classroom—to facilitate an ongoing professional development series on Polyhedral Pedagogy. The series has proven to be popular and transformative for its participants. As one educator shared, “I would absolutely recommend this training. It has given me easy to use activities that I can apply in the classroom to make lessons more engaging without taking away the rigor,” an affirmation of the best qualities of vibrant learning.

Educators at a recent Dungeons & Desks professional learning session.

From such generalities of the power of TTRPGs in school, let’s now use Harris’ creative writing course to explore how Polyhedral Pedagogy can impact three specific areas: academics, social-emotional learning (SEL), and durable skills.

TTRPGs, Academic Content, and Rigor

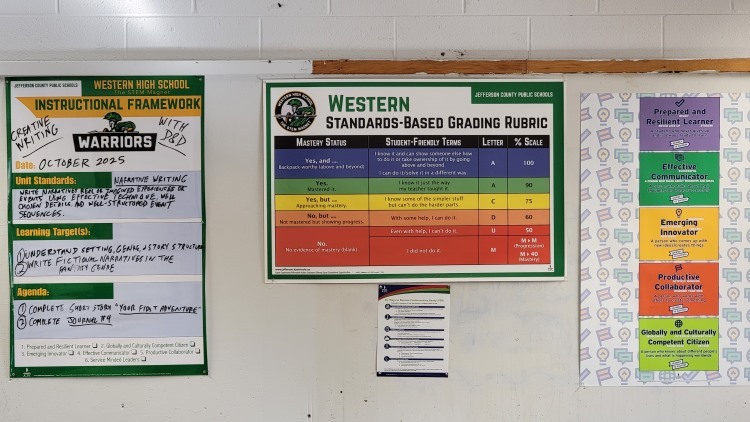

For Harris, grounding his class in academic standards is a non-negotiable. I was pleased to see a visual reminder of this in the “Instructional Framework” poster on the classroom wall with his current unit’s Narrative Writing objectives. These are from the same rigorous Kentucky Academic Standards required of all of our students.

In the first week of the course, students created the stats and the backstory of an original character. From there, the personalized instructional needs of the students, and his unit objectives, determine next steps, as students build up their writing ability to develop longer, higher quality narratives. Harris still utilizes traditional approaches when appropriate, perhaps teaching a mini-lesson on a particular writing skill, or facilitating some other whole-class activity based on the assessed needs of the students. On a typical gaming opportunity day, the class is roughly split into thirds and students are either playing D&D or writing. Students that are more experienced with D&D play in a student-led group, while Harris leads novice players. Groups cycle so that a gameplaying group on Day X will be writing on Day Y and vice-versa.

Sterling reminds students their writing is not meant to be a factual narrative of what happened when they gamed; this isn’t a journalism class, and “you guys aren’t journalists, you’re creative writers.” Instead, the gameplay should inspire later writing, or even put creative ideas from a prior writing session into practice. For example, at the start of the course, Harris instructed the students to include descriptive detail in their character backstories, “painting a picture with words.” This became a mantra for students (as the student at the start of this article demonstrated), not only to be more specific and detailed for the sake of a character sheet or when describing their character’s action in gameplay, but also for elaboration in their increasingly longer pieces of writing.

Students experience peer feedback not only in the traditional sense of trading papers after completing a draft (Harris calls them ”proofreading partners”), but in the act of co-collected storytelling of a TTRPG session; they learn during the adventure by hearing how others build cohesive narrative or add a dramatic flourish. Reflections, particularly after game sessions, are highly important as students complete journal entries. How would they summarize the key points of today’s gameplay? How were all of their senses engaged? What would they have done differently?

Students learn to view creative writing as a body of collective work, in various modes and modalities. They also see writing as an ongoing craft, with practice toward long-form narratives, which can be viewed by both teacher and students as assessments for learning (formative), assessments as learning (reflective metacognition), and assessments of learning (summative). Therefore, rigor is maintained in Harris’ course as the students’ creative writing improves in both quantity and quality, grounded in authentic purpose as they go into and out of gameplay. Imagination is not an abstract concept, mentioned but never truly practiced or applied. Instead, imagination is cross-nurtured for Harris’ students, through both their ongoing writing and in their playful trampling through the terrain of fantasy forests and dungeons.

As I said before, TTRPGs also provide a unique way to contextualize and contain academic content, and therefore establish authentic learning—something John Spencer noted when discussing what games in general can do in a classroom. It’s also important to emphasize that Polyhedral Pedagogy is not merely for ELA courses, nor is it limited to secondary students. All grade levels and contents, and all students—whether they have disabilities or are designated as gifted and talented (or both!)—can benefit, given the right intentionality and scaffolding. In classes utilizing TTRPGs, students aren’t simply passive recipients of historical and scientific facts, but can actively experience history and science. Formulas are not just calculated for plugging and chugging, but become algebraic spells to save the day. Students are not merely consumers of the fictional narratives of others, but create their own.

TTRPGs can also allow students to experience situations that might otherwise be difficult to replicate, and here, we can learn from a related digital perspective. Stanford’s Jeremy Bailenson created a way of determining when virtual reality might best be employed in education in what he called—I’m not making this up—the DICE Framework. As quoted by Rachelle Dené Poth in her 2025 book What the Tech? An Educator’s Guide to AI, AR/VR, the Metaverse and More, “Virtual spaces should be used when a learning experience is: too Dangerous (experiencing war), Impossible (going back in time), Counterproductive (inhaling carbon monoxide), or too Expensive (traveling abroad).” We can see how Polyhedral Pedagogy can borrow DICE’s rationale to also justify a TTRPG instructional experience. However, TTRPGs have two potential advantages over VR: much lower startup cost, and an analog respite in an increasingly digitized, AI-heavy, disconnected world.

TTRPGs and SEL

It is a TTRPG’s ability to connect students around a tabletop instead of a laptop that also gives it power in a school setting. When we look at the CASEL Wheel, it becomes quickly evident how self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationships skills, and social awareness are so necessary, and well-practiced, during a face-to-face Polyhedral Pedagogy experience. We need each other, and the best version of ourselves, to be highly successful at TTRPG gameplay. While students are storming castles, they are weathering the CASEL competencies.

When I visited Harris’ classroom, I was particularly impressed as I observed a student DMing for his peers. What better example of a student-centered learning space than a student-led TTRPG, where strong relationships, trust, and emotional intelligence are required for such a session to succeed? Seeing the CASEL competencies in action was also apparent in the agentic nature of the students; Harris requires students to be mindful of where they are in their work and manage their learning journey accordingly. Some students may sit out a gaming session because they need to catch up on an assignment (or made gently aware of this need by Harris); others ready to move on may choose to be creatively enriched with more gameplay. Both the instructional and SEL needs of the learners weave into a wondrous spell: students play to inspire their writing, and they are motivated to write in order to play.

One of the best by-products of playing TTRPGs, according to Harris, is that you “develop a certain confidence. You see a kid who's been playing D&D [for a period of time], and you see a confidence that they developed that they did not have when they first started playing. And it's a confidence that I think comes from facing challenges and overcoming those challenges. And no, they're not real challenges. That's not a real dragon, it wasn't a real band of orcs [you defeated], but you still did it. There is a certain joy that comes across when they're in the middle of a fight, it’s down to one roll, it almost could go the other way, and they roll a crit. They lose their minds . . . And the experience of that, I just think it builds this confidence, it builds a joy, it builds this camaraderie in the group that I think they take with them, you know, wherever they go from there.”

Like many schools, Western has a PBIS (Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports) system. Students earn points for making good choices and then can spend their points at Western’s “PBIS store,” open during lunch. Harris shared that their store has had multiple TTRPG-related items for “purchase:” dice sets, miniature figures, and even Hero Forge gift cards. Hero Forge is a digital platform where you can make a full color three-dimensional model of a TTRPG character for free. You can then pay to save and download its STL file for printing on your own 3D printer, or pay for Hero Forge to print and ship you the “mini.” It’s yet another subtle connection to the STEM focus at Western.

TTRPGs and Durable Skills

We can find some overlap in CASEL’s competencies with the closely related concept of “durable skills.” These skills may be called by many names: executive functioning, soft skills, hirable skills, 21st-century skills, “the 4 C’s.” I particularly like the phrase “durable skills” for implying that they are enduring competencies, and thus are necessary, lifelong habits of mind. For schools and districts across the United States, these competencies are often packaged as a “Profile of a Graduate” or “Portrait of a Learner.” (In 2023, NGLC published an extensive white paper that explored how such portraits are being put into practice, including Bullitt County, a Kentucky district.) These profiles or portraits often are created at a state level; as an example, Kentucky’s Portrait of a Learner was made not as a “mandate” but as “a powerful and voluntary strategy for building alignment across local communities and creating vibrant, future-ready learning experiences,” inspiring ground-up change instead of top-down compliancy. As we move into the 2026-2027 school year, these portraits will be essential as Kentucky launches a local accountability system of assessment where each district’s determination of how students are doing in such durable skills will be at least as important as an annual norm-referenced standardized test.

It is no stretch to say that TTRPG gameplay overlaps strongly with these profile/portrait competencies. In Kentucky’s Portrait of a Learner, the descriptive language of its “Creative Contributor” seems custom-made for Polyhedral Pedagogy as it asks students to “imagine and play.” Justin Gadd, the teacher whose use of TTRPGs was identified by KDE as a model for vibrant learning, referred to his district’s Profile of a Graduate when he was interviewed in a Kentucky Edition news segment from 2023: “You gotta be a Critical Thinker, you have to be an Effective Communicator, you have to be a Responsible Collaborator working with [your peers]. There’s math, there’s creative writing, there’s all kinds of skills that students can use.”

JCPS, Harris’ district, has its own Portrait of a Learner composed of “Journey to Success” skills: Prepared & Resilient Learner, Productive Collaborator, Emerging Innovator, Effective Communicator, and Globally & Culturally Competent Citizen. When I asked Harris, he was easily able to build a bridge between playing a TTRPG well and the integration of Journey to Success skills. Being able to effectively communicate and productively collaborate are the easiest to see in practice, and echoes what Justin Gadd said earlier; if players aren’t talking and working together well, their characters will not achieve a collective victory at the end of their adventure. When looking at the bulleted list of descriptors from the remaining Journey to Success skills, Harris further elaborated his connections:

Emerging Innovator: Takes appropriate risks and makes adjustments based on successes and failures. “The real teacher is failure. That's how you learn, right? I think that if they learn [failure while playing a TTRPG], they fail in that environment and then, because it's a safe environment where they can fail safely, they're not worried about it. Okay, they might get upset that their character got killed by the dragon, but they're not gonna be as upset. It’s not like getting an F on something, right? It's a safe space where they can fail safely and then come back from it.”

Prepared & Resilient Learner: Reflects on successes and challenges and makes appropriate adjustments in order to meet academic, personal, and professional goals. “You don't always succeed in D&D, right? [The students] have had encounters where they have failed or where they've been run off by a monster or they couldn't fight this particular monster because it was too powerful. So they come back to it and they figure out, okay, how are we going to do this? Or how are we going to solve this? I mean, so much of D&D is creative problem solving and working with each other. And sometimes it's recognizing when something is beyond you at this point . . . this is not the time for you to fight [the monster], but you're going to come back later and do it. And so you come up with a plan on how you're going to do it and how you're going to deal with it. And that very much teaches resilience.”

Globally & Culturally Competent Citizen: Demonstrates compassion and empathy for others. “Tabletop gaming is like theater, you know? And that we are playing characters, we're getting in the minds of characters. I mean, literally doing method acting. And so that by doing that, that helps build empathy. And by building empathy, then we end up looking at the world and other people in different ways. And so in a lot of ways, not only are they interacting with [other students in the class] from different classes, races, religions, gender backgrounds, different identities, but they're also learning to empathize.”

The authentic, vibrant learning that will be included in Kentucky’s local accountability system of assessment can truly tell the whole story of a student, whereas the percentage of correct answers the student got on an annual test is a few chapters at best. A novel approach is necessary when narrating a student’s life. And what better way to help tell the story of a student than to use the storytelling tool of TTRPGs?

Schools and districts with portraits or profiles often have some kind of “defense of learning,” usually at transition years (such as 5th, 8th, and 12th grade), where students use their own curated artifacts of learning to demonstrate mastery of their portrait’s competencies. Harris recalled a former D&D flex course student who used the TTRPG to thematically shape his own senior defense. “He did his defense as if it were a crime investigation. And the investigation was through his Journey to Success skills, right? But he did it all with this whole noir feel. And it was so good. Everyone who was on the committee was blown away. And it was one of the best things we'd ever seen.” Harris also expects his creative writing course to produce strong artifacts for future defenses, whether it be a student’s final draft of a short story, or pictures and video from one of their gaming sessions, or their character sheet as a dynamic avatar of their own journey of growth while in the class. The authentic, vibrant learning that will be included in Kentucky’s local accountability system of assessment can truly tell the whole story of a student, whereas the percentage of correct answers the student got on an annual test is a few chapters at best. A novel approach is necessary when narrating a student’s life. And what better way to help tell the story of a student than to use the storytelling tool of TTRPGs?

Taking Initiative with Polyhedral Pedagogy

Harris had the benefit of years of TTRPG experience before attempting his Full Infusion of Creative Writing with D&D. However, you don’t need to be a master of dungeons to try Polyhedral Pedagogy, nor do you have to begin with transforming an entire course. Instead, find a place to dip your toe, perhaps with an Elemental or Episodic Infusion.

Educator Sterling Harris

If infusing TTRPGs into your classroom still feels daunting, Harris recommends some pragmatic advice:

Don’t be afraid to start. Echoing the Nike slogan, just “definitely do it.”

Plan beforehand how you will group students. “Figure out early how you're going to deal with the numbers. If you're going to have a big class, how are you going to deal with that?” In a typical TTRPG play session, you usually have one DM/GM and four to six players. With the average classroom ratio of one adult to thirty students, it takes some clever ways to figure out how to leverage your resources and space. Harris eventually landed on the “three groups” rotation concept described earlier in the article. (In my book, I created a “Degree of TTRPG Facilitation” Framework that addresses this, along with examples of what others have done.)

Strong classroom management and relationships is the bedrock. Polyhedral Pedagogy is not recommended without first establishing routines and expectations, and if students don’t feel valued and trusted by you, they won’t feel comfortable taking the journey—but then again, this is true for any instructional approach to be successful. Take time to build your foundation, particularly in relationships: “I've always said that's what teaching is all about to me.”

Not all students may love to play TTRPGs on day one—but don’t let that stop you. “Some students are not going to be enthusiastic about it. And that's OK. Don't expect them all to be enthusiastic about it. And don't be turned off by it. But also, don't let that shut you down. You can find a way to work them in somehow.” Ask the unenthusiastic why they are reluctant, listen to their reasons, then find small entry points and low floor/high ceiling opportunities to get them to participate. You should also remember that very few of your instructional activities always have all students engaged all of the time, and that likely hasn’t stopped you from trying them. Do 100 percent of your students happily complete worksheets or take notes from a lecture? In fact, it may be an Infusion of a TTRPG that will get some of those students who don’t otherwise participate in your lessons to finally become active in your classroom.

Be willing to reveal your honest, vulnerable self to bring out the true selves of the students. Harris is not afraid to be a fun-loving geek in front of his class. “I'll be up there doing weird goblin voices and stuff like that, and they start laughing, and they realize that I'm going to be goofy, too. And so then they start doing it.”

What ultimately matters in Polyhedral Pedagogy is less about being a stickler for the game rules of D&D or any other particular TTRPG, and more about bringing vibrant learning into the classroom. As principal Melanie Santiago-Weaver reminds us, “We love seeing students involved in what truly excites and inspires them—because when students are passionate, that enthusiasm naturally carries over into their learning and school community. This is what we are all about at Western STEM Magnet High School. Our goal is to tap into our students' passions and interests through our magnet programs and Journey to Success experiences.”

Western High School, in all of its diversity, challenges, and assets, is a microcosm of so many schools across the globe. Many students in the world today feel unseen, apathetic, checked out. We have a diminished pipeline of rising teachers, and the current respect for public school educators in the U.S. may be at the lowest ebb. Many teachers are burnt out or are rapidly approaching their breaking point. However, the last thing we should do when we face such educational uphill battles is to reduce innovative approaches. Instead, it should amplify our urgency to inspire joy, not quell it; to connect with and ignite students’ passions, not ignore them; to rally behind teachers like Sterling Harris for combining evidence-based practices with evolutionary education.

We must invigorate our instruction with vibrant learning experiences that are revelatory and rigorous. Polyhedral Pedagogy offers a way to do both. In the parlance of TTRPGs, let’s roll for (and take!) initiative to transform teaching together and add all the modifiers we can.

Listen to Our Conversation on TTRPGs

While originally recorded as simply a means to generate a transcript and not to be published as a formal podcast, I found my debriefing interview with Sterling Harris after I observed his class to be a treasure trove of insights. With Harris’ consent to share, I’ve uploaded the full interview for anyone to hear those insights:

Credit for all photos: Adam Watson